“Through her guidance of the Independent Order of St. Luke, Walker demonstrated that African American men and women could be leaders in business, politics, and education during a time when society insisted on the contrary.”

~ National Park Service

On July 15, 1864 in Richmond, Virginia, Elizabeth Draper gave birth to baby girl that she named Maggie Lena. Elizabeth, who was had been previously enslaved, worked as an assistant cook in the home of abolitionist and philanthropist Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew, a Unionist, is best known for her development of one of the most extensive spy rings against the Confederacy. It was at Van Lew’s estate in Church Hill where Elizabeth met Eccles Cuthbert, an Irish American who also hailed from Virginia. Cuthbert, a reporter for the New York Herald, was the father of Maggie; the two never married.

When Maggie was four years old, Elizabeth married William Mitchell, who also worked at the Van Lew mansion as a butler. Her stepfather’s surname would be given to her and Maggie Draper would be known as Maggie Mitchell. In 1870, the Mitchell couple welcomed a baby boy, who they named Johnnie.

William gained a position as the headwaiter at the premier Saint Charles Hotel. Their access to greater prosperity allowed him to move his family to a house in College Alley, not far from Van Lew, the Medical College of Virginia and First African Baptist Church. It was at First African Baptist Church where she was baptized and an active lifelong member. Sadly, in 1876, the body of William Mitchell was found, having been drowned in the James River. Though authorities cited the cause of death of suicide, Elizabeth vehemently denied their allegations, asserting that William had been murdered.

Elizabeth, now the sole provider for Maggie and Johnnie, made available her services as a laundress. A young Maggie assisted her and it was in her delivery of clean laundry that she readily discerned the pervasive and obvious cultural, educational, economic and social disparity between Blacks and Whites. This epiphany would be a guiding influence upon her for the remainder of her life. Decades later, Maggie would share, “I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but with a laundry basket practically on my head.”

Industrious and bright, Maggie Mitchell excelled in school. Honoring the values of education, she was fortunate to matriculate the Lancasterian School, Navy Hill School and Richmond Colored Normal School, all public schools for African-Americans. In 1883, she graduated from Richmond Colored Normal School, where she earned her credentials to teach. She returned to the Lancasterian School, where she taught and was also highly active in the Richmond community.

One organization in particular which would greatly benefit from Maggie Mitchell’s involvement was the Independent Order of Saint Luke. Founded in 1869, it was an African-American fraternal society devoted to the progress, via economics and culture, of the Black community. It also promoted cooperation, unity and self-help as well as assisted those in need, including children, the infirmed and elderly. A seventeen-year old Mitchell joined the Order in 1881 when she was enrolled at the Richmond Colored Normal School. That same year, she, according to her biography at Encyclopedia Virginia, also “organizes a Black student school strike to protest the inequality of White and Black graduation ceremonies.”

The Independent Order of Saint Luke was formed after a collective of members in the United Order of Saint Luke left due to differing views. The United Order of Saint Luke was founded by Mary Prout in 1867. Based in Baltimore, Maryland, it was a mutual aid and burial society. Originally open exclusively to women, the United Order later admitted men, one of those being William M.T. Forrester. Forrester would lead the Independent Order of Saint Luke for three decades.

Maggie Mitchell held various ranks in the Order while she taught. During this time, she was being courted by Armstead Walker, who worked in his family’s bricklaying and construction business. On September 14, 1886, they were married. Due to her new marital status, however, she was forced to quit her teaching position because the school forbade employment of married women.

Fortunately, Armstead was successful as a bricklayer and afforded her, now a homemaker, the opportunity to continue her work at the Independent Order of Saint Luke. This also was highly beneficial with the births of their children. They would have three sons: Russell Eccles Talmadge; Armstead Mitchell, who passed away at only seven months old; and Melvin DeWitt. They also adopted a daughter, Margaret “Polly” Anderson.

By 1895, Maggie L. Walker, as she had become known, was acting as the Grand Deputy Matron and her outreach was centered upon the youth. She created a division devoted to them and it stressed the values of education, community service and social consciousness, as Walker understood them as the future of the Black community. Emphasizing her vision, it is written in the Encyclopedia Virginia that “To underscore her belief that the future success of the order and of society itself came from investing in youth, Walker adopted the maxim: ‘As the twig is bent, the tree is inclined.’”

(No copyright infringement is intended).

In 1899, Walker ascended to the position of Right Worthy Grand Secretary of the Independent Order of Saint Luke. She held this position, the order’s highest rank, until her passing. By this time, unfortunately, the organization was practically bankrupt. She replaced Forrester who had forsaken his position and the organization due to its financial status. Fortunately, the purpose, passion, dedication and brilliance of Maggie L. Walker propelled her to not only save the Order but enhance it beyond any of its prior outreach.

Highly engaged during her sixteen-year involvement within the organization, she was innovative and creative. Committed, Encyclopedia Virginia reported that “she devoted the rest of her life to building membership and resources, expanding activities in business and social service, and keeping the financial operations efficient. Under Walker’s guidance, the Independent Order of Saint Luke’s fortunes were completely reversed. Although she inherited the Order deep in deficit, over the twenty-five years of her leadership it collected nearly $3,500,000, claimed 100,000 members in twenty-four states, and built up almost $100,000 in reserve.”

(No copyright infringement is intended).

In 1901 at a conference of the Independent Order of Saint Luke, Maggie L. Walker outlined and detailed her plans to further develop it to prosperity. It was a three-prong plan that allowed for the creation of their own newspaper, bank and department store in order to progress the Black community. With these three enterprises, the Black community would have greater possibilities of becoming independent, economically, socially and progressively, for years to come.

Within five years, she led the manifestation of all three into existence. In 1902, the St. Luke Herald began being published; its purpose was to share the work and accomplishments of the Order and assist in their efforts of education.

In 1903, the Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank began its operation, managed and maintained by members of the Order. Leading this financial institution, Maggie L. Walker became the first African-American woman to both charter a bank as well as serve as a bank president in the United States!

Youth were encouraged to open their own bank accounts in order to become economically independent. Walker believed in and promoted gender equality; as such, several Black women sat on the board of Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank. Walker, who acted as president until 1929, served as Chairman of the Board of Directors when she merged her bank with two other banks in Richmond. This merge led to the creation of The Consolidated Bank and Trust Company.

Successfully surviving the Great Depression, the bank would lead to the enduring stability, which included home ownership, of the Black middle class. As shared in the profile on Maggie L. Walker at Biography.com, “By 1924, under Walker’s continued leadership, the bank served a membership of more than 50,000 in 1,500 local chapters.” Her vision proved to be prescient, as this bank, according to the biography on Walker by the National Park Service, “thrived as the oldest, continually African American-operated bank in the United States” until 2009.

Her wisdom and efficacy in planning was essential when she co-organized the boycott of the Virginia Passenger and Power Company in 1904. Their highly successful protest against the company’s segregated seating in Richmond’s streetcars led to the company’s closing its doors within the year.

In 1905, the Saint Luke Emporium opened its doors. It provided employment to African-Americans, especially women, and access to quality goods at affordable prices. Championing the respect that should be afforded Black consumers, Walker refused to shop where Blacks were told to use the back and side doors or be forced to wait after Whites in order to be serviced. Unfortunately, White retailers’ backlash and some Blacks’ fear of retaliation for shopping at the Order’s store ultimately led to the Emporium closing in 1911.

The year prior to the launch of the Order’s department store, the Walkers moved to a new family home at 110 ½ East Leigh Street. Located in the Jackson Ward neighborhood of Richmond, it was bustling with successful Black business and vibrant with Black cultural self-determination. It carried a glowing reputation for Black upward mobility. Historically, according to the National Park Service website, the community of “Jackson Ward is known as the birthplace of African-American entrepreneurship (‘The Cradle of Black Capitalism’) and is one of the largest (42 city blocks) national historic landmark districts associated with African American history and culture in the United States.”

(No copyright infringement is intended).

Additionally, its educational, economic and social progress and promotion of Black arts, literature, music and political empowerment prompted Jackson Ward to be hailed as the “Harlem of the South”. The home of the Armstead and Maggie L. Walker family would expand over time, growing from its original nine rooms to a staggering twenty-eight. This expansion was made to accommodate spaces for their children and the families they created.

Despite these successes, tragedy would visit Maggie L. Walker again. In 1915, her husband, Armstead, was accidently shot and killed by their son, Russell; they were looking for an intruder in their home. Arrested for murder, he was found innocent. Yet Russell never recovered from the accident and after suffering alcoholism and depression for eight years, he died in 1923.

By this time, the health of Walker, who had suffered from diabetes, begin to wane. She endured a wound that never healed. By 1928, paralysis caused her to spend the remainder of her life having to use a wheelchair.

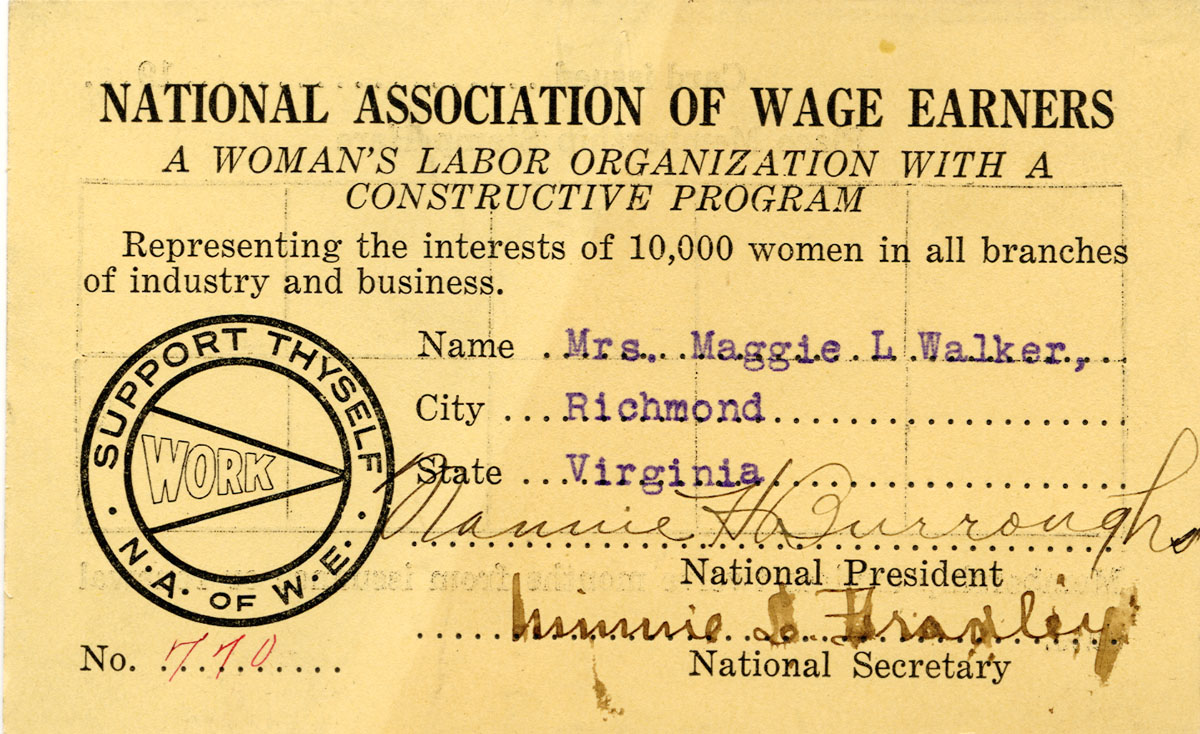

These tragedies did not deter her from her work. She remained active in civic groups, including the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), the Virginia Industrial School for Girls and the Virginia Interracial Commission. Walker co-founded and served as the vice president of the Richmond chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and sat on the civil rights organization’s national board.

Maggie L. Walker was even involved in politics. In 1921, she, as a member of the “Black Lily”, an all-Black faction of the Republican Party, ran for the office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Her running mate was John Mitchell, editor and publisher of the Richmond Planet; he was on the ticket for the office of governor. No one in the Black Lily won the office they were seeking. A determined Walker continued to advocate for the Black community, strongly supporting education for Black girls and the anti-lynching movement.

On December 15, 1934, Maggie L. Walker passed away due to diabetic gangrene; she was seventy years old. Her largely-attended funeral was held at First African Baptist Church and she was buried at Evergreen Cemetery.

Walker received many accolades in her lifetime, including an honorary Master of Science degree from Virginia Union University in 1925 and induction, as an honorary member, of Zeta Phi Beta, an African-American sorority. Posthumously, she, in 2000, became a member of the inaugural class honored as “Virginia Women in History” by the Virginia Foundation for Women and Delta Kappa Gamma. She was inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 2001.

Also in 2001, the Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School for Government and International Studies opened. Its former use was the Maggie L. Walker High School, where generations of African-Americans were educated. The public, secondary school has been recognized nationally for its academic excellence.

In 1975, the home of Maggie L. Walker was added to the Virginia Landmarks Register and the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as well as designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The following year, it was designated as a U.S. National Historic Landmark District Contributing Property. In 1978, the home was designated a U.S. National Historic Site. In 1979, the U.S. National Park Service bought the Walker home from Maggie L. Walker, the granddaughter of Maggie L. Walker.

(No copyright infringement is intended).

After restoration and renovation, the NPS made it available, as a museum, to the public in 1985. Its design and décor remain true to how it looked when the Walker family lived there during the 1930s and includes their items.

The Saint Luke Building, which housed the headquarters of the Independent Order of Saint Luke, was installed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. Inside is Walker’s office, which has been preserved to appear as it was when she worked there.

(No copyright infringement is intended)).

A 10-foot, bronze statue of Maggie L. Walker was installed in Maggie L. Walker Plaza on Broad Street in Richmond in 2017. Sculpted by Antonio Tobias Mendez, it features a checkbook in her left hand and a pair of eyeglasses pinned to the lapel of her dress. Mendez is the son of CIA spy-turned sculptor Tony Mendez. It seems a bit ironic that he would sculpt Maggie L. Walker, whose mother, Elizabeth, worked for Elizabeth Van Lew, mastermind of one of the greatest spy rings in the United States.

However, what really cinched his opportunity to sculpt Walker was his prior work that honored both leaders in advancing civil rights, such as Mohandas Gandhi, as well as accomplished African-American achievers, including biologist Ernest Everett Just, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and cyclist Major Taylor. In “The First Woman to Start a Bank – a Black Woman – Finally Gets Her Due in the Confederacy’s Capital” By Michael S. Rosenwald in The Washington Post, Mendez shared his insight and hope that in the near future, there will be more bronze statues honoring not just African-American men but women, like Maggie L. Walker, too. He affirmed, “These places bring people together … They tell stories that should be told.”

In 2020, Maggie L. Walker became one of eight women highlighted in “The Only One in the Room” display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Her inclusion represents her lifelong commitment to attain gender and racial equality via community service, economics, education, entrepreneurship, politics and social mobility.

“Let us put our moneys together … Let us use our moneys; let us put our money out at usury among ourselves and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

~ Maggie L. Walker