“Paul Laurence Dunbar is one of America’s greatest treasures.”

~ nikki giovanni, poet

There is such a wonderful opportunity to learn and to celebrate the depth and breadth Paul Laurence Dunbar created in his work, especially regarding the diversity of Black cultural life. Although he wrote twelve books of poetry, he was so much more than simply a poet. In his brief life, which spanned thirty-three years, Dunbar authored articles in international publications; four novels; four collections of short stories; lyrics for a musical; and a play!

As activist and diplomat James Weldon Johnson remarked about his very good friend, “Paul Laurence Dunbar stands out as the first poet from the Negro race in the United States to show a combined mastery over poetic material and poetic technique, to reveal innate literary distinction in what he wrote, and to maintain a high level of performance … he was the first to rise to a height from which he could take a perspective view of his own race … he was the first to see objectively its humor, its superstitions, its short-comings; the first to feel sympathetically its heart-wounds, its yearnings, its aspirations, and to voice them all in a purely literary form.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

On June 27, 1872, Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio to Joshua and Matilda Dunbar, who had married on Christmas Eve in 1871. During the Civil War, his father had escaped enslavement in Kentucky and fled, with the guidance of the Quakers, to northern Canada on The Underground Railroad. Joshua then moved to Massachusetts, where he volunteered for the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. This infantry regiment was one of the earliest Black units to serve in the war. Joshua Dunbar would also serve in another colored unit, the 5th Massachusetts Calvary Regiment. Joshua earned the rank of sergeant and served in the 5th Regiment until the end of the Civil War.

Upon being emancipated from being enslaved in Kentucky, widow Matilda Murphy, moved to Dayton, Ohio with her family members, including her two children, Robert and William, from her first marriage. She met and married Joshua Dunbar after moving to Dayton. Unfortunately, their marriage was troubled and it ended after the birth of their daughter, Elizabeth. They were divorced in 1876, the same year that Elizabeth passed away at the age of two years old. Joshua would eventually live at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, where Paul would regularly visit him. Joshua passed away from pneumonia when Paul was just thirteen years old. Paul dearly loved his father, who was the inspiration of one of Paul’s most beloved poems, “The Colored Soldiers”.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Matilda strongly believed that Paul was a blessing to her and treated him as such, especially in ensuring that he became educated. She often entreated literate children with baked sweets in exchange for them teaching her how to read so she could further help Paul and his brothers advance. Paul wrote his first poem at the age of six and publicly recited poetry when he was nine years old.

As the only African-American student at Central High School, Dunbar was a member of the debate club, editor of the school newspaper and president of the school’s literary society. He, as a member of the Class of 1890, also composed and presented the official class poem upon their graduation. When he was a teenager, his poems were published in the local newspaper of Dayton. Paul also composed and edited a newspaper, Dayton Tattler, that covered interests of the African-American community of Dayton. It was published by future aviators, Wilbur and Orville Wright, the latter of whom was Paul’s classmate at Central High. The paper would cease being printed after only three issues.

Despite his exceptional skills, proven body of work and high school diploma, racial discrimination was rampant and Paul Laurence Dunbar was not hired for any professional work. Additionally, the opportunities and monies needed to further his education were unavailable. To survive, he accepted the low-paying position of an elevator operator in the Callahan Bank Building in the rapidly-developing downtown of Dayton. During the lulls on his job and his breaks, Dunbar composed poetry and short stories. When a former teacher invited him to speak at a local convention of writers, he was so well received that it, ultimately, motivated him to publish his first collection of poetry, Oak and Ivy, in 1892. The book is written in two separate parts: Oak, the larger portion, is written in standard verse and Ivy, the shorter section, is written in dialect. His book became a success; he even personally sold it to those who rode his elevator. He was able to get five-hundred copies of his book printed on credit by United Brethren Publishing House. He sold all of them within two weeks and paid the publishing house in kind.

Paul Laurence Dunbar quit his job at the Callahan Bank Building to report, as a representative of the Dayton Herald, on the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1892. While there, he recited poems on Colored Americans Day and earned the respect of those in attendance, including abolitionist, orator and leader Frederick Douglass.

Dunbar soon began gaining more engagements to speak and write throughout the country. He received many praises from others, regardless of race, education or class. Although Blacks felt conflicted about his writing styles, a number of them, including his great friends, scholar, author and sociologist, W.E.B. DuBois and Colonel Charles Young of the U.S. Army were supportive. Douglass referred to Dunbar as “the most promising colored young man in America”. Whites, significantly, Charles Thatcher, an attorney, and Dr. Henry Tobey, a psychiatrist, also supported Dunbar financially and otherwise. With the aide of Thatcher and Tobey, Dunbar published his second collection, Majors and Minors.

The book received rave reviews, most notably from “America’s leading man of letters”, William Dean Howells, who referred to Dunbar as “a prophet without honor in his own country … his poems are evidence of the essential unity of the human race.” With this glowing confirmation from Howells published in Harpers Weekly in 1896, Dunbar’s popularity skyrocketed. As a result, he toured the United States and England, sharing and promoting his works. His success would prompt him to combine his first two books as one volume, Lyrics of a Lowly Life, and feature Howells as the author of its introduction.

Dunbar would extend his talents beyond writing poetry by composing lyrics to songs, collaborating his poems to classical music, writing articles concerning Blacks and society, co-founding an academy dedicated to African-American scholarship and authoring novels.

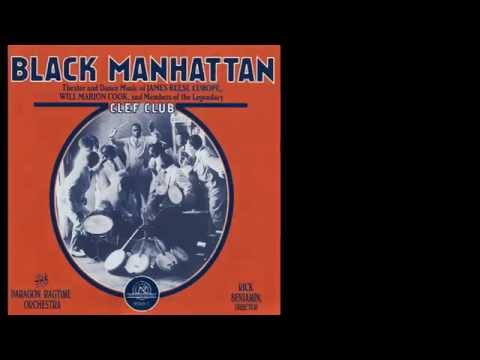

Clorindy, (also known as The Origin of the Cake Walk) is a one-act musical by composer Will Marion Cook with Paul Laurence Dunbar as the librettist. The musical premiered in 1898 and was the first Broadway musical with an all-Black cast, including Ernest Hogan, the first African-American entertainer to produce and star in a production on Broadway (1907, The Oyster Man). Opening at the Casino Theatre’s Roof Garden on July 1, its successful premiere prompted Cook to exclaim, “My chorus sang like Russians, dancing meanwhile like Negroes, and cakewalking like angels, Black angels … Negroes are at last on Broadway, and here to stay!”

Dunbar and Cook will collaborate again, bringing to the stage, In Dahomey, an adaptation of Jesse Shipp’s novel. In Dahomey, is the first full-length musical written and performed by Blacks to be performed at a major Broadway theatre; it premiered at The New York Theatre, February 18, 1903. It was produced by vaudeville greats, Bert Williams and George Walker, who also starred in it. After 53 performances of a successful run, it closed on April 4, 1903. Its widely successful tours in the United States and the United Kingdom, including a command performance at Buckingham Palace, lasted four years.

The inspiration for this musical stemmed from actual events of the San Francisco Midwinter Fair of 1894 in which Dahomeans protested about being put on display (think “a human zoo”). They were substituted with African-American actors, including Walker and Williams. In the previous year, Chicago’s World Fair also “used” Dahomeans in the same manner, but they did not like the cold weather and returned home, causing a delay and subsequent hiring of African-Americans in 1894. The influence that the real Africans had on the African-Americans, who had had little to no frame of reference to anything positive as it related to African culture and identity, was profound. This prompted Williams and Walker to produce In Dahomey!

In 1927, “In Dahomey”, a song inspired by Dunbar, Cook and Shipp’s musical and actual events, was featured in Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II’s, Showboat, one of the most famous shows in Broadway history. The incorporation of this song, according to educator Daniel Atkinson, illustrates “… the deep-seeded roots of White supremacy in American theater. Further, there would be no frolic, syncopation, and a whole lot more in American theater without African retention of African-Americans. Despite this, Africans are portrayed as simple, primitive and lacking merit. Basically, Black subjugation was and continues to be part of the status quo and we have just [gotten] better at encoding and excusing it rather than eradicating it.” This type of racism would beleaguer, in a myriad of ways, many Blacks, including Dunbar, throughout their lives.

In 1897, Paul Laurence Dunbar met English composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, in London. Having set several of Dunbar’s poems to music, a joint recital between Coleridge-Taylor and Dunbar was arranged in London. Performed at the patronage of US Ambassador John Milton Hay, it had been organized by Henry Francis Downing, an African-American playwright and London resident. Dunbar and other Blacks encouraged Coleridge-Taylor to draw inspiration and pride from his Sierra Leonean ancestry and the music of the Africa.

Regarding the political and social conditions for African Americans in the United States, Paul Laurence Dunbar was also active in the area of civil rights and the upliftment of African-Americans. He was a participant in the March 5, 1897, meeting to celebrate the memory of abolitionist and friend, Frederick Douglass. Many of those in attendance would work to create the American Negro Academy (ANA). Led under the guidance of Rev. Dr. Alexander Crummel, the American Negro Academy was the first organization in the United States to support African-American academic scholarship. Encouraging classical academic studies and liberal arts, it operated from 1897 to 1928.

The founders of the ANA were primarily artists, authors, educators and scholars. They included Dunbar; Crummell and Senator Blanche K. Bruce (MI). Activist, attorney and historian, John Wesley Cromwell; U.S. Army chaplain and Buffalo Soldier of the 25th U.S. Colored Infantry, Theophilus D. Steward; and African Methodist Episcopal minister and educator, Benjamin Lee, were also members of the ANA. Steward and Lee, who served as president of Wilberforce University (1876-1884) and editor of the Christian Recorder (1884-1892), were cousins. Later members of the American Negro Academy included James Weldon Johnson and John Hope.

Their first meeting on March 5, 1897 included eighteen founding members: Blanche K. Bruce, Levi J. Coppin, William H. Crogman, John Wesley Cromwell, Alexander Crummell, W.E.B. DuBois, Paul Laurence Dunbar William H. Ferris, Francis J. Grimké, Benjamin F. Lee, Kelly Miller, William Scarborough, John H. Smythe, Theophilus G. Steward, T. McCants Stewart, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, Robert Heberton Terrell and Richard R. Wright.

In 1898, after several years of courting, Dunbar eloped with Alice Ruth Moore, also a writer. Like his parents, their marriage was troubled. Paul’s diagnosis of tuberculosis added to their trials, especially as consumption of alcohol was commonly suggested to alleviate the illness’ symptoms. After a stormy altercation in 1902, Alice left him, never seeing him again. They never divorced and even after his death, she retained his surname and worked diligently to preserve and promote his legacy until her passing in 1935.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Paul Laurence Dunbar also was a novelist. His earlier works, The Uncalled, The Love of Landry and The Fanatics, contained only White characters and themes. Because he would be one of the first African-American authors to cross the color line, writing about White culture and its themes, his critics complained about his “handling of the material”, thus, rendering these works as commercial failures.

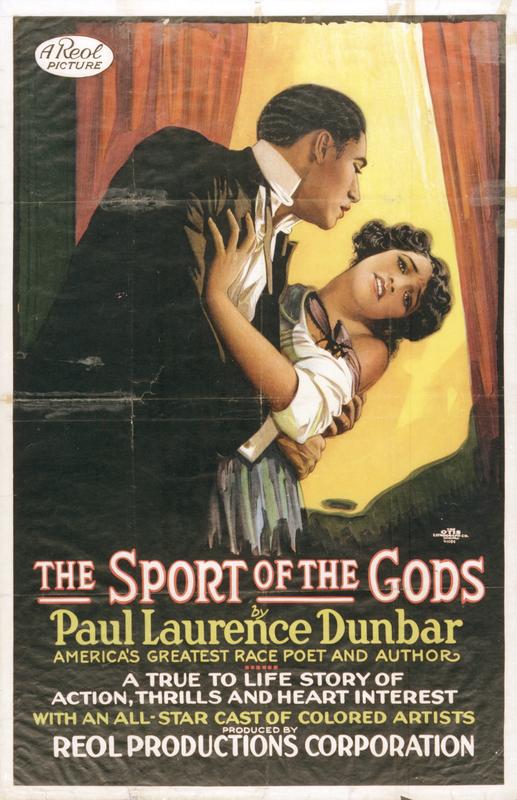

His final novel, The Sport of the Gods, centered upon the Hamilton family and the harsh realities they, as African-Americans, suffer living in urban New York upon being forced to leave their “home” in the American South. The Hamilton family are Berry, Fannie and their two children, Joe and Kitty. They work for the wealthy Oakley family, (Maurice, Leslie and Francis). Supporting characters include New Yorkers: Thomas, Mrs. Jones, Hattie Sterling, Mr. Skaggs a.k.a. “Skaggsy”, “Sadness”, Mr. Gibson (Fannie); and Southerners: Minty Brown and Colonel Saunders.

(No copyright infringement intended).

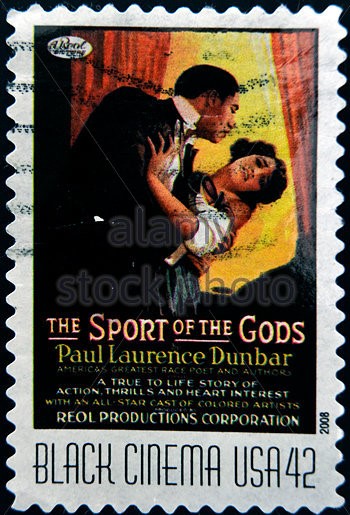

In 1921, English director Robert Levy, having secured the rights to the novel, released the film version, The Sport of the Gods. While the most prominent roles went to Black actors, Levy also selected Whites for supporting parts, marking a breakthrough in desegregation in the entertainment industry. Billboard advertised the opening on its primary page featuring motion pictures, “… making it the first time this level of recognition had ever been paid to a race film.”

William L. Andrews commented, “… in a world in which human beings … seem to be the ‘sport of the gods’ … the idea of progress or of struggle to bring about justice seems futile, if not meaningless.” This sentiment is posited almost 100 years after Dunbar wrote in the novel, “ … that the stream of young Negro life would continue to flow up from the South, dashing itself against the hard necessities of the city and breaking waves against a rock, –that, until the gods grew tired of their cruel sport, there must still be sacrifices to false ideals and unreal ambitions.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 2008, the United States Postal Service created a limited-edition series devoted to classic Black films. The promotional poster for The Sport of Gods movie was one of four images selected to be honored in the exclusive commemorative stamp series. The Sport of the Gods commemorative stamp was released in the “Vintage Black Cinema” series!

Despite suffering tuberculosis, Dunbar would continue to create prolifically, especially in the last three years of his life. For example, he wrote Sport of the Gods, a 300-page novel in thirty days! On February 9, 1906, Paul Laurence Dunbar passed away at the home he bought his mother in Dayton, Ohio. It’s said that he died, in his mother’s arms while reciting the 23rd Psalm. He was only thirty-three years old.

The creator of greater than 400 works in approximately thirteen years, the illustrious legacy of Dunbar includes a national monument, schools, university buildings, streets, a park, a hospital, a library and a lodge named in his honor. There is a documentary, Paul Laurence Dunbar: Beyond the Mask, written and directed by Frederick Lewis that is amazing. Many greats, including composer William Grant Still, poet and author Maya Angelou, author Toni Morrison and poet & writer Langston Hughes, have been immensely inspired by his work. Despite overt racial discrimination, financial instability and health issues, Paul Laurence Dunbar was truly a brilliant Black man who excelled in his brief life!

“People are taking it for granted that [the Negro] ought not to work with his head. And it is so easy for these people among whom we are living to believe this; it flatters satisfies their self-complacency.”

~ Paul Laurence Dunbar