“(The works of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson) is ‘Homeric in content, quantity, and scale.’”

~ James M. Manheim, The MacArthur Foundation

On February 18, 1940, a baby girl was born in Columbus, Ohio to Leroy and Helen (née Zimmerman) Robinson; they named her Brenda Lynn. That same year, her family moved to Poindexter Village, a new community that was one of the first housing development projects in the United States to be federally-funded. Poindexter Village was constructed where Blackberry Patch, a semi-rural community historically populated by African-Americans, had been located. Both communities were close-knit and their progress and success were contingent upon familial relationships, whether blood, fictive kin or communal.

Life in Blackberry Patch and, later, Poindexter Village were replete with Black cultural traditions such as storytelling, reverence for elders and promotion of creativity, and these greatly inspired Brenda. She loved to be around her family and in a video interview at her website, Aminah’s World, she recalled how her father had her learn from her elders. One elder in particular, was her great-aunt Cordelia; affectionately known as “Big Annie” which could be a Black language slang for “Big Auntie” or great-aunt.

To a young Brenda, she was especially pivotal in recounting their family’s history. Born in Georgia, Big Annie, who had been enslaved, recalled the history of their loved ones who survived the Middle Passage and life under the cruel and oppressive system of slavery. She also shared vivid stories of life in Blackberry Patch, which included vibrant persons such as The Crowman and The Chickenfoot Woman. All these themes would powerfully inform and impact Brenda for the rest of her life.

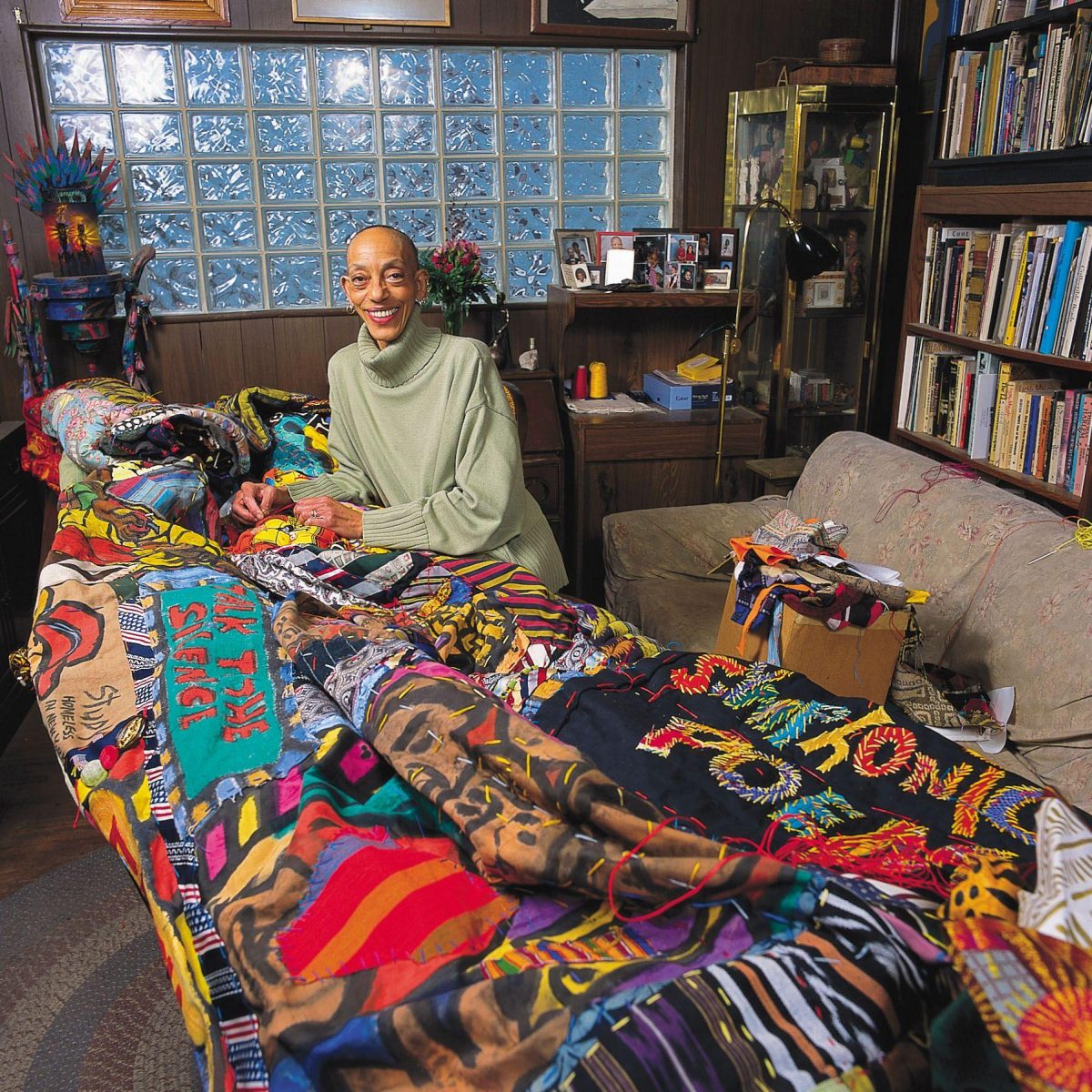

Although her father worked as a custodian in a local school and her mother managed their family as a homemaker, both were artists. From an early age, Brenda was passionate about art and her parents strongly encouraged her interests. From her mother, she learned how to sew, weave and master seamstress skills, working with buttons, fabric, needlepoint, ribbons and yarn. From her father, she learned to work with raw materials and scraps of items, ranging from charcoal, glass, leather and seashells to animal hides, clay, rope and wood. Brenda also worked with a concoction of brick dust, glue, lime, mud, pig grease, red clay and sticks that her father taught her how to make; they called this creation “hogmawg” and it was used to develop two-dimensional and three-dimensional pieces. On her website, Aminah’s World, she stated, “I began drawing at the age of three. My father would give me wood to paint on and paint in little enamel tins. My studio was under my bed … I never had any doubt in my mind about being an artist.”

Reared in a structured and Catholicism practicing household, Brenda was an independent spirit. In an August 1, 2003 interview with the Cincinnati Enquirer, Robinson affirmed, “It didn’t matter how many spankings or Hail Marys I got”, and she often snuck away from her home in order to take art lessons at the nearby Beatty Park Recreation Center. Always armed with a sketchbook, she, at only eight years old, had a first solo “exhibition” at a church revival; it was a series of her drawings strung to hang on a clothesline.

(No copyright infringment intended).

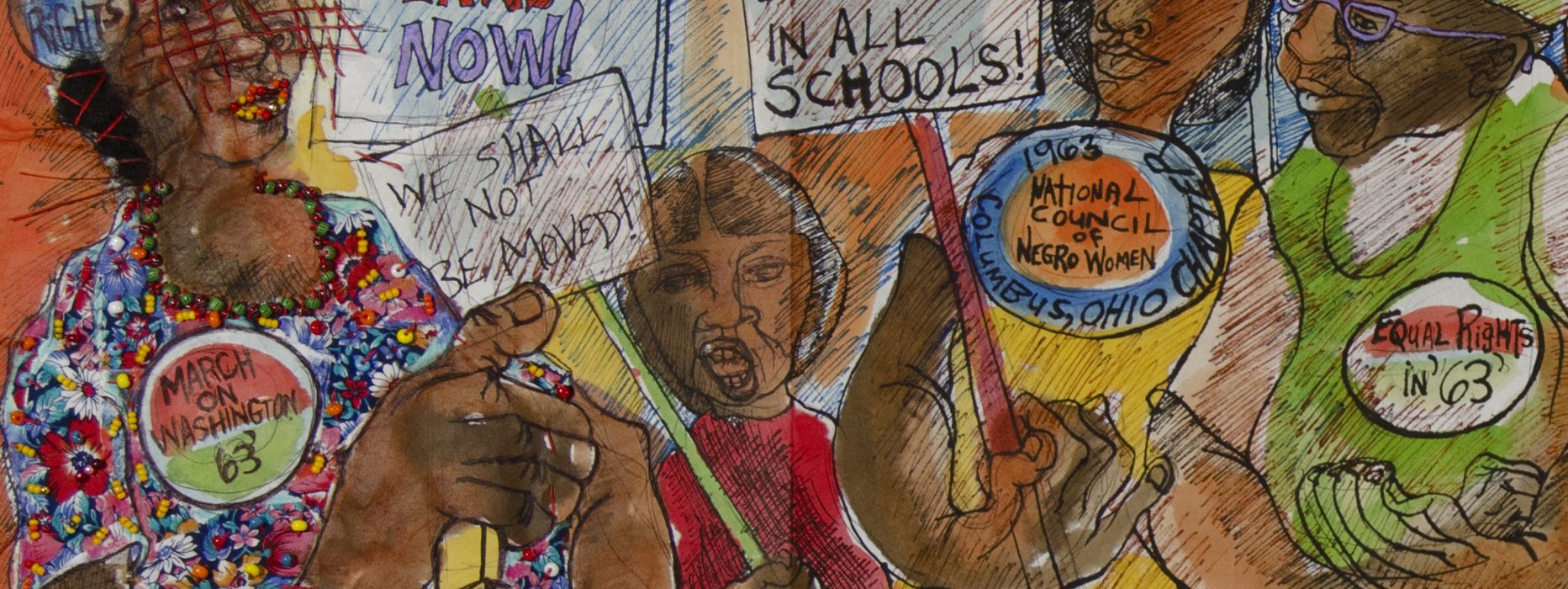

Brenda Lynn Robinson continued to create and upon graduating from East High School in Columbus, she attended, from 1956 to 1960, the Columbus Art School, presently known as the Columbus College of Art and Design. In 1958, she gained a position at the Columbus Public Library, where she created illustrations and devoured content about Africa Diaspora culture. As a young adult, Robinson was active in the civil rights movement and participated at the March on Washington in 1963. Her participation at that event would later inspire her art piece, Unwritten Love Letter: March on Washington (1989).

In 1964, Brenda married Clarence Robinson, a serviceman in the U.S. Air Force. Because of his enlistment, she traveled with him and lived on several air bases within the Unites States, including in Idaho and Mississippi. She worked in various places of employment, including at a television studio. In 1967, the Robinsons welcomed the birth of their only child, Sydney Edward, who was born in Biloxi.

While she would later take courses from Ohio State University, Franklin University and Bliss College, she believed in the expertise of those outside formal institutions of arts education. One of these experts was Elijah Pierce, who she met in 1968 and later became a mentor of hers. A barber, his artistic woodcarvings were displayed in his shop. On her site, she reveres Pierce, praising, “Elijah Pierce was my spiritual mentor and friend. He was a great person, a great artist and a person who walked with integrity, and passed on so much of that wisdom to me … We just generally like to be around each other. There was just a connection there.” In the “Sunday Magazine” of the October 31, 2004 edition of Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Robinson shared that Pierce guided her in experiencing the world by utilizing her “four ears … the heart, soul, ‘illuminations’ and ancestors.”

In 1971, the Robinson marriage ended and Brenda, with Sydney, returned to Columbus, Ohio. From 1971 to 1990, she worked as an art instructor with Columbus Recreation and Parks Department. She taught art, even puppetry and spinning on a wheel, at Beatty Park Recreation Center, the same local community center where she snuck to in order to learn art as a young child.

Though she created art during her marriage, she entered a new phase of development in her art. Sadly, her creations came at a cost, much greater than the periods of severe economic struggle she suffered in order to support herself and her son. In the Enquirer story, Robinson shared that, though Sydney inherited her creativity, he elected to enter the field of engineering because he saw it as more economically stable. She felt that because he was not expressing his creativity, “he became very depressed”. Tragically, Sydney committed suicide in 1994; he was only twenty-seven years old.

In 1974, she bought a house in which she and Sydney lived and at this time, she began creating one of her most famous pieces, Gift of Love, a chair that is eclectic in artistic design. On her site, Robinson stated about this work, “I started this chair in 1974. I was trying to find furniture for the house. So, I said, ‘I need to build a chair.’ I didn’t really have the materials, so my father and friends gave me scraps … It represents my family and community. That’s what the chair is about – life in Columbus.” Though she never considered a piece as “finished”, it was “resolved” in 2002 and it’s a promised gift to the Columbus Museum of Art. In order to exhibit it, a wall had to be removed from her home. Robinson agreed to its removal but only on the condition that a new wooden door, on which she could carve, be installed.

(No copyright infringment intended).

Brenda Lynn Robinson’s intricate, complicated and engaging works of art began to draw attention throughout Columbus and in 1979, she was awarded a grant from the Ohio Arts Council. From the Forum for International Study, she was awarded a travel-study fellowship. She traveled to different sites in Africa to gather primary research on Africans who were forced to undergo the treacherous Middle Passage and suffer slavery in the Americas. While in Africa, she met an Egyptian cleric who gifted her with the name of “Aminah”, which is Arabic for “faithful” or “trustworthy”. Aminah is a derivative of the name, “Aamina”, who was the mother of Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. Upon her return to the States, she legally included Aminah as her forename.

Over the next several decades, Robinson traveled to better educate herself in creating her art, developed thousands of works and illustrated books. It was only natural that she would compose her own books. In 1983, she visited Sapelo, Georgia to research her own ancestors who had been enslaved before and during The Civil War. Her research led her to observe, as per her site, “Sapelo, Georgia is off the coast of Savannah, Georgia and it takes twenty minutes to cross over on the Sapelo ferry. In the early 1800s, it was owned by Thomas Spalding. He would go to the auction block in South Carolina, purchase a lot of slaves, and bring them back to Sapelo to work the cotton and sugar cane fields.” In 1983, she also participated in her first group exhibition at the Carl Solway Gallery in Cincinnati, Ohio.

The following year, Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson had a one-woman exhibition in Chicago, Illinois at Esther Saks Gallery. This led to her greater involvement in exhibitions held in museums, including, as per her biography page at Encyclopedia.com “ … at the Akron Art Museum (1987 and 1988), the Columbus Museum of Art (1990), the National Museum for Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. (also 1990), and various colleges and university art galleries. As her fame grew, she sold some works, if she approved of the buyer; they commanded prices of up to $20,000 apiece.”

In 1989, several commendations, including the Governor’s Award for Visual Arts from the Ohio Arts Council, were awarded to Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson. That same year, she won a grant from the Ohio Arts Council for a residency at PS 1 school in the Queens borough of New York City and was also given a Minority Artist Fellowship. This fellowship, awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, allowed her to work with Robert Blackburn at the Printmaking Workshop, also in New York City.

(No copyright infringement intended).

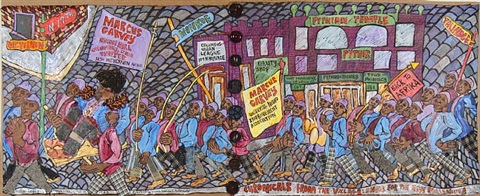

Designing large and gargantuan mixed-media pieces of narrative art often took Robinson years, even decades, to construct. The sizes, which could be a couple hundred feet in length, and materials, such as fabric and music boxes, were diverse. She referenced these pieces as Button Beaded Music Box RagGonNon Pop-Up Books. Abbreviated to simply “RagGonNon”, the term, according to the article featured in the Columbus Dispatch, means “… it’s made of rag and it’s gone – into the future!”

In 1990, the Columbus Metropolitan Library commissioned Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson to create 40-foot panels that illustrate historic African-American neighborhoods within the city. This vividly-hued, intricate masterpiece, called Life in Sellsville (1871-1900) and Life in the Blackberry Patch (1900-1931), even contained actual addresses and names of residents. Its creation took two years, debuting in 1992, and it was this commission by Columbus Metropolitan Library that allowed her to create art full-time. In 1992, Robinson participated in the group exhibition, Will/Power, held at the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University.

That same year, she also authored and illustrated The Teachings: Drawn from African-American Spirituals, which was her first book published by a mainstream publishing house, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Of this book, Robinson divulged on Aminah’s World, that, “The spirituals speak of survival, of freedom and determination, of love and faith, of justice and hope. The spirituals weaving together the memories that carry us into the future, must not be forgotten. They are our stories, our chants, our dreams, our lives. As they did so long ago, they continue to reach out and offer hope.” Robinson continued to author and illustrate her own books. She also illustrated other authors’ children’s books, including To Be a Drum authored by Evelyn Coleman and Elijah’s Angel: A Story for Chanukah and Christmas written by Michael J. Rosen; the latter won the National Jewish Book Award in 1993.

In 1997, she had her first exhibition at Hammond Harkins Gallery in Columbus. The following year, Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, with Susan Saxbe, her agent, and Wayne Lawson, director of the Ohio Arts Council, visited Herzliya, Israel. The artist was there on a residency supported by the Ohio Arts Council. Robinson felt that the three major religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, practiced in the area were sacred, rendering her regard for humanity even more profound. In her forthcoming pieces, she would use materials that had been given to her by those she met in Israel.

In 2002, two major events happened. One was the award of an honorary doctorate of fine arts from Ohio Dominican University. The other was the premier of the exhibit, Symphonic Poem: The Art of Aminah Robinson, at the Columbus Museum of Art. This retrospective work encompasses the trials and triumphs of Robinson’s life and art and integral to this exhibit is the tapestry, Journeys. She began constructing this multi-paneled piece in 1968 and it contains images of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr as well as the victims of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

The exhibit, sponsored by the Columbus Museum of Art, toured the United States throughout the mid-2000s and showed at the Brooklyn Art Museum, Tacoma Art Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art. According to author Ramona Austin in “History, Myth, and Memory: Africa in the Art of Aminah Robinson” of Symphonic Poem, the exhibit contains “memory maps”. These maps, or multi-media constructions of appliquéd cloth panels, feature “… the idea and symbols of Africa – as a reservoir of culture, as the abode of spirits and inspiration for form and meanings that have traversed the great Trans-Atlantic African Diaspora to the Americas.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 2003, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati commissioned Robinson to create two enormous RagGonNon pieces. Her books were also prepared for show at the Art Institute of Chicago. The following year, she was awarded another grant to travel to Santiago, Chile. In the capital city, she, as an artist-in-residence program at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, would have a solo exhibition.

In autumn of that same year, 2004, Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson was awarded the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation! This award, as stated on the foundation’s website, is given for “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction.” As a MacArthur Fellow, she was gifted a $500, 000 stipend whose purpose is to stimulate new creative activity.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson continued to create, whether it was in her home, which contained books, art materials and mosaic tiled floors that contained the baby teeth of Sydney or in her art studio in back of her house. Her work was featured in exhibitions, including a solo exhibition at ACA Gallery in New York City, and commissioned by the Baker Center at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. Throughout her life, she would contribute incredible works of art to show in more than two-hundred exhibitions.

(No copyright infringement intended).

One of her last works was the collection, Aminah’s Presidential Suite, which premiered at the Columbus Museum of Art. Given the vision by God to create this series, Robinson honored the election of President Barack H. Obama. According to the statement by the museum’s curator-at-large, Carole M. Genshaft, Aminah’s Presidential Suite, “embodies the hopefulness in the hearts of Americans, who like Aminah, were proud to witness the election of the country’s first African-American president.” The series includes the pieces Bo Walking the First Family through the Rose Garden; Detail of Wings of Our Ancestors: The Slaves Who Labored and Built the Nation’s Capital in Washington DC, 1783-During the Civil War; and South Carolina Cotton Picker I.

This moving series by Robinson, as Genshaft detailed, “… focuses on the far-flung communities – Hawaii, Indonesia, Kenya, South Carolina — that have merged to produce President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. The subject matter of this work spans generations and links neighborhoods all over the world. The work reflects Aminah’s profound joy in the election of the nation’s first African-American president and, at the same time, her guarded hopefulness that by remembering the injustices of the past, they will not be repeated in the future.”

On May 22, 2015, Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson passed away from heart complications; she was seventy-five years old. Her awesome work as a visual artist, storyteller and educator magnificently represented the African Diaspora, significantly African-American, culture that she truly respected, admired and loved. A devoted believer in the Asante principle of Sankofa, her extensive work and legacy illustrate the immense value of honoring the past to positively progress forward.

“… and so, even though our ancestors guide us, keep us, they also give us voice so that we can pass it on … and I guess that is the purpose of my work … simply, to pass it on.”

~ Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson