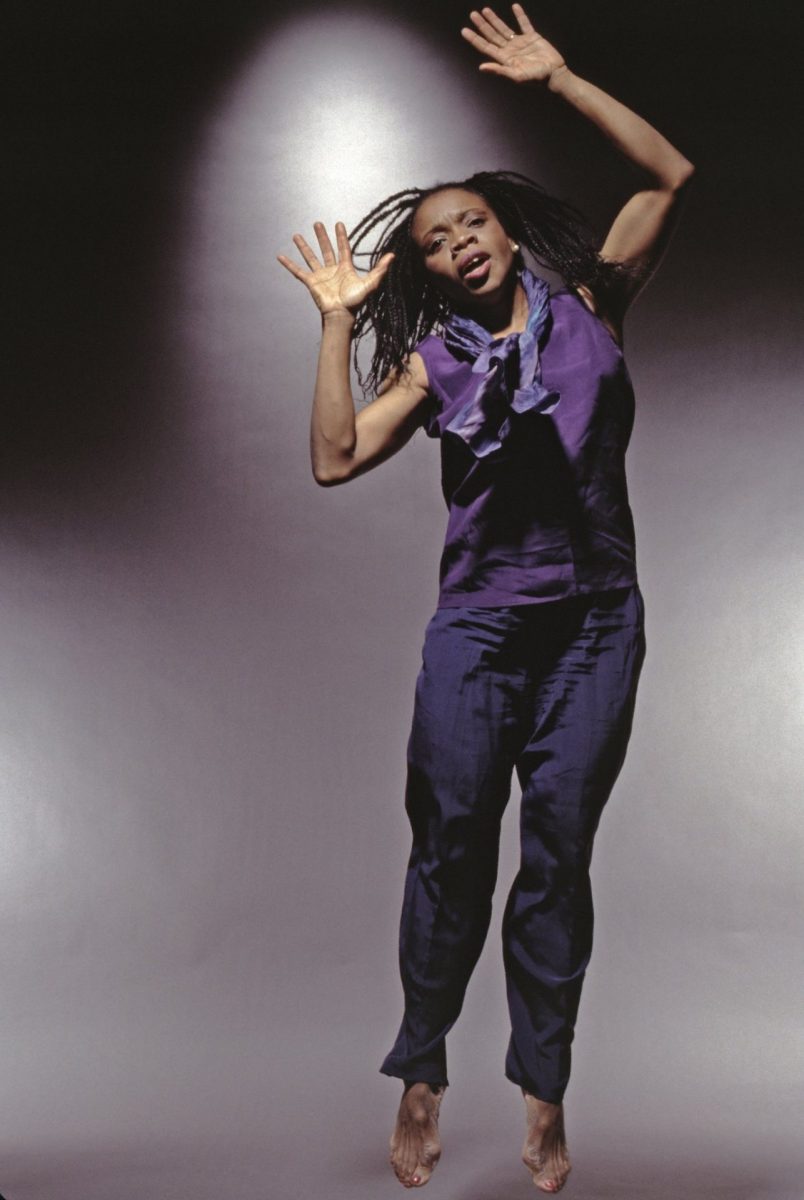

“Her deep humanism informed workshops she crafted to help dancers and non-dancers alike feel more whole, more connected with themselves and each other. As a performer, she was an electric presence and a beautiful mover. As a choreographer she broke through expected norms to find her own unique original form.”

~ Joan Finkelstein, director of Harkness Foundation for Dance

A baby girl was born on October 27, 1944 in Florence, South Carolina to Roscoe and Oralee (née Williams) Cummings. The oldest of what would be their three daughters, the new parents named her “Blondell”. Their life in the South held little promise, as the Cummings parents labored as sharecroppers, picking cotton and tobacco for a living. Desiring more, especially for their new family, they moved to New York City. The Cummings settled in the Harlem community of the Manhattan borough when Blondell was still an infant.

Both Oralee and Roscoe worked to support their family, which soon included Hilda and Gaynell. Oralee worked as a domestic and later as a nurse while Roscoe drove a taxicab. By the time, Blondell was a teenager, the Cummings moved to live in the borough of Queens. A bright and creative girl, Blondell performed well in school. She would ultimately earn a Bachelor of Arts degree in Dance and Education from New York University and a Master of Arts degree in Fine Arts from Lehman College of City University of New York. Additionally, she studied at the dance schools of Alvin Ailey, Martha Graham and José Limón.

Highly passionate about film and photography, which were key to her studies at Lehman, Cummings created the Video Exchange, an organization to document dance practices and performances. Concurrently, she began dancing professionally with companies such as those of Rod Rogers and Kai Takei as well as the New York Chamber Dance Company and the New Jersey Repertory Company.

In 1969, she was a founding member of Meredith Monk’s company, The House. It was at The House where Cummings received great praise. In her biographical essay at THIRTEEN: Media with an Impact website, writer Thomas F. DeFrantz championed “her virtuosic abilities to project character through gestures and sounds, most notably as the Dictator in Monk’s QUARRY (1976).”

Blondell Cummings created the Cycle Arts Foundation in 1978. The purpose of this multi-disciplinary arts collective, that was centered upon familial issues, relationship development and creation of the arts, was to uplift and empower.

As a dancer and choreographer, she worked for the next several decades in works such as Monk’s opera, Education of the Girlchild (1973); Yvonne Rainer’s film, Kristina Talking Pictures (1976); and Joanne Akalaitis’ The Photographer/Far From the Truth (1983). In the latter, she incorporated a stuttering pace of movement that alternated between restraint and explosion, à la stop action film, that appeared inspired by her passion in photography.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Cummings multi-media work was presented as an individual artist and in collaboration with others. Her pieces included The Ladies and Me (1979), considered, as DeFrantz wrote, “a ‘visual diary’ set to the music of Ma Rainey, Billie Holiday, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Mary Lou Williams, Ella Fitzgerald and others … and For J.B. (1990), dedicated to Josephine Baker.” Her work also contains 100% Cotton Natural Fiber, which features the music of Oumou Sangaré of Mali and 3B49. Performed by two dancers, Cummings choreographed this piece that was based upon the tragic murder of her father by one of his passengers. A theme pervasive in this work is the isolationist aspect experienced by many taxi drivers.

Blondell Cummings is perhaps most famous for her groundbreaking work, Chicken Soup (1981). In it, she portrays a woman who is working in her kitchen. Its creation was inspired by her time as a little girl in her grandmother’s kitchen. She included her unique vocalizations and dance rhythms as well as opportunities for the audience to participate.

Inclusion of music by Monk, Brian Eno and Brian Walcott as well as the reading of a chicken soup recipe, Chicken Soup was intended to show the simplicity yet complex nuances of the lives of women at home. In a 2007 The New York Times interview, Cummings shared, “There was no fast food … Food took a lot of time to make. We spent more time in the kitchen. We ate there. Kids played and helped out in the kitchen. The mothers would get together in the kitchen and talk about life and their families. They’d look out the window and make comments about what was going on outside.”

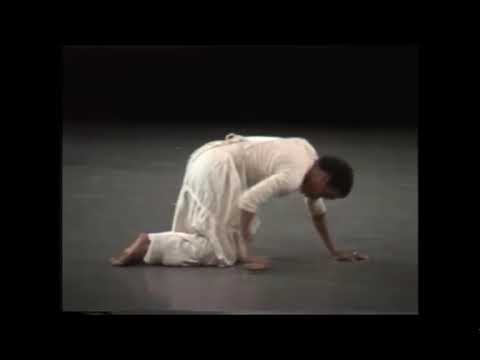

Becoming a hit, it was acclaimed by many critics. In The New Yorker, writer Joan Acocella put forth in her review that “ … Blondell Cummings made a dance, Chicken Soup, in which, while scrubbing a floor on her hands and knees — an act of exemplary realism — she would repeatedly break off, rear up, and shake, in jagged, convulsive movements, as if she were in a strobe light. Then, with no acknowledgement of this interruption, she would go back, serenely, to scrubbing the floor. This strange back and forth made the piece very interesting psychologically: the floor-scrubbing so homey and soapy and nice (Cummings wore a white dress), the convulsions so violent and weird. Was this woman happy, doing this domestic task, or did she hate it so much that she was going crazy? Then there was just the formal interest: the texture, the tension.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 2006, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) designated Chicken Soup an American masterpiece. It also has inspired many, including the Urban Bush Women dance company. Because of its designation by the NEA, this contemporary dance company was able to re-formulate Chicken Soup for their own interpretation to present. Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, artistic director of Urban Bush Women, shared the immense influence that Blondell Cummings had on her in the article, “Remembering Blondell Cummings (1944-2011) of Dance Magazine, by Wendy Perron. Zollar reflected that, “Blondell and Dianne McIntyre were the first African American women I saw doing experimental work rooted in a Black experience and identity. They were pushing the form. It gave me courage, a possibility to see ways of creating and thinking and doing that I hadn’t seen.”

Giving tribute to one of her inspirations, Zollar invited Cummings to teach Chicken Soup to members of Urban Bush Women in honor of the company’s 20th anniversary. Her reasoning was to pass on the powerful sentiment of this work; the rich legacy of Cummings; and the brilliant creativity of those, especially Black women, in the field of dance to the next generation of dancers.

One of these dancers was Marjani Forté, founder of her own collective, Love/Forté. As she shared in the Dance Magazine essay, “Chicken Soup was score building, a kind of improvisation that I realized later I would be doing the rest of my career with my collective Love/Forté. It was the first time I was performing and reflecting on my lineage — learning how to braid hair with my mom, snapping peas or catching fish. There’s a moment on the rocking chair with a stream of gestures that are coming from things that happen in the kitchen. It was a profound experience I could only understand in hindsight. I am currently doing conjuring-based improvisation, creating or recreating an environment and expression. In Chicken Soup, it was frying chicken or making cornbread in a cast iron skillet. Acting doesn’t work; you have to be invoking the memory … She (Blondell) supported all of my work.”

Blondell Cummings’ collaborations include Ishmael Houston-Jones for Parallels (1982); Jessica Hagedorn on The Art of War/Nine Situations (1984); and Tom Thayer in Omadele and Giuseppe (1991). She also worked with Junko Kikuchi to put on Women in the Dunes (1995), which is sourced from the 1962 novel, The Woman in the Dunes, by Kobo Abe.

Residing in New York City, Cummings performed at venues such as Danspace, The Kitchen and The Joyce Theater, as well as abroad in Asia and Africa. In her article, Perron wrote of her and the dancer/choreographer attending Bill T. Jones’ musical, Fela! Cummings casually mentioned her meeting the famous Nigerian musician and activist at The Shrine, a nightclub in Lagos, during one of her visits to Africa.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Extending her outreach, Blondell Cummings also taught at the Lincoln Center Institute and institutions of higher learning. These included Ivy League member, Cornell University, and her alma mater, New York University

On August 30, 2015, Blondell Cummings passed away in her Manhattan home. Suffering from pancreatic cancer, she was seventy years old.

Her accolades and honors were many. They included her being active for many years as a member of the Selection Committee for the New York Dance and Performance (“Bessie”) Awards. Cummings was the recipient of awards from organizations such as The New York Foundation for the Arts as well as Guggenheim and Robert Rauschenberg Fellowships.

Blondell Cummings has also been profiled in the 1988 documentary, Retracing Steps: American Dance Since Postmodernism. She also was highlighted in the 2001 PBS three-part series, Free to Dance. This docu-series profiled African-American choreographers and their pivotal role in the development of modern dance in the United States.

I don’t think of myself as being avant-garde; I think of myself working in a time in history in which that is what’s going on and I’m certainly affected by it. There’s a climate that allows me to exist within it.~ Blondell Cummings