“At a time when there were few high-profile Black athletes beyond Jackie Robinson and Joe Louis, Coachman became a pioneer. She led the way for female African-American Olympic track stars like Wilma Rudolph, Evelyn Ashford, Florence Griffith Joyner and Jackie Joyner-Kersee.”

~ Richard Goldstein, writer, The New York Times

On November 9, 1923 in Albany, Georgia, a baby girl was born to Fred and Evelyn Coachman. The fifth of what would be their ten children, Alice grew into a youth who truly enjoyed sports. Although she excelled in basketball, she was stellar in track and field. Unfortunately, she had three strikes going against her: gender, lack of familial support and segregation. Because public facilities outlawed integration, Alice was barred from being able to train and participate in her athletic endeavors such as softball, baseball and, notably, track.

Undeterred, she developed a type of guerilla training regime, including the use of rope and sticks to simulate a high jump crossbar. What was truly unique was that she ran barefoot on the winding, red dirt roads of Albany.

In 1938, Alice Coachman was enrolled at Monroe Street Elementary School. Despite the hesitation of Fred and Evelyn, she joined the track team, encouraged by both her aunt, Carrie Spry, and teacher, Cora Bailey. Coached by Harry E. Lash, she quickly gained a reputation for her excellence and was recruited by esteemed institutions and universities. In the Amateur Athlete Union (AAU), Coachman was exceptional! She slayed her competition in its national championships for track and field. Alice’s dedication, supported by these key individuals, soon allayed her parents’ reservations, especially when a chance at higher education arose.

The following year, she entered Tuskegee Preparatory School on an athletic scholarship. Only sixteen years old, she worked while both studying and training. Part of her work involved sewing and mending of sports uniforms. This partly influenced her decision to earn, in 1946, her degree in dressmaking from Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black institution of higher learning in Alabama.

Her achievements while at Tuskegee were in both basketball as well as track and field. Playing guard on the women’s basketball team, she won three conference championships. Coachman also became the national champion in the 50-meter race, 100-meter race, 400-meter relay and the high jump, her specialty. In this endeavor, she captured the national title ten consecutive years, 1939 to 1948, all while barefoot!

Occurring at this time was World War II. Its launch led to the cancellation of world events including the 1940 and 1944 Olympic Games when Alice Coachman was at her peak. Many have speculated that if Coachmen was allowed to compete in those global competitions, she would have been a champion. In 1947, she left Alabama to matriculate Albany State College. There, she completed her Bachelor of Science degree in Home Economics, minoring in science, in 1949.

(No copyright infringement intended).

When the war ended in 1944, nations around the world prepared for the 1948 Olympic Games. Alice Coachman, who suffered an injury to her back, was hesitant to compete. However, she aced the tryouts, devastating the reigning national high jump record.

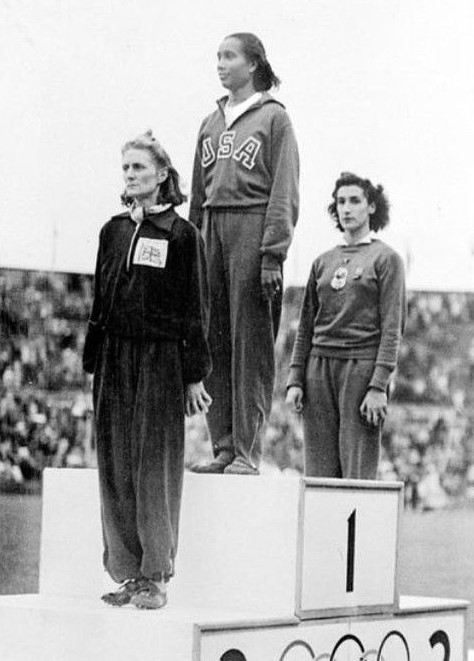

In 1948, Coachman, representing the United States, competed at Wembley Stadium in London, England. She faced talented and skilled adversaries, including Dorothy Tyler of England. With more than 83,000 guests watching, she cleared the high jump at 5 feet, 6 and 1/8 inches on her first jump. Tyler also cleared the bar at this height but it was on her second attempt. Micheline Ostermeyer, representing France, came in third.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Accomplishing this feat earned Coachman the first place rank. With this victory at the 1948 Games, Alice Coachman became the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal and the only American woman to win a gold medal!

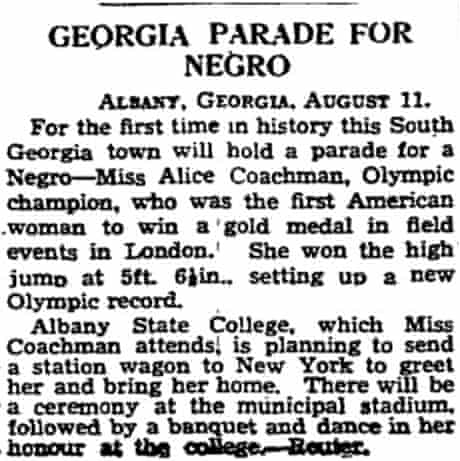

After receiving her medal from King George VI, she soon returned home to the States a heroine. Racism still impacted her achievement, as Coachman recalled that she was treated as inconsequential even by her own hometown. At her homecoming, Alice Coachman was forced to use a side door to enter and exit the segregated auditorium celebration honoring her. The mayor actually refused to shake her hand in congratulations.

Ironically, her home city of Albany created “Alice Coachman Day”, which included a 175-mile motorcade to celebrate her and her accomplishments. She attended an awards ceremony hosted by President Harry S. Truman and met with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Among the celebrations held throughout the country in her honor were parades and even a party given by jazz legend Count Basie.

(No copyright infringement intended).

After winning 25 AAU indoor and outdoor titles, Alice Coachman officially retired from athletics in 1948. Only twenty-four years old, she felt that she had reached her pinnacle, humbly proving it to herself, her parents, coaches and others.

However, she remained greatly respected and admired. Four years after her Olympic gold medal win, Alice Coachman became the first African-American woman to gain an endorsement contract. In 1952, the Coca-Cola Company signed her to internationally endorse their products. This endorsement included her and fellow trailblazer in track and field, Jesse Owens, being featured prominently in its billboards. Recognized as possibly the greatest and most famous person in the history of track and field, Owens, in the 1936 Olympic Games, was the first American to win four gold medals and break two international records!

(No copyright infringement intended).

Upon her retirement, Alice Coachman worked in her passions of education and training, including with Job Corps. To support young aspiring athletes as well as fellow Olympians retired from competition, she developed the Alice Coachman Track and Field Foundation.

On July 14, 2014, Alice Coachman passed away, having suffered cardiac arrest. She had health issues, including a stroke and respiratory difficulties, prior. In her life, she married twice. She divorced her first husband, N.F. Davis, with whom she had two children, Evelyn and Richmond; and she outlived her second husband, Frank Davis.

Numerous honors were given to recognize her historical impact and legacy. These include being named as one of the “100 Greatest Olympians in History” at the 1996 Summer Olympic Games held in Atlanta, Georgia and an honoree for Women’s History Month by the National Women’s History Project. She has been inducted into nine different halls of fame such as the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame. An honorary member of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, Alice Coachman was honored by her home city of Albany with its designation of Alice Avenue and Coachman Elementary School.

(No copyright infringement intended).

“I made a difference among the Blacks, being one of the leaders … If I had gone to the Games and failed, there wouldn’t be anyone to follow in my footsteps. It encouraged the rest of the women to work harder and fight harder.”

~ Alice Coachman