“With the tragic death of Martin King when he was assassinated, it was A. Philip Randolph who went on carrying the struggle for another twenty years … it’s only the rare young student or older person in America who has any clue who A. Philip Randolph is …”

~ Larry Tye, Author and journalist

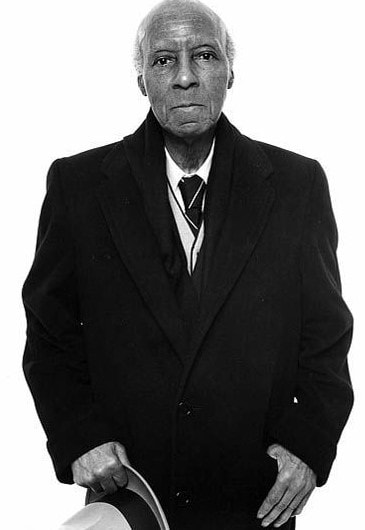

On April 15, 1889, a baby boy was born in Crescent City, Florida to Reverend James and Elizabeth Randolph. The couple’s second son, they would name him Asa Philip. His parents were professionals, his father being a minister in the African Methodist Episcopalian Church and his mother being a seamstress. Both were strong supporters of equal rights for all, especially African-Americans.

When Asa was only two years old, his parents moved their family to Jacksonville, Florida, where Asa lived until young adulthood. Although the community to which the Randolph family moved was progressive for Blacks, racial discrimination and violence were never far removed. According to the biography of A. Philip Randolph featured by the American Federation of Labor & Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) on its website, “From his father, Randolph learned that color was less important than a person’s character and conduct. From his mother, he learned the importance of education and of defending oneself physically, if necessary. Randolph remembered vividly the night his mother sat in the front room of their house with a loaded shotgun across her lap, while his father tucked a pistol under his coat and went off to prevent a mob from lynching a man in the local county jail.”

An exceptionally bright student, A. Phillip Randolph matriculated Cookman Institute, one of America’s first institutions of higher learning for African-Americans; in 1923, Cookman Institute would merge with the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls. The training school, founded by educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune, and the institute formed what is presently known as Bethune-Cookman University. At Cookman, Randolph excelled in academics, including literature and drama; extracurricular activities such as choir; and sports, like baseball, which he aced. Crowning these accomplishments, Randolph would graduate as the valedictorian of The Class of 1907.

Upon graduation, Asa Randolph moved to the Harlem community of the Manhattan borough of New York City in 1911. Although he wanted to become an actor, he, honoring his parents’ wishes in him becoming formally educated, chose to attend City College. He studied sociology and English literature. During this time, he worked several jobs of service, including as a waiter and a porter. Highly concerned with African-Americans’ lack of equitable access for employment, Randolph and Chandler Owen, a law student at Columbia University in the City of New York, created in 1912 the Brotherhood of Labor, an employment agency. Randolph and Owen, who shared similar intellectual interests and views on socialism, significantly the ideologies of the Industrial Workers of the World, felt their agency was integral to organizing Black workers. One of the earliest efforts of Randolph to organize labor occurred when he, working as a server on a steamship, spurred other Black workers to unite against the terrible living conditions imposed upon them.

During this time, A. Philip Randolph began courting Lucille Campbell Green, a graduate of Howard University. Also a graduate of Lelia Beauty College, founded by Madame C.J. Walker, she owned a prosperous beauty shop on 135th Street in New York City. Green and Randolph married in 1914. Green, a widow, was a successful entrepreneur who financially supported them both; the couple would have no children. Shortly after their marriage, she was able to publish The Messenger, a periodical co-founded by Randolph, and distributed it from her salon which catered to affluent African-American women. Because of her support and lack of children to rear, Asa was able to further develop his community interests even beyond his fight for labor and civil rights. This development included organizing a drama society, Ye Friends of Shakespeare, in Harlem.

His labor interests continued to expand and Randolph often could be found on the corner of 135th and Lenox Avenue, “the soapbox corner of Harlem”, espousing the virtues of socialism and need to be conscious and proactive about class. At this time, Randolph also became a member of the Socialist Party of America.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Randolph and Owen, supported by the Party, continued their collaboration in the form of media. In 1917, William White, president of the Headwaiters and Sidewaiters Society of Greater New York, sought the pair to edit Hotel Messenger, the society’s private magazine. Later that year, Randolph and Owen published the political periodical, The Messenger. This monthly magazine, which contained essays, art and poetry of Black writers, was considered radical and highly dangerous for several reasons. It urged Blacks to resist the draft, opposed the involvement of the United States in World War I (called “The Great War” at the time) and prompted African Americans to unionize.

Detailing life for Black workers, the topics in The Messenger ranged from demand for higher wages to inclusion in the armed forces and war industry; the latter would continue to be a great passion of Randolph’s for the next several decades. His attempts to unionize African American laborers included elevator operators in New York in 1917 and organizing dock and shipyard workers in Virginia in 1919, when he became the president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America. This union would disband two years later.

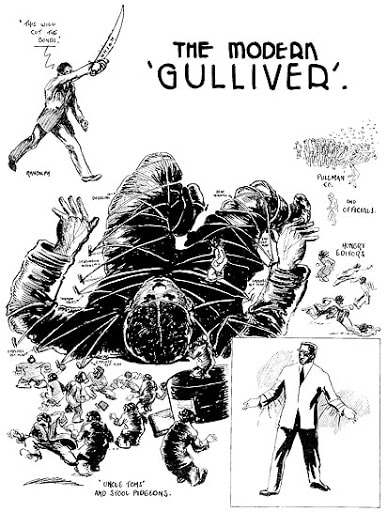

Racial discrimination remained entrenched in practically every institution that existed in the United States. These racist beliefs and practices, both subtle and overt, empowered the White labor movement to bar, by whatever means, the Black workers and their efforts to organize. Perhaps the greatest number of workers to be professionally affected by this racial discrimination and segregation were the Pullman porters.

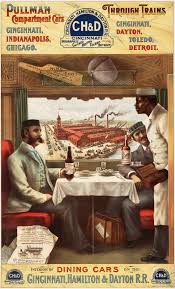

The Pullman Car Company, founded in 1867 by George Pullman, manufactured and leased railroad cars and, according to the “Pullman Company” stub of American Rails website, “… became the face of the passenger train industry during the Golden Age of rail travel through the first half of the 20th century.” Pullman cars soon differed from their competition, as they upgraded their cars beyond mere transport; they were so luxurious that they were referenced as “rolling hotels on wheels” and “traveling Pullman” meant to travel in high style. What cinched the cars being representative of the lifestyles of the upper echelon were the Pullman porters, Black men who, as service personnel, were locked in the lease to the railroad companies.

Pullman played to the racism of his potential clients who saw Blacks as inferior and should be subservient to Whites. He purposely sought Blacks who had been enslaved, as he felt they knew how to treat Whites, and intentionally hired darker-skinned Blacks to meet his nefarious need.

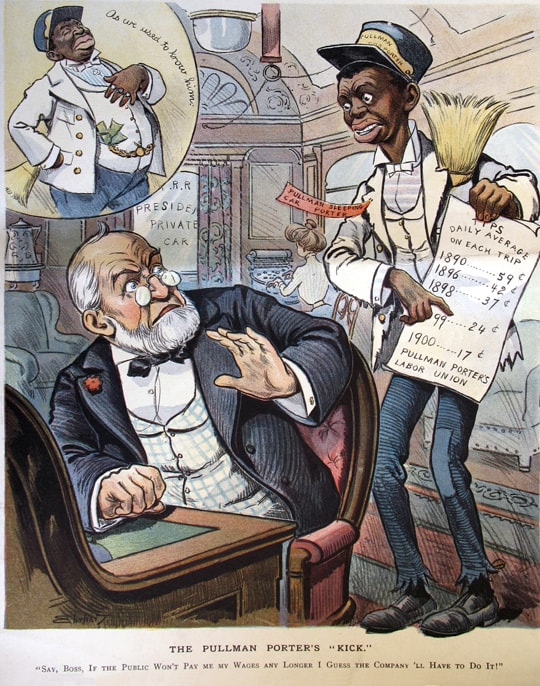

The Pullman Car Company provided stable employment. However, Pullman porters suffered long hours of work; low pay; taxing work; diminished hours of sleep; 24 hours/day on call responsibility; excessive absences away from loved ones and Pullman’s severe code of conduct. Because these Black men worked much longer hours under more stressful conditions than their White counterparts for less than half the pay and also were excluded from certain positions, the porters attempted, in 1909, to form a union. The Pullman porters were intimidated and threatened with lower wages, loss of jobs and some were even fired for attempting to form a union.

After several discussions, three men representing the porters met with A. Phillip Randolph. Randolph, who formerly worked as a porter, was highly supportive of the Pullman porters and their plight, covering articles on them in The Messenger. Randolph, who had been unsuccessful four times prior as an organizer, was sought because he was actively supportive, but also because he was astute, highly articulate and unable to be threatened, employment-wise, by the Pullman company. Randolph accepted their request to lead them and on August 25, 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was founded. Their motto was “Fight or Be Slaves!”

The forming of the BSCP was critical because by the 1920s, Blacks were employed by Pullman as porters but also as dining car waiters, lounge car attendants and onboard servers as well as firemen, maids, and railcar attendants. With over 20,000 BSCP members employed by Pullman, these Blacks comprised the largest category of Black labor!

Randolph worked tirelessly, despite constant threats and consistent attempts to bribe him. He firmly stood his ground and was considered by many, especially President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, to be of great integrity. The Black workers continued to face discrimination, firings and violence. In 1928, Randolph, vice-president C.L. Dellums and other leaders within the BSCP planned to strike after mediation talks between the BSCP and the Pullman Company failed to reach a mutually beneficial compromise under the Railway Labor Act. The Railway Labor Act, passed in 1926, was created to govern labor relations in the railroad industry and sought to resolve labor disputes through arbitration, bargaining and mediation.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The Pullman Company relayed that the workers would be readily replaced, nullifying the potential efficacy of Blacks undertaking a strike. As members of the BSCP became frustrated, angry and fearful, membership in the union drastically diminished and by 1933, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters only contained approximately six hundred-and-fifty members. The treasury of the union was so depleted that the utility services in its headquarters had been disconnected due to lack of funds to pay its bills.

However, the tides would change in favor of Randolph and the BSCP in 1934. New amendments to the Railway Labor Act provided rights, under federal law, for the porters. In response to this revamped act, membership soared to greater than 7, 000 members. Negotiations between the Pullman Car Company and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters were undertaken. In 1935, the railroad car company agreed to contract with the Black union, who had become certified to be the exclusive collective bargaining representative of the Pullman porters.

In 1937, the Pullman Company finally recognized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, signed a labor agreement to reduce their hours with a decreased work week; pay for overtime; and increase the pay of these men. $2, 000,000 (USD) was set aside for this increase. A. Phillip Randolph made possible the first African-American labor union in the United States. He led the BSCP to join the CIO and leave the AFL until the latter established a more equitable relationship for the BSCP. The Brotherhood would re-establish connection with the AFL when it merged with the CIO in 1955. According to the AFL-CIO website, Randolph referenced this win as the “first victory of Negro workers over a great industrial corporation.”

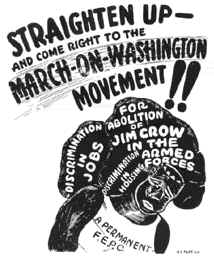

The BSCP’s defeat of the Pullman company was an incredible feat that would set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement, as Randolph became popularly known as an activist and spokesman for the Black laborers, civilians and military personnel. Blacks who worked in the defense industry still suffered pervasive racial discrimination and segregation and Randolph called out the military and the president for this. In late 1940, President Roosevelt refused, via executive order, to ban this discrimination.

Randolph’s response included, “There must be no dual standards of justice, no dual rights, privileges, duties or responsibilities of citizenship. No dual forms of freedom,” and he called for thousands of Black patriotic citizens of the United States to participate in a march on Washington, D.C. There was such great support that the original goal number of ten thousand marchers expanded to one hundred thousand. Attempting to stave off the march on the nation’s capital, President Roosevelt, as stated on the AFL-CIO website, “ … issued an executive order on June 25, 1941, six days before the march was to occur, declaring ‘there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.’” The Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) was also created by President Roosevelt in order to oversee his new Executive Order 8802.

Due to the FEPC and labor shortages, there was a dramatic increase of African-American employment within the next two years. Because of new and more fair opportunities for stable employment, significantly within the defense industry, a mass exodus of approximately six million Blacks from the American South to defense areas within northern and western cities occurred.

A. Philip Randolph continued fighting for equitable integration and in 1946, formed the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service; the name of this committee was later changed to the League of Nonviolent Civil Disobedience against Military Segregation. With this organization, he called for numerous changes, including that Black and White young men, especially in the military, peacefully denounce Jim Crow conscription. Due to needing the Black vote for his re-election and increasing Black political power, on July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman desegregated the U.S. military with Executive Order 9981.

Randolph continued his fight to end segregation and in 1950, he co-organized the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. This conference provided the opportunity for organizations battling racial discrimination to meet and coordinate plans of legislative action.

In 1955, the AFL merged with the CIO and A. Philip Randolph was elected as its vice president. Although he used his position to continue to advance efforts for desegregation and promote civil rights, he still found himself protesting the racial prejudice within the newly-formed labor organization. As a result, in 1959, Randolph co-founded the Negro American Labor Council, of which he served as president (1960-66). Its purpose was to fight against racial prejudice and discrimination within the AFL-CIO.

During this time, the efforts of Randolph extended even more broadly into civil rights and his efforts include organization of a prayer pilgrimage to Washington, D.C. and development of a youth march. The purpose of both was to make real the federal right of desegregation whose implementation was being purposely stalled, primarily in the South.

(No copyright infringement intended).

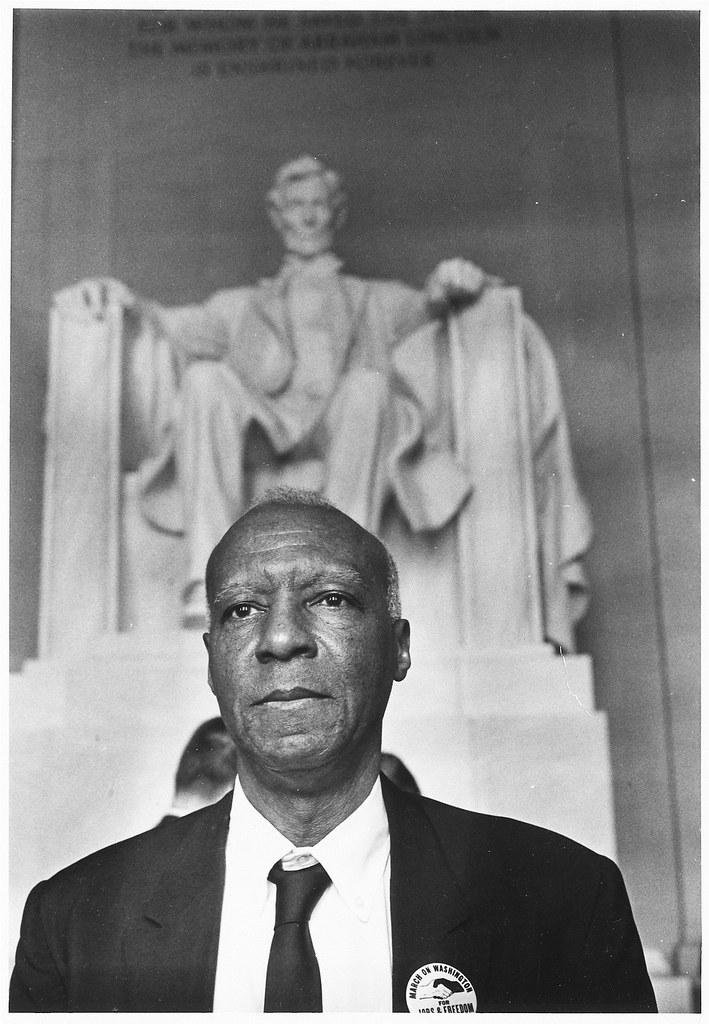

A. Philip Randolph’s potential use of the Black citizens’ march on Washington in 1941 and tactics of utilizing civil disobedience in order to end segregation in the labor industry and military prompted civil rights activists of the 1960s to view his methods as successful in order to meet their goals. The Civil Rights Movement recognized his genius and work by naming him the chair of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and kept the movement as nonviolent. Drawing an integrated crowd of nearly two-hundred and fifty thousand persons, its purpose was to support the civil rights policies for African- Americans. Unfortunately, his wife was unable to share in this experience, as she passed away earlier that year.

For his contributions to humanity and society, A. Philip Randolph was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. In 1968, Randolph retired from serving as president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters for more than forty years.

Later that year, he assumed the role of president at the newly-created A. Philip Randolph Institute of the AFL-CIO. Located in Washington, D.C., it was comprised of community and labor leaders. The purposes of this institute involved studying cause and effects of poverty upon citizens, create effective solutions to counter said causes and promote trade unionism within the Black community. The A. Philip Randolph Institute was co-founded by Bayard Rustin, his mentee and organizer of the 1963 march. The Institute was built upon themes Randolph highlighted in his poverty-elimination program, “Freedom Budget for All Americans”, that he proposed at a conference held at the White House in 1965.

During this time, Randolph continued to serve within the AFL-CIO, including its Executive Council, until 1974. Due to a heart condition and hypertension, Randolph retired from public life. Sadly, he had later been mugged on three separate occasions, causing him to move from his long-time residency in Harlem to live in the Chelsea neighborhood. He spent the final years of his life composing his autobiography.

On May 16, 1979, Asa Philip Randolph passed away in his bed at his home; he was ninety years old. His body was cremated and his ashes were interred at the A. Philip Randolph Institute.

His enormous and powerful influence has inspired many and numerous creations have been developed in his honor. These creations include schools and university buildings located in Florida, New York and Pennsylvania; streets and a boulevard throughout the country; a square in the Harlem community and a museum in Chicago, Illinois.

Additionally, a documentary, A. Philip Randolph, by PBS and the film, 10,000 Men Named George, by Robert Townsend were produced. Randolph was named as one of “100 Greatest African Americans” by Afrocentric scholar, Molefi Kete Asante. A statue of Randolph was erected in Back Bay commuter train station in Boston, Massachusetts and another in the concourse of Union Station in Washington, D.C. Randolph was further honored by the U.S. Postal Service when he was installed on a postage stamp in 1989, as well as by Amtrak when they named one of their most prominent sleeping cars, Superliner II Deluxe Sleeper 32503, the “A. Philip Randolph”.

“A community is democratic only when the humblest and weakest person can enjoy the highest civil, economic and social rights that the biggest and most powerful possess.”

~ A. Philip Randolph

For greater enlightenment...

-

10,000 Men Named George

-

A. Philip Randolph - Civil Rights Pioneer | Biography

-

An Anthology of Respect: The Pullman Porter National Historic Registry

-

For Jobs and Freedom: A Black Nouveau Special/ Program

-

Randolph Reading Pledge of the March on Washington

-

“Rise from the Rails: The Story of the Pullman Porter” --Democracy Now!