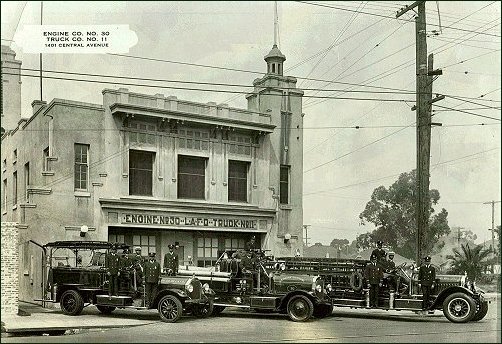

Presently, the only museum in the United States dedicated to honoring the rich legacy of Blacks in fire safety, the African American Firefighter Museum (AAFM) is located at 1401 South Central Avenue in Los Angeles, California. Housed in Fire Station #30, the mission of the museum, as per its website, is “dedicated to collecting, conserving and sharing the heritage of African American Fire Fighters through collaboration and education.”

In celebrating the one-hundred years that African-American firefighters served Los Angeles, the AAFM opened in 1997. While it was originally believed that the first African-American firefighter served in 1897, the Los Angeles Times reported to the museum that, in fact, they discovered that the history began several years earlier. The newspaper informed the AAFM that Sam Haskins was the first fireman of African descent to be hired, in 1892, by the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD); in 1895, he was killed while responding to a fire emergency.

Fire Station #30 was established in 1913 and its selection as the site of the museum is most appropriate. From 1924 until 1955, Fire Station #30 and Fire Station #14 were the two stations that housed Black firemen in Los Angeles. In the documentary, Engine Company X, the African American Firefighter Museum is saluted as “a monument to a civil rights movement that began within these walls.”

(No copyright infringment intended).

During the Great Migration, a mass movement of African-Americans from the rural South beginning in 1916, many settled in California. However, in numerous instances, the overt discrimination against and segregation of Blacks in the West were highly similar to that suffered in their previous southern environments. One of these environments was the workplace of the local government and, specifically, in the area of fire safety for those Blacks who settled in Los Angeles.

The AAFM exhibits detail the heinous sufferings, shining accomplishments and immense contributions of African-American firefighters. Personal items, firefighter paraphernalia and instruments, newspaper articles, photographs, letters, art and a memorial to those Black fire personnel lost in the 9/11 attack comprise the exhibits. The first floor of the museum is dedicated to African-American firefighters who serve in Los Angeles. The second floor is dedicated to African-American firefighters who serve throughout the United States.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Visitors to this institution will learn of the strength, dedication and determination that these men had in serving the community. In “African American Firefighters Museum”, contributed by anhie to Atlas Obscura, incidents of racism include “… countless stories of how ‘Colored’ firefighters were forced to sleep on isolated cots near the bathroom, away from White firefighters. Treated as second-class citizens, they were forced to scrub toilets, eat alone in silence, and were told to stand four human spaces away from their White colleagues during line-ups and inspections.”

On the museum’s site, Fire Captain Brent Burton, past president of the African American Firefighter Museum, further discussed the challenges that Blacks had to overcome during segregation. In one account, he shared that in 1924, the city of Belmont “was a very deserted place. However, when the (Belmont High) school was built, the department, community and school district became concerned about school children looking at African American firefighters in positions of authority; therefore, they relocated the African American firefighters to Station #30. The particular area where the station is located happened to be where many Blacks were beginning to segregate toward when they migrated to Los Angeles. In 1936, the LAFD opened Station #14 at 34th Street and Central to Blacks.”

In 1955, the Los Angeles Fire Department became integrated and African-American firefighters were transferred to other stations throughout the city. Sadly, they were treated with intense animosity. Burton gave insight to this matter when explaining a plaque, “Colored Served in the Rear”. He explained, “When the Black firefighters were integrated, they were not allowed to eat with the White firefighters and when they did eat, they had to eat by themselves, bring in their own utensils – pots, pans, plates, cups, to eat on and eat with. They were forced out of the kitchen while the White firefighters ate.”

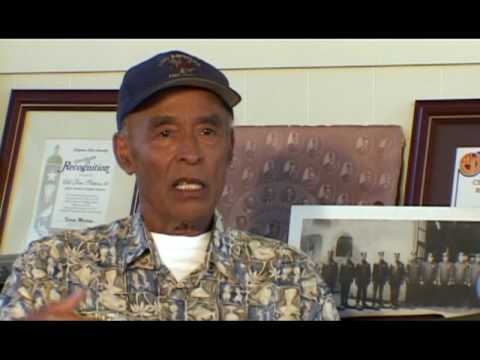

The late firefighter Arnett Hartsfield; other African-American firefighters who were known as the “Stentorians”; the National Association for the Advancement for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); and local citizens were integral to the end of segregation within the LAFD. A graduate of University of Southern California Gould School of Law, Hartsfield, in the 1940s and 1950s, led the fight for integration. He emphasized that the “integration” provided within the city fire department was, instead, isolation.

It was Hartsfield who submitted to the media a photograph taken by firefighter Rey Lopez. The picture was of a sign, “White Adults”, that had been posted in an integrated fire station. The publishing of the photograph revealed the rampant racial discrimination that African-Americans experienced. Burton added more details to this type of hazing when he, on the AAFM site, talked of Ernie Roberts. An African-American firefighter, in 1955, he was sent from Station #30 to an integrated fire house. Upon arriving, he was met with abuse from White firefighters who, as per Burton, “took Ernie’s pillowcase while he was out, used it as toilet paper in the restroom, replaced it on his bed and turned the lights out.” This was passed off by the White firefighters as a “practical joke”.

Hartsfield, who worked as a firefighter with the Los Angeles Fire Department from 1940 until 1961, was given the nickname, “Rookie”. The term was short for “The Eternal Rookie” because he was never promoted in his twenty-one years of service with the LAFD.

(No copyright infringment intended).

However, he and the Stentorians were undeterred. These African-American men who served as firefighters in Los Angeles united to attain the opportunities and advancement which had been historically denied to them. In the AAFM, numerous accounts of the Stentorians, which Hartsfield co-founded, are highlighted. There are also, as anhie wrote, “…awards and achievements of Black firefighters – both men and women – who have since gone on to hold prominent positions of power.” The Stentorians are still actively involved with issues that affect African-American fire safety personnel who operate within the city and county fire departments of Los Angeles.

The African American Firefighter Museum, as a non-profit organization, is supported by donations and operated by volunteers. Hartsfield, who served as the museum’s historian and on the Board of Trustees, was the inaugural recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Los Angeles Fire Department. He volunteered two days a week and was considered by the Stentorians and museum community as their “most cherished volunteer.” Firefighter Arnett Hartsfield passed away in 2014; he was 96 years old.

The African American Firefighter Museum continues to support African-Americans in the field of fire safety, even supporting recruitment efforts of the LAFD. Their community outreach also engages youth with the Junior Firefighter Youth Foundation. Created by Burton in 2003, the foundation operates on several elementary and secondary school campuses. In providing the Junior Cadet and Future Firefighter programs, their mission, stated on the AAFM site, is to “mentor, train and develop young minds for the future. We provide educational lectures and exercises that stimulate young minds to make better choices so they can become productive citizens.”

Visually chronicling the progressive work of these African-American firefighters is Engine Company: X. This Chin Thammasaengsri documentary, produced by Westlake Signal Group, was a selection of the Pan African Film Festival. It is often televised on local Los Angeles stations and during every Black History Month. Segments of the film may also be viewed on YouTube.

The museum is open on Tuesday and Thursday, from 10 am until 2pm and on Sunday, 1pm until 4pm; admission is free. Tours may be self-guided; group tours, led by a docent, can be arranged. Items of memorabilia may be purchased from their shop; available are a tee, a patch and two art pieces, Suspenders and Turnout. Created by Black artist Evita Tezeno, these two pieces are signed and part of numbered limited-run of 250.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The African American Firefighter Museum is also available for rental, as stated in their literature, to “host events such as meetings, luncheons, dinners, banquets, book signings, film viewings, jazz festivals, social dances, receptions and retreats.”

As Fire Station #30, this building had been an icon of discrimination against and oppression of Blacks in fire safety.

(No copyright infringement intended).

How wonderful it is that it has been converted into a cultural institution that celebrates the perseverance and achievements of African-American firefighters!