“… Caspar Holstein was regarded in some circles as a wealthy Black businessman in a day when that was very rare, difficult and dangerous; in others as a tireless, politically engaged reformer and philanthropist; and others as a gangster, a racketeer. There is some truth to all of these images.”

~ Bill Kossler, journalist

Caspar Holstein was born on December 7, 1875 in Christiansted, St. Croix, Danish West Indies (presently known as the U.S. Virgin Islands). His paternal grandfather was a White, Danish officer of the Danish West Indies colonial military and his paternal grandmother was a Black woman of Africa. Their son, Caspar’s father, would become a landowner, making him well-to-do. Caspar’s mother, Emily, was a Black woman of the island country and would be his primary parent.

In 1877, when Caspar was only two years old, Mary Thomas led thousands of Black workers in a rebellion against Dutch colonialism. Although slavery had been abolished in 1848, Blacks continued to suffer hellish conditions. Thomas, known as Queen Mary, directed an insurrection which burned down Fredericksted and the entire western region of St. Croix. This event would forever impact Caspar, greater increasing his love for his people and island nation. Author Axel C. Hansen, in his From These Shores, detailed, “The harsh and inhumane treatment of the masses left an unforgettable imprint on the mind of young Caspar.”

In 1888, Emily and Caspar immigrated to New York City. Living in the Harlem community of the Manhattan borough, he attended elementary and secondary school in the Brooklyn borough, where he graduated from the Boys High School. After graduation, his mother passed away. Holstein attained work as a bellhop and in this position, he first learned the rules of gambling. In 1898, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was stationed on the U.S.S. Saratoga. Upon completing four and one-half years of service, he returned to New York City where he worked various jobs, including as a custodian, bellhop, doorman and, eventually, head messenger for a brokerage firm on Wall Street.

It was during this time that he became acquainted with the Chrystie family. In being asked to run an errand by Fannie, the wife of John, Caspar was given the wrong information. Using his resourcefulness, he was able to complete the errand. This impressed Fannie, who hired Caspar to read to the family’s grandmother, who was blind. He was later employed, most likely as a custodian, by John, a successful and wealthy bank on Wall Street. It was here where Holstein was introduced to the stock market.

During his time of working on Wall Street, Caspar Holstein began studying the stock market. He also mastered the principles of the “numbers” system, a victimless but illegal (as of 1901) lottery. Many Blacks of all socioeconomic status, but especially those impoverished, in New York City “played the numbers”.

The numbers game, traditionally, was a complex system based on lottery policy numbers in order to figure out the winning numbers. These twelve numbers were drawn from a pool of seventy-eight numbers. In Gangsters of Harlem, Ron Chepesiuk wrote, “In New York City, there was the so-called ‘New York number’, computed from the total pari-mutuel handles of the third, fifth and seventh races held at a particular track and the ‘Brooklyn number’, computed from the last three digits of the total pari-mutuel handle of the day. Once the numbers were drawn, the information was given to the bankers who collected money and made winning payouts.”

By the 1920s, the numbers game drastically changed. In The Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, Amy Carreiro explained, “No one knows for sure how this change came about. Some people speculate that it was a variation of a betting game in New England. Others give credit to Hispanic immigrants who played a similar type of numbers game. Still others credit Caspar Holstein, a West Indian.”

Merging concepts from both the stock market and the numbers systems, Holstein created his own private lottery that was similar to the Cuban lottery, bolita (Spanish for “little ball”). Utilizing various sources, including New York Stock Exchange daily shares, U.S. Customs House receipts and even pari-mutuel horserace betting, Holstein greater ensured a more equitable game.

The policy system that Holstein devised simplified the betting scheme and based the game, originally, on the daily closing of the New York Stock Exchange. Chepesiuk discussed this aspect of Holstein’s genius when he detailed, “The three-digit winning number was now selected as a combination of the last two digits of the ‘exchange total’ and a third digit from the last number of the ‘balances total’ … the beauty of the new system was that by having the numbers recorded daily in the newspaper, the game could not be fixed.”

His modification comforted players who worried that the game was rigged to never have a winner to pay. In his lottery, a player would select a three-number combination. When a number “dropped”, Holstein paid out six-hundred to one. However, the actual odds of any number being selected as a winner, according to Bill Kossler in his “Black History Spotlight: Caspar Holstein” for The St. Thomas Source, “were 999 to one. So, he raked in a steady profit and became a wealthy man, called the ‘Bolito King’ or ‘Policy King’ by newspapers.”

Known by many in the New York Underworld as “The Bolito King” by 1920, Caspar Holstein, and numbers queen, Stephanie St. Clair, had revived the gambling systems that had been absent since the conviction of Peter H. Matthews eight years prior. Holstein earned his wealth through the policy system. However, his gambling services were like those of his immigrant mob counterparts, including Italian, Irish and Jewish, in New York City.

By the mid-1920s, it’s believed that Caspar Holstein’s income, at his peak, was $12,000 (approximately $175, 000 USD) per day. The wealth he earned from his lottery has been estimated to have been greater than $2 million USD (approximately $29 million USD in 2019). Holstein lived a lavish life, owning three of the best apartment buildings in his beloved Harlem community, a mansion in Long Island, a collection of luxury vehicles and several acres of farmland in Virginia. From his opulent residence on 138th Street, near Lenox Avenue, he was always chauffeured in a Lincoln sedan.

Caspar Holstein’s appearance, significantly, his style, was a display of refined wealth. His attire was custom and he was always well-groomed. In Harlem’s Danish American West Indies, 1899-1964 by Geraldo Guirty, the journalist described the “Numbers King” as “Beau Brummell, always fashionably, yet conservatively dressed in tailored suits. Irish linen was his favorite fabric. He wore a fedora and Florsheim shoes, and sometimes used a walking cane. He was a bachelor and wined and dined senators, congressmen and Virgin Islands leaders in his luxury apartment.” Holstein, who was not a womanizer, neither drank or smoked.

(No copyright infringement intended).

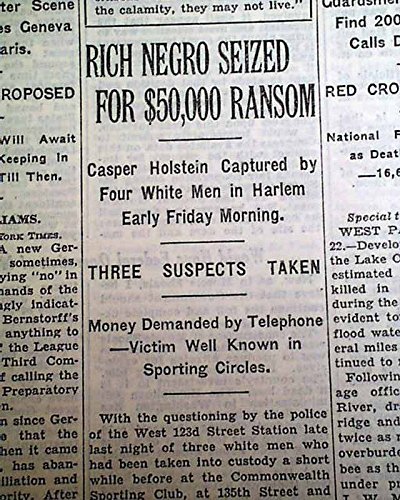

In 1928, Holstein was kidnapped and beaten by five White men who demanded $30,000 in ransom. Three days later, he was released and insisted that the ransom was not paid. In other accounts, the ransom amount was stated to have been $50,000 and some still, reported that the ransom was actually paid the next day. Regardless of the amounts and days, Holstein, who could identify the men, refused to for business reasons. However, the five men, Michael Bernstein, Peter Donahue, Anthony Dagostino, Moe “Monkey” Shubert and Rudolph Brown, who had been arrested were charged with the kidnapping of Holstein.

Whatever actually occurred to Caspar Holstein in this terrifying incident, what is for certain is that his kidnapping and accompanying ransom amount made the news, including The New York Times. They captured the attention of White mob figures and corrupt city officials. These people sought to take over Harlem because they discovered that “n*gger pennies” were adding up to great wealth in the Black community.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1932, J. Richard “Dixie” Davis, an attorney for Blacks involved in the New York policy systems, sought to take over the Harlem numbers organizations, including that of Caspar Holstein. Assisting Davis was mobster Arthur Flegenheimer, popularly known as “Dutch Schultz”. They expressly viewed the takeover of Harlem as extremely lucrative, especially as Prohibition was in the process of being repealed. However, Schultz took on a leading role, utilizing violence and murder as well being aided by other corrupt officials of law who arrested and/or prosecuted his competition.

Davis and Schultz faced resistance from St. Clair, aided by Harlem mob boss, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson but Caspar Holstein was primarily forced out of business. Schultz would be murdered by his fellow mobsters, led by Salvatore “Charles ‘Lucky Luciano’” Luciana in 1935. That same year, Holstein, who had scaled back his operation, was arrested for gambling. He maintained throughout the trial and his incarceration that he owned the building, The Turf Club, but not the gambling operation within. The social club, where Harlemites of all classes met, was located at 111 West 136th Street. The building, according to Kossler, was the “… single leading organization in Harlem. The Turf Club occupied a five-story, elaborately equipped brownstone building, decorated with vivid horse-racing prints, photos of major jockeys and shined brass bits. Most wealthy Black New Yorkers were members of the club in its day.”

Holstein was convicted for illegal gambling in 1936 and served less than a year of jail. He continued to decry law enforcement for repeated harassment and false arrests without cause. Upon his release, he retired from gambling but continued actively supporting the Black community within America and of his home country, which was by this time known as the U.S. Virgin Islands. This support began in the early 1920s and lasted for the remainder of Holstein’s life. In “Holstein Set Free by Abductors,” printed by The New York Times in 1928, Caspar Holstein was described as “Harlem’s favorite hero, because of his wealth, his sporting proclivities and his philanthropies among the people of his race.”

Caspar Holstein used his wealth to support various persons, organizations and institutions. A patron key to the Harlem Renaissance, he donated to the needy and to charitable organizations. He faithfully believed in the creative genius of Black people and showed it. According to historian David Levering, Caspar Holstein was one of the six most important benefactors of the Harlem Renaissance. According to Chepesiuk, Langston Hughes, writer extraordinaire of this explosively creative period of Black arts, politics and social mobility, claimed that Holstein actually “had ‘mid-wifed’ the so-called New Negro Literature.”

Holstein helped finance the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) founded by Marcus M. Garvey of Jamaica. He even purchased Liberty Hall, the headquarters of the UNIA, permitting it to operate until it disbanded after the deportation of Garvey. Holstein then developed the hall into a residential building, which he named Holstein Court, for Black business owners and professionals.

In the article Kossler wrote, he detailed diverse ways of Holstein’s philanthropy. The writer touted, “He supported students, helping with tuition, letters of recommendation and the like. In an effort to foster creative literary expression among Black writers, he created an annual Holstein writing prize through the Urban League’s magazine, Opportunity, which awarded $1,000 to the winner. He built dormitories at Black colleges, supported a Baptist school in Liberia and funded a home for delinquent girls in India and gave to Howard and Fisk universities. Holstein founded the Monarch Lodge No. 45 of the International Benevolent Order of Elks in 1907, and ran the mutual-aid society for decades.”

The Chrystie family, who had assisted him when he was a young man and with whom he shared a kindred connection, also benefitted. When they lost their family fortune in the Stock Market Crash of 1929, Holstein supported John and Fannie. Chepesiuk revealed that Holstein’s generosity to the Chrystie family was immense, as he paid “for their apartment on West 93rd Street from 1921 to 1933 and ensuring they maintained the quality of life to which they were accustomed. When the Chrysties died, the Numbers King paid for their funeral expenses.”

Though Holstein, as a young boy, moved to the States, he, as an adult, remained deeply involved with his home country. In 1917, the United States purchased the Dutch West Indies for $125 million (approximately $2,625 billion USD in 2019) and renamed it the “U.S. Virgin Islands”. Because World War I was impending, America assigned the U.S. Navy to administer governance of the island. When Holstein visited, what he experienced was alarming; he felt the islanders were treated like slaves on a plantation. Hansen explained the negative treatment, writing “Many of the naval and civilian officials were White Americans from the southern part of the United States, who brought with them the rural prejudices of the region.”

Caspar Holstein became militant in his activism to better the conditions of his people. He served as the president of the New York branch of the Virgin Island Association. He spent many thousands of dollars, as Chepesiuk reported, “… on political consultants in Washington, D.C. to lobby the Virgin Islands case on Capitol Hill to congressmen, senators and bureaucrats. To promote the cause, he spent $3,000 to buy a full-page ad in the Washington Post.”

Holstein was highly active in raising funds to support the island. This was significant, especially regarding relief from natural disasters, such as the hurricanes that devastated the country in 1924 and 1928. He set up a relief fund of $100,000 (approximately $1, 500,000 USD in 2019) for the hurricane of 1924 and Holstein even chartered a vessel to have supplies delivered to his native country for the one that struck four years later. He spent more than a quarter million dollars purchasing land in St. Croix, primarily on the South Shore.

Aside from promoting education, brotherhood and civic service, Holstein was integral to political and nationalist activities in his homeland. In 1920, he joined the Virgin Island Congressional Council. Founded by Anselmo Jackson, Holstein later served as the president of the organization. He was outspoken, verbally and in essays printed by publications such as Negro World, Opportunity and the Washington Post, demanding for the removal of the naval regime installed by the United States to govern. Caspar Holstein, who pushed for self-determination and civilian rule, was successful in leading the campaign for the termination of naval rule in the Virgin Islands. Holstein’s triumphs occurred in 1927, when Virgin Islanders, domestically and internationally, became citizens. In 1931, the United States appointed the first civilian governor of the Virgin Islands.

For the remainder of his life, he continued to support the Black community, Harlem and the Virgin Islands. After being ill for two years, Caspar Holstein died at the home of his good friends, Mr. and Mrs. Alverstone Smothergill, in Harlem on April 19, 1944; he was sixty-seven years old. His funeral service on April 24th drew hundreds who came to pay their respects to the brilliant policy systems giant, astute businessman, generous philanthropist, dedicated Virgin Island nationalist and committed patron to the Harlem Renaissance.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In his memory, there are various tributes, including a housing community in his home country and a scholarship named in his honor at the University of Virgin Islands. In recent years, there has been renewed interest in Caspar Holstein due to films, including Hoodlum, and television series, such as BET’s American Gangster, about Black figures in organized crime. On Boardwalk Empire of HBO, it has been stated by actor Jeffrey Wright that his character, Dr. Valentin Narcisse, was inspired by Caspar Holstein. Winner of an Emmy Award and a Tony Award, Wright garnered high praise for his role in Season 4 and 5 of the critically-acclaimed series.

This image was sourced from Pinterest.

(No copyright infringement intended).

“We cannot enjoy half slavery and half freedom. We want it all or nothing.

… We want to be the same as every member of this American nation, and we are entitled to that privilege. I am told you cannot oppose government, but, by God, government can hear us cry, and must hear us protest and we are going to protest until we get the form of government we wish.”

~ Caspar Holstein