“Earl Graves was a catalyst for change and progress in the African American community … He also provided a bridge from the African American community to the larger White corporate community. He challenged the status quo. And he sought to make the powers and institutions accountable for the neglect African Americans received over the previous 400 years.”

~ Rev. Franklyn Richardson, pastor, Grace Baptist Church, Mount Vernon, New York

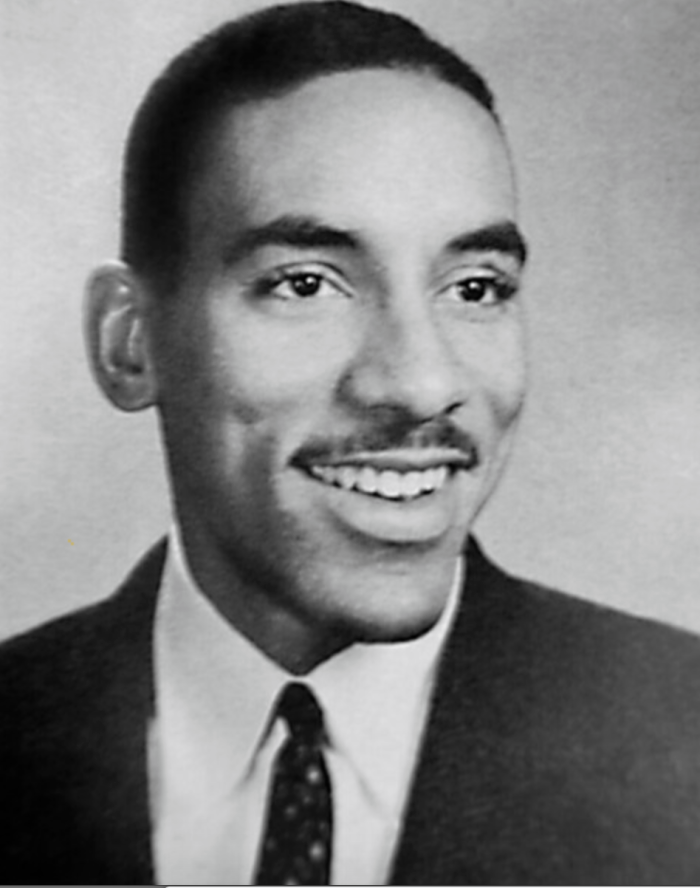

A baby boy was born to Earl Godwin and Winifred (née Sealy) Graves on January 9, 1935 in the Brooklyn borough of New York City. They named him “Earl”, after the father, and retained the “G” initial but named him “Gilbert”. From an early age, the son learned the values of creativity, determination, dedication and initiative from his parents who had emigrated from the West Indies. Being reared in the close-knit community of Bedford-Stuyvesant, he sold for his uncle boxes of Christmas cards to neighbors when he was just seven years old. Though limited by his father’s stern directive that he could not cross the block, this was Earl’s early advent in entrepreneurship, which became a lifelong passion.

Bright and outgoing, Earl G. Graves matriculated Morgan State University, a historically Black institution of higher learning in Baltimore, Maryland. While there, he noted the dearth of flowers during a Homecoming Weekend. To eliminate this absence, he devised a novel plan with two different florists to sell flowers on the campus during this festive time of celebration.

(No copyright infringement intended).

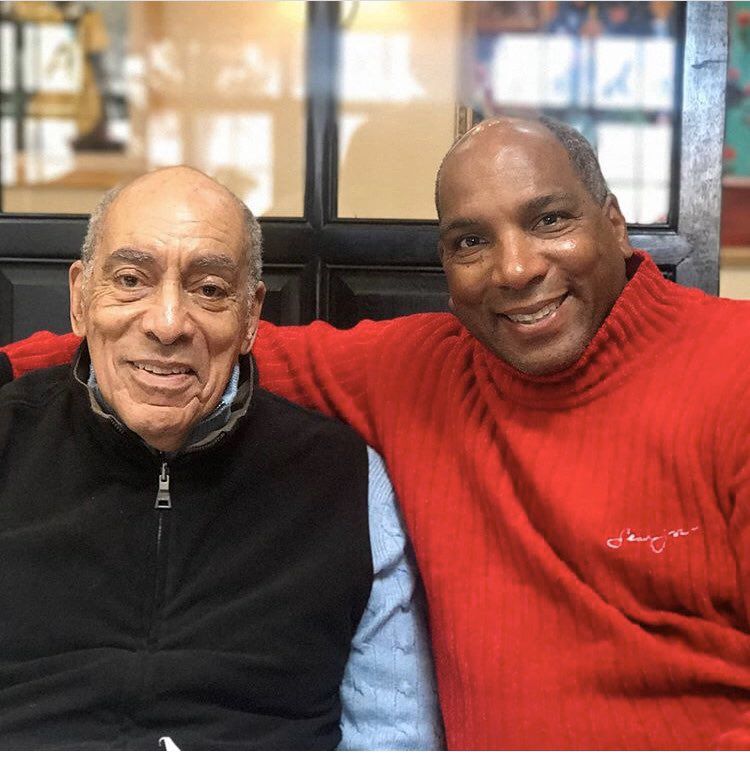

A member of the Reserves Officers’ Training Corp (ROTC) and Omega Psi Phi fraternity, Earl G. Graves graduated with his Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics in 1958. After completing his degree at Morgan State University, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he attended its Airborne School and Ranger School. He served two years as an officer and achieved the rank of captain. Upon completion of his term of service, he then held various positions in law enforcement, real estate, and as national commissioner of scouting for Boy Scouts of America. It was during these years that Earl G. Graves courted Barbara Kydd, who he married in 1960. They would have three sons: Earl Jr., known as “Butch”, John and Michael.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

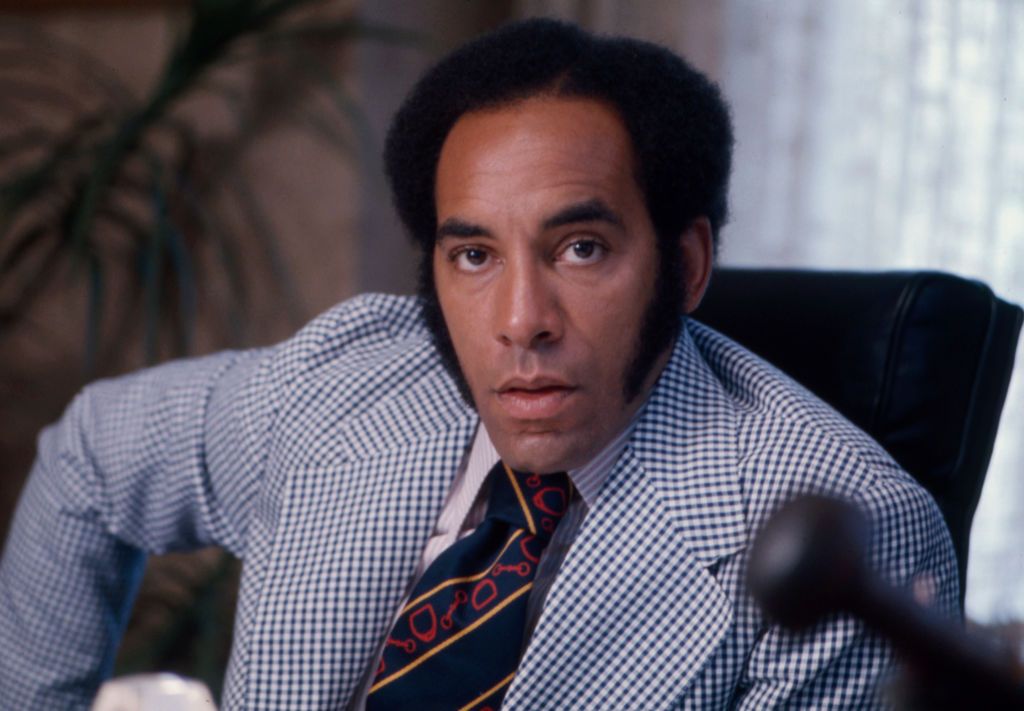

Highly interested in the advancement of the Black community and political engagement, Graves became a volunteer for the 1964 presidential campaign of Lyndon B. Johnson. Active within the Democratic Party, significantly its National Committee, he, in 1965, acted as the administrative assistant to U.S. Senator Robert Kennedy (D-NY). He worked with Kennedy for three years and, sadly, was at The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California when the senator was tragically assassinated on June 6, 1968.

That year, Graves then transitioned to working within the Small Business Administration, having gained a seat on its advisory board. During this time, he created his own company, consulting corporations on economic development and urban affairs, focusing especially on those regarding the African-American community. His tenure with the Administration further strengthened his understanding that many Blacks needed not just professional advice to successfully attain careers as well as develop networks but also personal insight to navigate corporate America, protect wealth and promote financial security for present and future generations.

(No copyright infringement intended).

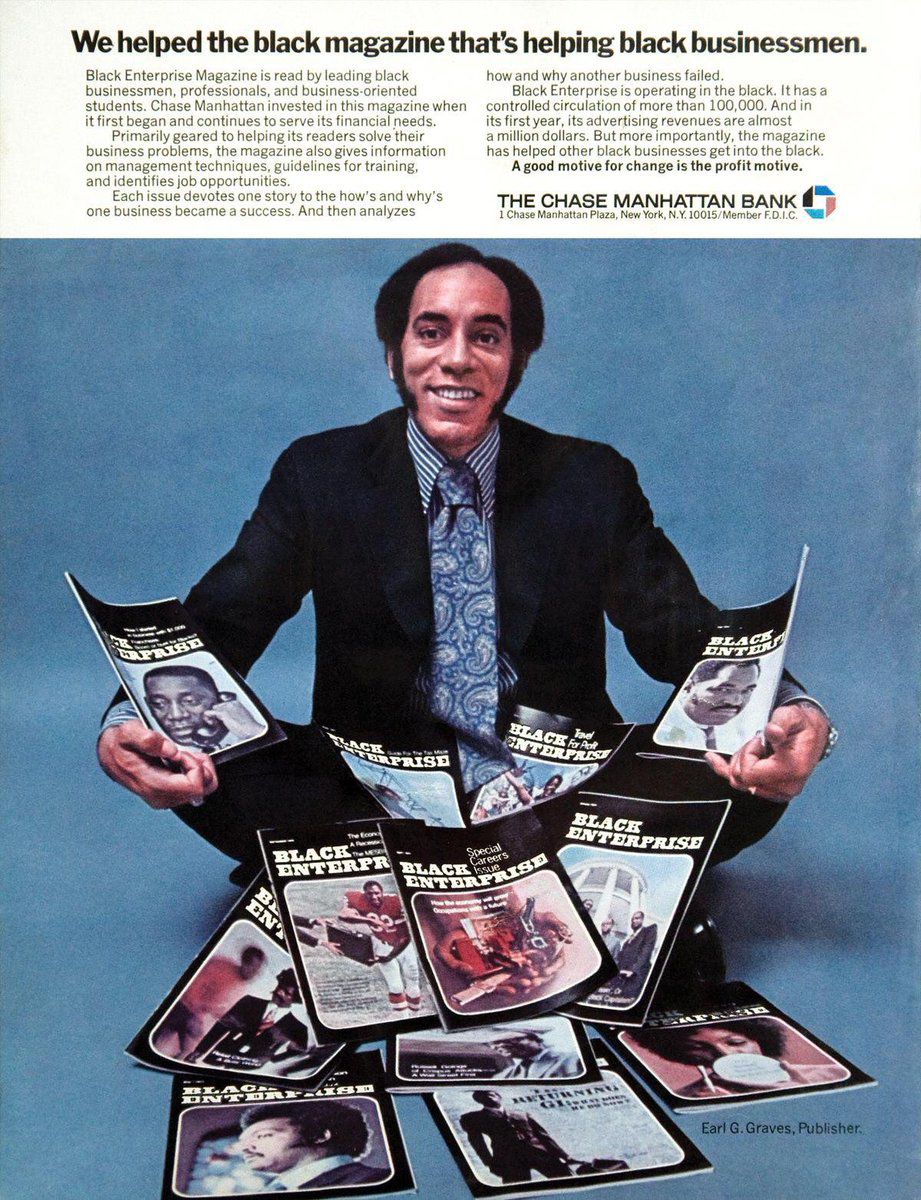

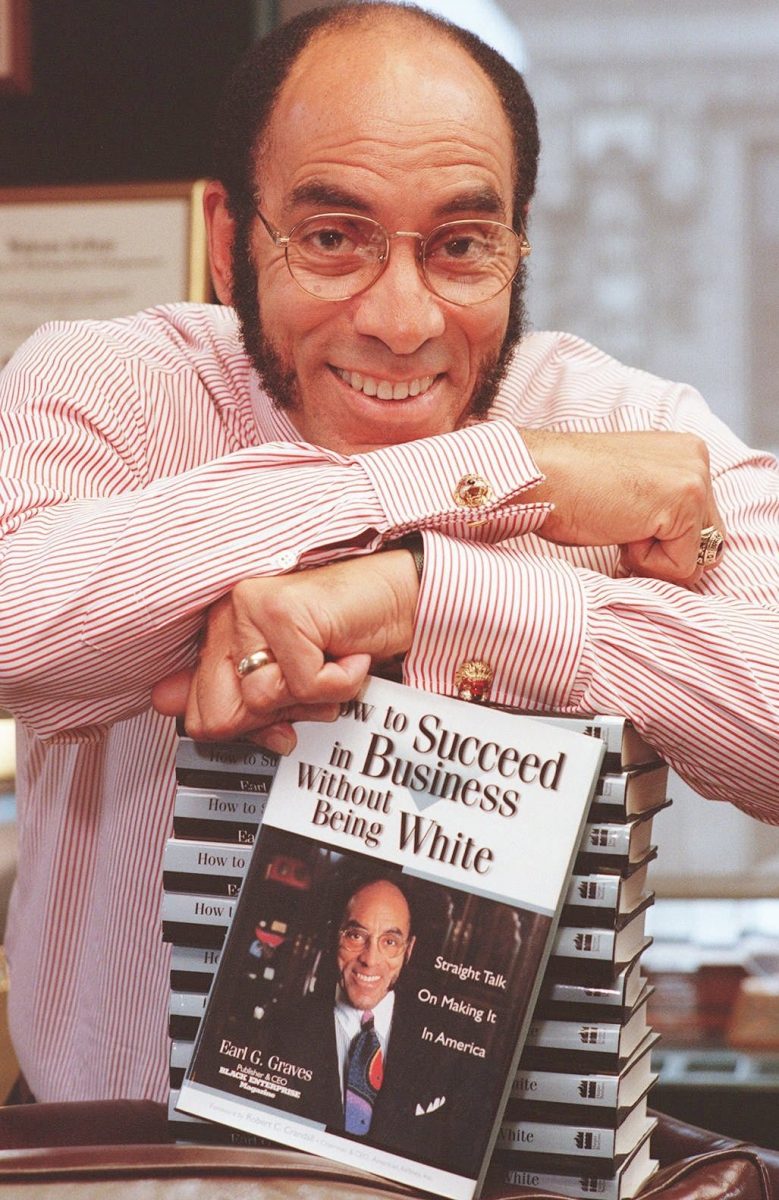

Accordingly, he created a newsletter that manifested in a magazine, Black Enterprise. Launched in 1970, this periodical was essentially a blueprint for Black entrepreneurship. It sought to create positive spheres of influence for Black-owned businesses within private and government institutions and organizations. Serving as its editor, Earl G. Graves, according to “Earl Graves, Sr., Founder of Black Enterprise, Passes Away at 85”, by Derek T. Dingle on the website of Black Enterprise, reflected on the founding of Black Enterprise. In the article, the magazine founder had shared in his How to Succeed in Business Without Being White (1997), that “The time was ripe for a magazine devoted to economic development in the African American community. The publication was committed to the task of educating, inspiring and uplifting its readers. My goal was to show them how to thrive professionally, economically and as proactive, empowered citizens.” Graves’ book ranked high on the best-sellers list of The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal.

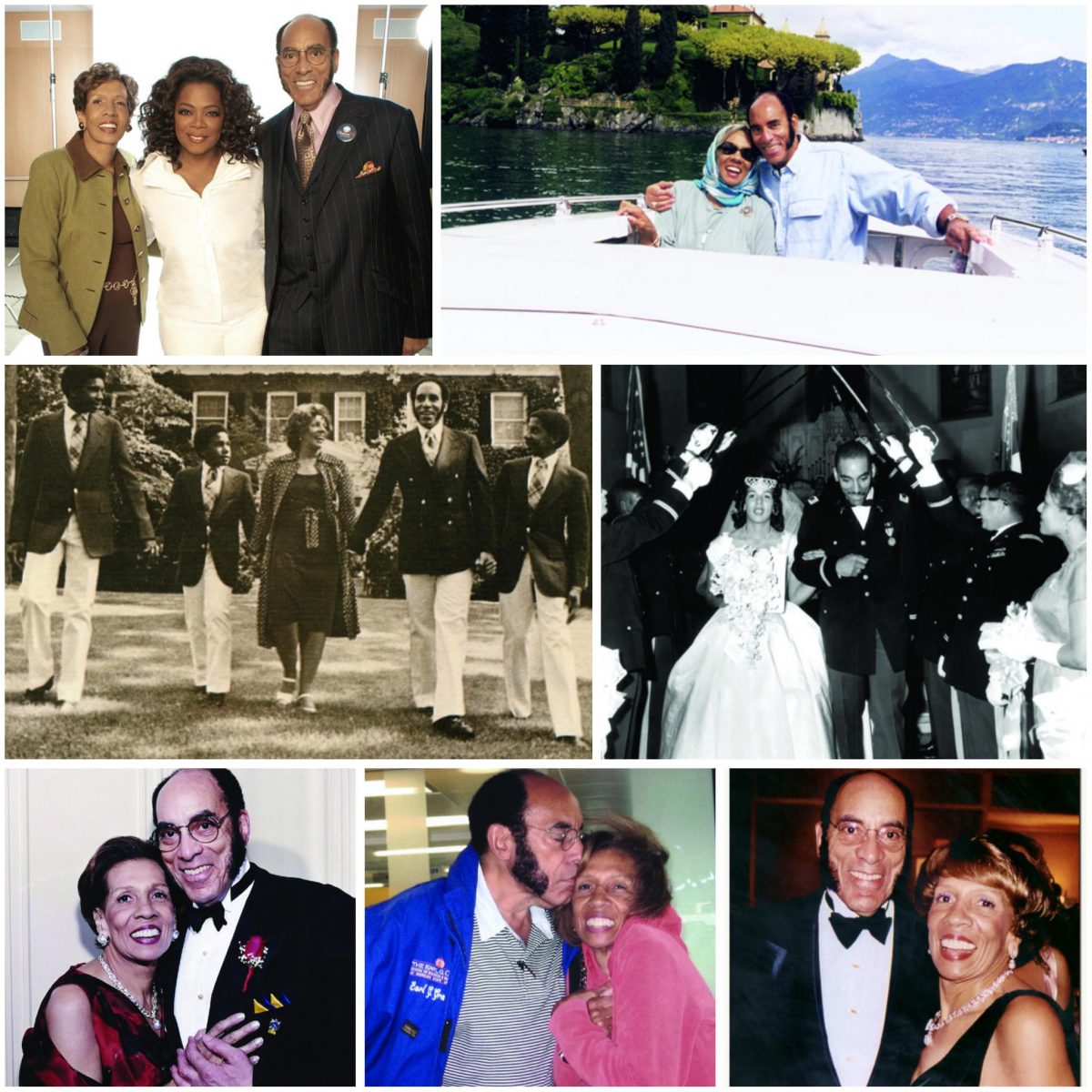

His work in developing Black Enterprise would not have been possible without his wife, Barbara Kydd Graves. In the Dingle article, he proudly affirmed that “Black Enterprise was just a modest magazine when I founded it — just me, a few brave advertisers like Pepsi, ExxonMobil and General Motors; and a small but spirited staff. And one other person who did just about everything there is to do to put out a magazine — my wife, Barbara.” All involved worked diligently and the publication was so successful that Graves was able to repay its $250, 000 loan from Chase Bank within ten months!

(No copyright infringement intended).

Black Enterprise grew over the next five decades to become a multi-media empire that educates its audience on the power, as written by Dingle, “of financial empowerment to more than 6 million African Americans through print, digital, broadcast and live-event platforms.” One of the tools Graves created to highlight Black entrepreneurship was the “Black Enterprise 100”, also called the “BE 100”. Each year, the magazine profiled the top one hundred, Black-owned industrial and service businesses in the United States. This measure promoted, further supported and celebrated Black business excellence. Premier in its mission and drive, it is no surprise that Black Enterprise, as emphasized by Dingle, “was one of only two companies that would appear on the BE 100 — the publication’s annual rankings of the nation’s largest Black-owned businesses — each of its 47 years. At one point, Graves would operate two companies on the list, including Pepsi-Cola of Washington, DC, one of the nation’s largest soft-drink distributors owned by African Americans.” Graves, according to his biography on The HistoryMakers website, was also a general partner of Egoli Beverages, L.P., the Pepsi-Cola franchise bottler of South Africa.

Earl G. Graves conducted a brilliant business coup in 1990 when he bought the rights for the distribution operations of Pepsi-Cola in Washington D.C. Graves served as the chief executive officer and chairman. He partnered with Ervin “Magic” Johnson, star of the Los Angeles Lakers and entrepreneur, who acted as executive vice-president and spokesperson. According to the biography on Earl G. Graves at Encyclopedia.com, ownership of “the franchise, which distributes over four million cases of Pepsi annually in the District of Columbia and parts of Maryland, has been estimated to be worth about $60 million and makes Graves and Johnson Pepsi’s largest minority franchisees.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Under Graves’ and Johnson’s leadership, the Pepsi-Cola distributorship won “Bottler of the Year” award three times. In 1998, they sold the Pepsi franchise, which covered 400 square miles. For certain, Graves, an astute businessman, received an offer that he felt was fair but also accepted to remain working on a national level with the soda pop manufacturer. Centered around marketing and sales, Graves accepted the position of Chairman of Customer Advisory and Ethnic Marketing Committee. He guided management at Pepsi in their business practices and professional relationships with their ethnic consumers.

He served as the chief executive officer and president of Earl G. Graves, Ltd., which was the parent company of Earl G. Graves Publishing Company. Under the publishing company’s imprint was Black Enterprise as well as best-selling books on Black entrepreneurship. He also created and led Black Enterprise Unlimited, the sister company of the publishing company; Earl G. Graves Marketing and Research Company, Earl G. Graves Development Company and EGG Dallas Broadcasting Company. Always a visionary, Graves created in 1998 the “Kidpreneur Konference” and formed the Black Enterprise/Greenwich Street Growth Partners. The former was to educate and encourage African-American youth in their involvement in entrepreneurship. The latter, according to the Graves biography at Encyclopedia.com, was a “private equity fund [that] was created to help minority and women controlled businesses with a minimum annual revenue of $10 million.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Expanding beyond his business interests, Earl G. Graves was active in civil rights, philanthropy and politics. He used his immense influence to gain support for the election of Senator Barack H. Obama (D-IL) to become the first African American president of the United States. Graves’ means included endorsing Obama in Black Enterprise and acting as a surrogate, campaigning on the Chicago politician’s behalf.

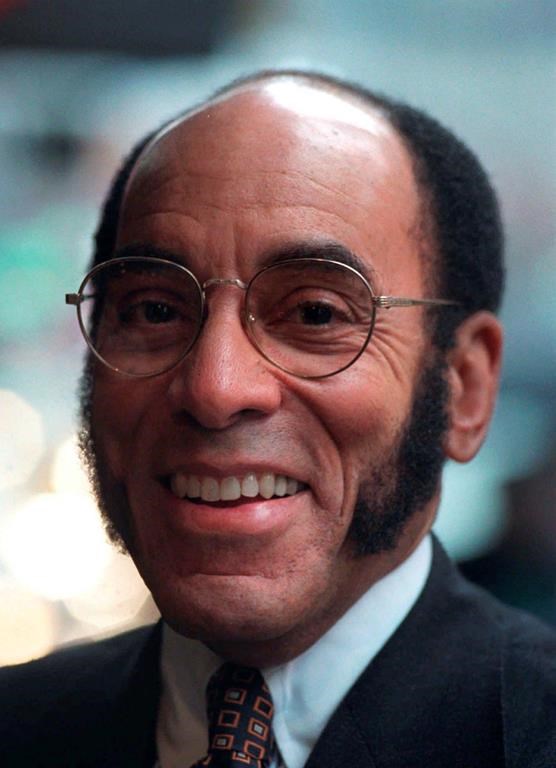

For his many contributions to the betterment of the Black community and society, Earl G. Graves has received numerous honors. These include the National Award of Excellence given by the U.S. Department of Commerce in 1972; being one of the “Ten Most Outstanding Minority Businessmen in the United States” by President Richard M. Nixon in 1973; Outstanding Citizen of the Year” by Omega Psi Phi in 1974; and a Poynter Fellow by Yale University in 1974. Named an “Outstanding Black Businessman” by the National Business League, Graves sat on a number of boards of directors, including that of the Chrysler Corporation and New York State Urban Development Corporation. He has also served as Chairman of the Board for the Black Business Council.

He was a dedicated supporter of institutions, including his alma mater, Morgan State University, and organizations such as the United Way and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1995, Graves donated $1 million dollars to the university; in gratitude, its business school was renamed the “Earl G. Graves School of Business and Management”. The donation was to further develop the School and greater ensure successful African-American entrepreneurship.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Four years later, Earl G. Graves was gifted the Spingarn Medal, the highest award given by the NAACP. Created in 1914, it honors achievement and merit of African-Americans. Graves was gifted this medal during the 90th anniversary of the civil rights organization. It was awarded in 1999 by the president and chief executive officer of the NAACP, Kweisi Mfume. Mfume, as printed by Jet, praised Earl G. Graves “for his success as a businessman, publisher, dedicated advocate of education, passionate crusader for civil and human rights, conscientious civic leader, groundbreaking entrepreneur, and devoted family man.” At this anniversary, Graves’ shared his gratitude and generosity. He detailed that he and other Black business leaders had created the “Earl G. Graves/NAACP Scholarship Fund”. Pledging 1.23 millions dollars, Graves informed the guests that “The scholarship fund will be a vehicle to help others to dream and to succeed.”

The Miami Times

(No copyright infringement intended)

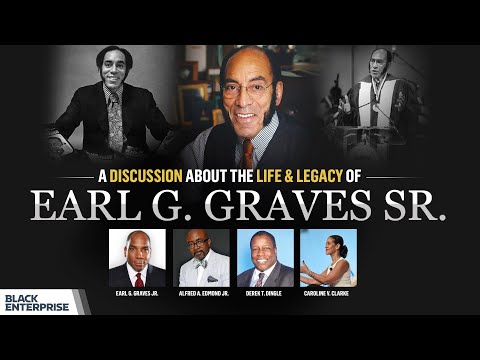

On April 6, 2020, Earl G. Graves, who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, passed away; he was eighty-five years old. He was preceded in death by his wife, Barbara, who died in 2012.

His rich and extensive legacy includes countless people he guided, mentored and championed. This sentiment was echoed in “Founder of Black Enterprise Magazine; Chairman of Earl G. Graves Ltd.” on the website of Babson College, which proclaimed “the finest and most lasting tribute to Graves’ economic, political and social influence may be the fact that the gross sales of the Black Enterprise 100 companies has increased from less than $450 million in 1970 to more than $9 billion today. The owners and managers of many of these companies would be the first to tell you how much of their success is due to Earl G. Graves.”

Though incredibly accomplished, Earl G. Graves remained grounded. As Dingle quoted the African-American trailblazer who affirmed, “The truth of the matter is that we are humbled by the achievements of the talented people we report on … We are in awe, still, by the courage it takes to put oneself on the line in an unmerciful marketplace.”

“I think we’ve been the drum major in this country for Black business and for Black professionals. We’ve been able to show that, when given the opportunity, Black people can be as good as anybody, and in many cases, better.”

~ Earl G. Graves