“While we may have faced challenges on the bench, when Connie lifted her voice, her life was on the line … Yet time and time again, she lifted her voice higher and higher, arguing cases in hostile towns, against hostile lawyers, and before hostile judges in the pursuit of equal justice.”

~ Ann Claire Williams, retired justice, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

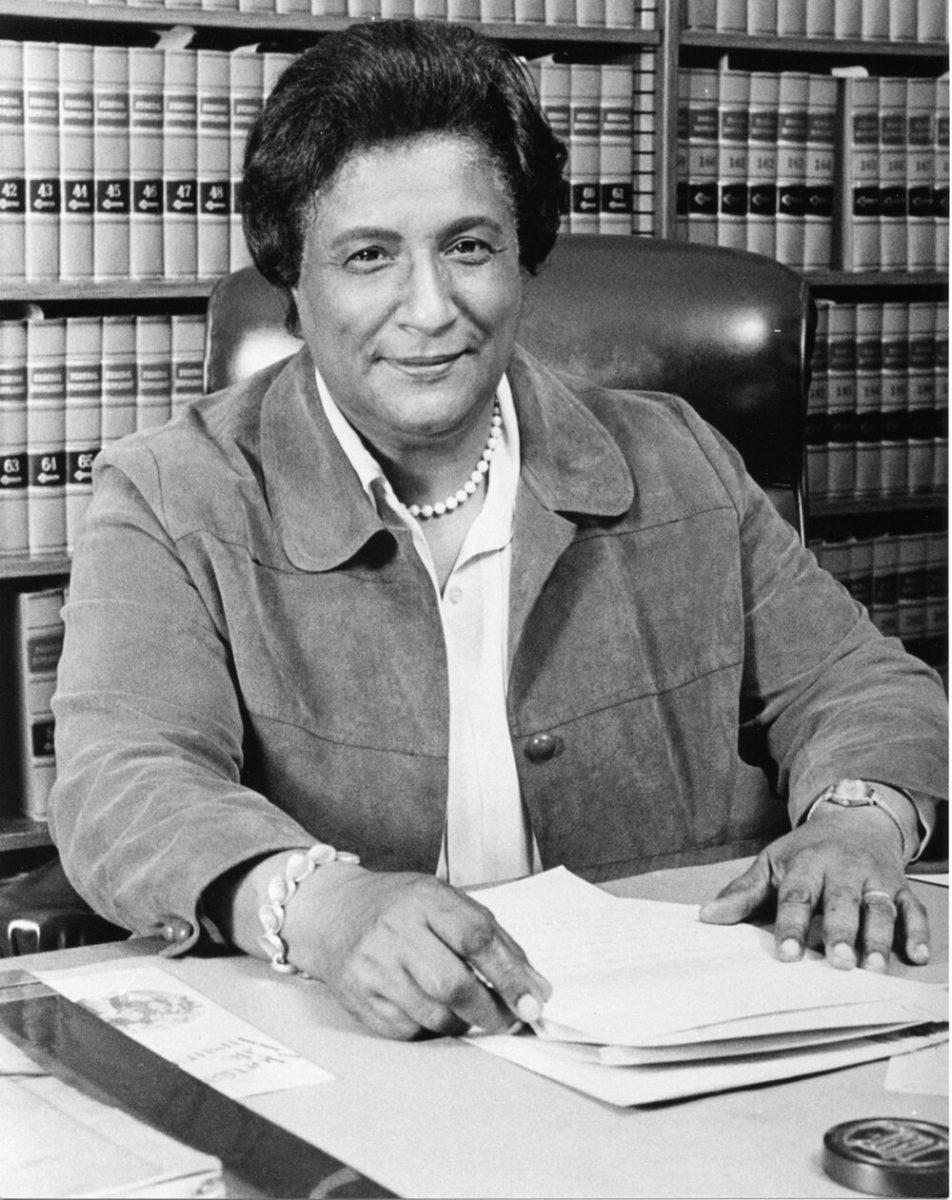

On September 14, 1921 in New Haven, Connecticut, Nevisian parents McCullough and Rachel Baker welcomed a baby girl. Naming her “Constance”, she would be the ninth of the Caribbean couple’s ten children. Immigrants, the Bakers worked in fields all too often reserved for Blacks at that time. Rachel labored as a domestic worker and McCullough worked as a chef for various societies, including the elite and exclusive Skull and Bones, at Yale University.

As a little girl, Constance experienced Black culture. These experiences range from learning African American history to seeing activism modeled by her mother, a co-founder of the New Haven chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She joined this branch when she was forbidden entry into a skating rink and onto a public beach.

Her childhood, overall, was primarily free of racial discrimination. It was not until she was on a train ride to Tennessee that she first encountered racism, becoming acutely aware of the Jim Crow laws. In her 1998 autobiography, Equal Justice Under Law, Baker Motley referenced this epiphany, centered upon her arrival in Cincinnati, Ohio. She was forced to ride in an antiquated and dilapidated car designated “Colored” for African-Americans. She emphasized, “Although I had known this would happen, I was both frightened and humiliated. All I knew for sure was that I could do nothing about this new reality.”

Extremely bright and pro-active, Constance Baker excelled in learning. While in Hillhouse High School, she served as president of the New Haven Youth Council and was secretary of the New Haven Adult Community Council. After graduating with honors in 1939, she continued to work within the community, including with the National Youth Administration. Although the Baker family lacked the economic resources to attend a university, her dreams to become an attorney were realized with the aid of New Haven businessman, Clarence W. Blakeslee. Also a philanthropist, Blakeslee first became acquainted with Constance when he heard her speak at a local community center. Thoroughly impressed, he asked her of her plans for her future. After sharing her desire to become an attorney, Blakeslee offered to pay for Baker’s formal education.

Constance Baker first attended Fisk University, a prestigious, historically Black university in Nashville, Tennessee. However, she later returned to the East coast, matriculating New York University. There, she earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in 1943. She then entered Law School at Columbia University in the City of New York. During her time at Columbia Law School, she worked as a law clerk for Thurgood Marshall, attorney for the NAACP, who would become the first African-American to serve as a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. With Marshall, she assisted on cases dealing with court martials filed after World War II ended.

Three years after her entry into Columbia, she earned her Bachelor of Law degree. That same year, in 1946, Constance Baker and real estate and insurance broker Joel Motley, Jr. married at Saint Luke’s Episcopal Church in New Haven. They would have one son, Joel Wilson Motley III.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Upon her graduation from law school, Constance Baker Motley was hired to work as a civil rights attorney by the NAACP to work on its Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF). As the Fund’s first female lawyer, she served as its Associate Counsel, often acting as lead trial attorney in numerous cases. These cases involved her representation of and kinship with groups such as the Freedom Riders and the Birmingham Children Marchers and persons including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Medgar Evers.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In her autobiography, Baker Motley tragically recalled her visits with King in several jail cells and her advice to Evers to cut his tall hedges, where, later, his assassin hid. Her visits down South were met with threats of violence and due to segregation, she stayed with local activists in the communities in which her clients lived.

In 1950, she authored the original complaint filed in the historic Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Twelve years later, Constance Baker Motley became the first African-American woman to represent, on a federal court, her client when she argued Meredith v. Fair before the U.S. Supreme Court. With the support of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, Baker Motley won James Meredith’s racial discrimination case against the University of Mississippi. The enrollment of Meredith, the first Black student to attend the University of Mississippi, led to riots and the deaths of two persons on campus; federal troops were sent in to restore order.

She continued her work with the LDF, guiding in the legal de-segregation of public accommodations, such as buses, lunch counters, parks and schools. Constance Baker Motley argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, assisting in almost sixty cases and successfully winning nine of her ten cases!

(No copyright infringement intended).

She expanded her work in civil rights to become an elected official and in early 1964, she was elected to represent the 21st District of New York in the Senate. Initially, she attained this position because her predecessor, James Lopez Watson, had been elected to serve in the New York City Civil Court. Watson was the first African-American to head a federal court in the South. The election of Constance Baker Motley rendered her to be the first African-American woman to serve in the State Senate!

(No copyright infringement intended).

Representing the 174th New York State Legislature, she won the election held later that year and represented the 175th New York State Legislature. She resigned from this position and the Legal Defense and Educational Fund of the NAACP in 1965. She did these after accepting to become a borough president in New York City. The first woman to hold this position, Constance Baker Motley served as the Manhattan Borough President. Her work centered upon improving the quality of life for Black and Brown people in urban settings as well as supporting urban renewal projects including improvements in housing and schools.

In 1966, she was nominated by President Lyndon B. Johnson to a seat on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Her nomination was stalled seven months by racist, Southern conservatives in the Senate, notably James Eastland (D) of Mississippi. Eastland, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, vehemently opposed her because of her successful legal work, including in Brown v. Board and Meredith v. Fair. Known as the “Godfather of Mississippi Politics” and “The Voice of the White South”, Eastland was an icon of intense, Southern, White racism and resistance during the Civil Rights era. His attempts, which included accusing Baker Motley of being a Communist, proved futile. Her commission was approved. On August 30, 1966, Constance Baker Motley, the first African-American women to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, became the first African-American woman to serve as a federal judge!

(No copyright infringement intended).

She continued to work on behalf of those in the greatest need. Those persons included Vietnam War protestors in Belknap v. Leary, who Baker Motley ruled should have stronger protections by the New York Police Department and in Ludtke v. Kuhn, when she ruled that a female reporter must be allowed into a Major League Baseball locker room.

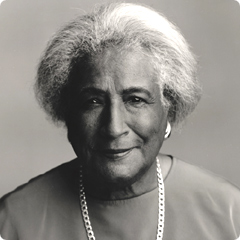

While on the bench, she befriended and mentored other women, significantly Black, attorneys and judges who followed her. These included Laura Taylor Swain, Anne Thompson and Ann Claire Williams. In 1982, Constance Baker Motley became Chief Judge. In 1986, she became Senior Judge and held this position for nineteen years, until her death.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On September 28, 2005, just two weeks after her birthday, Constance Baker Motley passed away from congestive heart failure at New York Downtown Hospital. She was eighty-four years old. Her funeral was held at Saint Luke’s Episcopal Church in New Haven, the church where she was married. There was a memorial, open to the public, held at Riverside Church in Manhattan.

(No copyright infringement intended).

She was the recipient of numerous accolades and honorary degrees, including a Candace Award by the National Coalition of 100 Black Woman in 1984, the Presidential Citizens Medal in 2001 by President Bill Clinton and the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP in 2003. Inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993, she was awarded posthumously the Congressional Gold Medal in 2006 by Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY) and Senator (D-NY) and First Lady Hillary Clinton and the Ford Freedom Award by Ford Motor Company in 2011.

In the recent past, she has not received the type of reverence as her contemporaries, including Marshall, with whom she worked, and King, Jr., who she legally represented. However, the hope that the stellar work and incredible accomplishments of Constance Baker Motley will enlighten and inspire many inside and outside the world of civil rights and law is immense. This hope becomes even more probable when persons, such as attorney and Vice-President Kamala Harris (D-CA) salute Constance Baker Motley as a primary influence on their career and lives!

“I was the kind of person who would not be put down … I rejected any notion that my race or sex would bar my success in life.”

~ Constance Baker Motley