The Buffalo Soldiers National Museum (BSNM) mission, according to its website, is “…to educate the public and to preserve, promote and perpetuate the history, tradition and outstanding contributions of America’s Buffalo Soldiers from the revolutionary War to the present.”

Located in Houston, Texas, the BSNM is able to achieve this mission utilizing various arms, such as the arts, archival research, exhibits, and outreach including educational programming, public tours, school visits and cultural workshops. The institution, also stated in their mission statement, “creates and disseminates knowledge about the history of the Buffalo Soldiers and their service in the defense and development of America.” This is critical in understanding American, especially African-American, culture.

In the post-bellum period of America, African-Americans, enrolled in the United States Colored Troops played a major role in the United States Calvary. During the Civil War, approximately two-hundred thousand African-American men fought for the Union and an estimated forty thousand men had made the ultimate sacrifice: their lives.

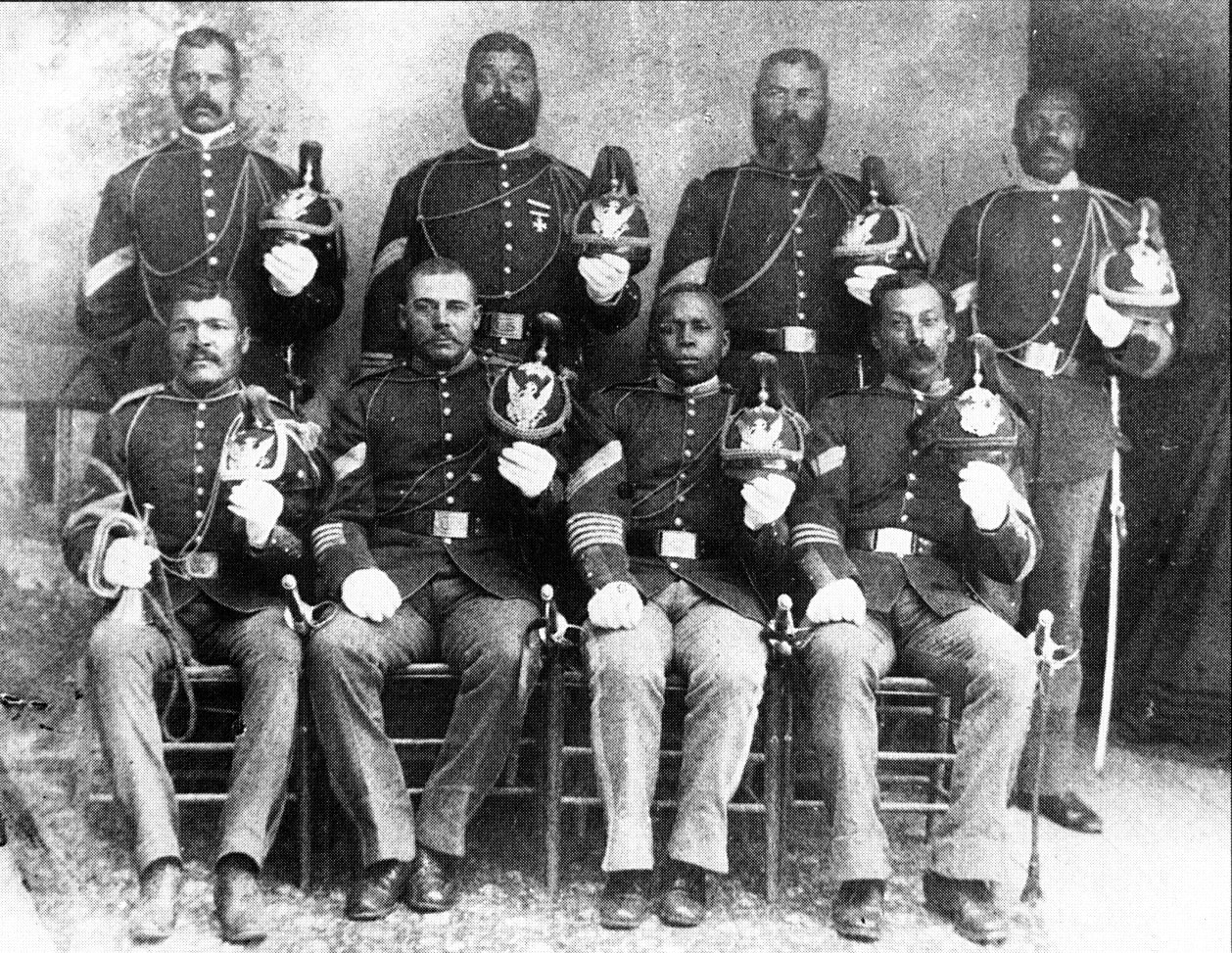

In July 1866, “Colored” regiments were raised by an Act of Congress. These new regiments were primarily comprised of Black men who were recently emancipated and many had been veterans of the Civil War. They had earned recognition for their bravery and 18 Black men had been awarded by the United States government its highest honor of combat, the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Around 1867, the term “Buffalo Soldiers” had become a popular moniker when describing the Black soldiers in these new regiments. It is commonly attributed to having been coined by the Cheyenne in salute to both the bravery and intelligence these men exhibited. It is also alleged that the term was created in recognition of the soldiers’ hair texture, and in some accounts, their skin color that was similar to the Cheyenne’s beloved buffalo. This comparison was considered by the regiments to be complimentary and the 10th U.S. Calvary even incorporated the image of a “buffalo” in creating their own flag!

Six regiments were created for frontier duty in 1866: the 9th U.S. Calvary and 10th U.S. Calvary and the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st U.S. Infantry regiments. The following year, the infantry regiments were consolidated into the 24th U.S. Infantry and 25th U.S. Infantry regiments.

Despite the widespread, overt racism and rampant discrimination shown towards these soldiers who were stereotyped, according to Robert V. Morris in Black Faces of War: A Legacy of Honor from the American Revolution to Today, as “disease carriers, cowards and prone to desertion”, soldiers in these 4 regiments served valiantly from 1866-1891. The motto of the 9th was “Ready and Forward” while the motto of the 10th was “We Can, We Will.”

When you visit the Buffalo Soldier National Museum, you will learn that daily life for the Buffalo Soldiers was extremely difficult. They were given inferior equipment as well as horses that were generally unfit and too old for military service. They even had to provide their own neckerchiefs, which were essential in protecting them from the dust-filled West.

The Buffalo Soldiers worked seven days a week with only the Fourth of July and Christmas given as holidays. Their barracks were badly-constructed, poorly-ventilated huts often infested with vermin. Because of their surroundings, illnesses of bronchitis, dysentery and tuberculosis were chronic. Their rations were limited to primarily beef, suet (animal fat), potatoes and beans; fruit or jam was an extremely rare treat, as Bruce Wexler wrote in How the Wild West was Won: A Celebration of Cowboy, Gunslingers, Buffalo Soldiers, Sodbusters, Moonshiners and the American Frontier.

The first Buffalo Soldiers were sent immediately to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Because of segregation at this time, these regiments were led by White officers. Colonel Edward Hatch would lead, for 23 years (1866-1889), the 9th U.S. Calvary, whose quarters were at Fort Stockton and Fort Davis in Texas. Colonel Benjamin Grierson would lead, for 24 years (1886-1890) the 10th U.S. Calvary, headquartered at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Colonel Joseph Potter commanded the 24th Infantry for 13 years and Colonel George Andrews headed the 25th Infantry for 21 years.

By the late 1800s, the Buffalo Soldiers would finally have Black officers. The first three Black graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point would be Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper (1878), Lieutenant John Hanks Alexander (1887) and Second Lieutenant Charles Young (1889). While Flipper and other Black officers served well, they were never allowed to command regiments. All too often, the obvious discrimination, sabotage and sanctioned abuse was overwhelming; the Black officers, according to Morris, were either dismissed or, like Flipper, resigned their commissions.

Years later, Young would not only serve in both the 9th U.S. Calvary and 10th U.S. Calvary, he would gain command of the 10th U.S. Calvary regiment. Young, as stated by the National Park Service, would also be the first Black man to achieve the rank of Colonel; the first Black superintendent of the U.S. National Park Service; first Black military attaché; and the highest-ranking Black officer in the U.S. Army until his death in 1922!

When you tour the BSNM, you will learn that these brave Black soldiers were constantly victorious in battles. They also performed duties, all too often overlooked, that included:

* Building and renovating military posts

* Stringing thousands of miles of telegraph wire

* Escorting stagecoaches, trains, cattle herds, railroad crews, survey parties

* Opening new roads

* Preparing maps of large tracts of unchartered territory

* Locating vital bodies of water for settlers

The 9th U.S. Calvary and the 10th U.S. Calvary often engaged in the most hostile of situations. They were commanded to retain Indigenous Americans, including the Apache, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa and the Lakota, on reservations. However, they also engaged them in battle. The Buffalo Soldiers, as Morris wrote, brought justice to “all outlaws of all races, cattle rustlers, White slave-trading Comancheros and bootleg-whiskey peddlers … United States marshals, county sheriffs, tax collectors and other civic officials could not have performed their duties without the escort from the Buffalo Soldiers …”

Visitors will also learn another vantage of American history. Congress would continue to violate the treaties they made with the Indigenous Americans. Violations included permitting, in 1870, White settlers to move into the areas reserved for the Lakota. This area is northwestern Nebraska and southeastern Dakota territory. The Lakota performed the Ghost Dance, which was a peaceful ritual. According to Alice Flanagan in We the People: the Buffalo Soldiers, in the ritual, they prayed to their dead ancestors that “the land would be soon be covered with new soil that would bury White people” and that peace would be restored to the Lakota.

On December 29, 1890, the 7th U.S. Calvary, which was all White, slaughtered at least 150 Lakota men, women and children in the valley of Wounded Knee Creek. The next day, that calvary was trapped at Drexel Mission near Pine Ridge reservation by the Lakota wanting to exact justice. The Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th U.S. Calvary rode 108 miles in less than one day and came charging to rescue Colonel George Forsyth and the 7th U.S. Calvary. The 9th U.S. Calvary was later commanded to care for the wounded Lakota and bury the dead.

The close of Western expansion and the Wounded Knee Massacre brought an end to the Indian Wars. Some Buffalo soldiers would leave the Army and become cowboys, entrepreneurs and farmers. Others chose to remain enlisted and made it a career. The Buffalo Soldiers made it possible for Arizona, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Utah to become part of the United States.

For more than 30 years, the 9th U.S. Calvary, 10th U.S. Calvary, the 24th U.S. Infantry and 25th U.S. Infantry, as Flanagan wrote, served “on the frontier from Montana to Texas, along the Rio Grande into New Mexico, in Arizona, Colorado and the Dakotas, and along the U.S.-Mexico border … they had built forts, protected settlers and mapped new territories.” An example of the Buffalo Soldiers’ bravery and mastery include the 9th U.S. Calvary’s defeat of approximately 1200 Kickapoo at Fort Lancaster, Texas where the 60 soldiers of Troop K were outnumbered 20-1 (December 26, 1867). Another example was the Battle at Beecher Island. Answering the request for protection of Colorado’s acting governor Frank Hall, 50 Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th overpowered, according to Wexler, a “combined force of over six hundred warriors from the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Brule and Oglala Sioux tribes … the regiment only suffered six fatalities.”

It should be noted that despite the harsh conditions, overt racism and rampant discrimination, the 10th U.S. Calvary had the lowest desertion rate in the entire United State Army! This is especially significant, Wexler asserted, considering the desertion rate during this period “was approximately 25 percent and was four times higher in White regiments than among the Buffalo Soldiers!”

One can surmise that among the difficult duties that had been commanded to the Buffalo Soldiers was to forcibly remove the Indigenous Americans from their homelands onto reservations. While this greatly assisted in settling the American West by Whites, it was done by denying freedom, equity of treatment and opportunity to the Indigenous Americans.

Andrew Johnson, as president of the United States, formed the Indian Peace Commission, which forced the many Indigenous American nations off the land they had been living on for tens of thousands of years onto U.S. government-designated reservations. Over the next several years, the U.S. government would make treaties with these nations, who would suffer the greatest losses. These losses included their cultural values and identities, their ties to their ancestral lands, the great buffalo, and their lives.

While the Buffalo Soldiers were forced to retain the Indigenous Americans from being able to leave the reservations, they were rarely granted cooperation in keeping White settlers, the “Boomers” out. In 1879 alone, the Boomers made 9 separate attempts to set up illegal settlements in the areas reserved for the Indigenous Americans!

In 1879-80, the 24th U.S. Infantry and 10th U.S. Calvary became heavily involved in the Apache Wars. A person of great interest was the Apache chief, Victorio, who was credited with the Alma Massacre of several White settlers in 1880. The 10th is noted most for its bravery in battle at Tinaja de las Palmas and at Rattlesnake Springs, New Mexico. Victorio was forced to flee back into Mexico, where he was executed by Mexican troops. During the Indian Wars (1866-1890), eighteen enlisted men were awarded the Medal of Honor. Fourteen of these recipients were Buffalo Soldiers. The remaining recipients were Black Seminole scouted on the plains and in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

In 1898, the four Black Infantry regiments were sent to Cuba to fight in the Spanish-American War and they also would serve Philippines. From 1903 to 1916, the 9th U.S. Calvary and 10th U.S. Calvary would perform their duty within the National Park Service, most notably in California, and under former Buffalo Soldier and Officer, 2nd Lieutenant Charles Young.

The Buffalo Soldiers would serve in World War I, World War II and the Korean War. There are powerful exhibits at the Buffalo Soldier National Museum, including the Civil War; Artillery; World War I and World War II and even a Tech Wall. These exhibits allow visitors to understand and respect the trials and triumphs these Black soldiers experienced in serving America. In 1953, the U.S. Army integrated its units and the Buffalo Soldiers would soon fade, for many, from history.

However, as you will learn at the BSNM, members of the 9th and 10th U.S. Calvary organized to honor their own rich legacy. General Colin Powell, who was the first Black four-star general of the United States and the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the highest collective in the U.S. military, was responsible for a bronze sculpture of a Buffalo Soldier being created and erected at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Powell, as Flanagan quoted, stated in the dedication, “Look at him, Soldier of the Nation … courageous, iron-willed, every bit the soldier that his White brother was … African-Americans had answered the country’s every call” and never received “the fame and fortune that they deserved …The Buffalo Soldier believed that hatred and bigotry and prejudice could not defeat him, that … someday, through his efforts and the efforts of others to follow, future generations would know full freedom.”

The first Buffalo Soldiers Day was July 28, 1992, when the monument to the Buffalo Soldier was dedicated at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas by General Powell. July 28th commemorates the formation, in 1866, of the first regular Army regiments comprising African-American soldiers.

The exceeding courage, honor, valor, and distinction that the Buffalo Soldiers showed in a field dominated by Whites and their perseverance despite endemic racism and prejudice has caused them to be honored in many forms of tribute. These forms include songs such as “Buffalo Soldier” by Bob Marley; in films like Sergeant Rutledge (1960), Joshua (1976), Buffalo Soldiers (1997) and Miracle at St. Anna (2008); U.S. postal stamps; nationwide chapters of a motorcycle club; monuments; books; and of course, the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum.

When you are in Houston, be sure to visit the Museum to learn more about these phenomenal Black men who were integral in developing our United States!