“Of all the endeavors, Dr. Patterson’s starkest accomplishment remains the scope of the people he influenced. Over the course of his 87 years, he inspired Americans as well as African-Americans. He influenced higher education policy and practice. He changed the way that philanthropy would be conducted. He generated a dynamic that pushed every organization to its limit. Hundreds of thousands of Americans continue to feel the effects of Frederick D. Patterson’s work and dedication.”

~ The United Negro College Fund

On October 10, 1901 in Buena Vista Heights of Washington, D.C., William Ross and Mamie Lucille Patterson welcomed their son into their lives. The parents named him in honor of the incredible abolitionist, activist, author, orator and statesman, Frederick Douglass. Douglass, who lived just three blocks away at his home, Cedar Hill, also was a resident of the Anacostia neighborhood. Sadly, William and Mamie passed away from tuberculosis, rendering two-year old Frederick orphaned.

For the next several years, he was shuttled from the District to Texas, living between different relatives until his older sister, Bessie, took primary custody of him. The loss of his parents and lack of familial stability greatly impacted Frederick and, according to the biography on him at the United Negro College Fund website, “as late as the eighth grade, his classmates voted him less likely to succeed.”

Bessie strongly believed in education and sacrificed $8 of her $20 monthly pay to send Frederick to the private elementary school at Samuel Huston College (presently known as Huston-Tillotson College). His passion for learning, especially concerning animals and agriculture, ignited and he attended Prairie View Normal and Industrial Institute (known today as Prairie View A & M University) in Prairie View, Texas. The focus of his academic work was centered in the Agriculture Department and he studied under its top veterinarians, including his mentor, Dr. Edward B. Evans. Evans was key in influencing Patterson’s decision to further his studies at Iowa State College (now Iowa State University), Evans’ alma mater.

After earning his Bachelor of Science degree and a teaching certificate from Prairie View in 1915, he matriculated Iowa State College (ISC). In the next nine years, he excelled, earning three graduate degrees. In the field of veterinary medicine, Frederick D. Patterson was awarded his Doctorate in 1923 (he was only twenty-two years old!) and his Master of Science in 1927 from the College of Veterinary Medicine at ISC. He earned a Doctor of Philosophy in veterinary pathology from Cornell University in 1932.

Frederick D. Patterson worked at Virginia State College while he was enrolled in graduate school. From 1923 until 1928, he taught veterinary science and later served as the College’s Director of Agriculture. He then left for Alabama, where he became the head of the Veterinary Department, then the director of the School of Agriculture at Tuskegee Norman and Industrial Institute, currently known at Tuskegee University. Patterson’s leadership, genius, involvement and commitment to this historic Black institution for higher learning was so great that in 1935, he was appointed to be the college’s third president; Frederick D. Patterson was only three-three years old!

(No copyright infringement intended).

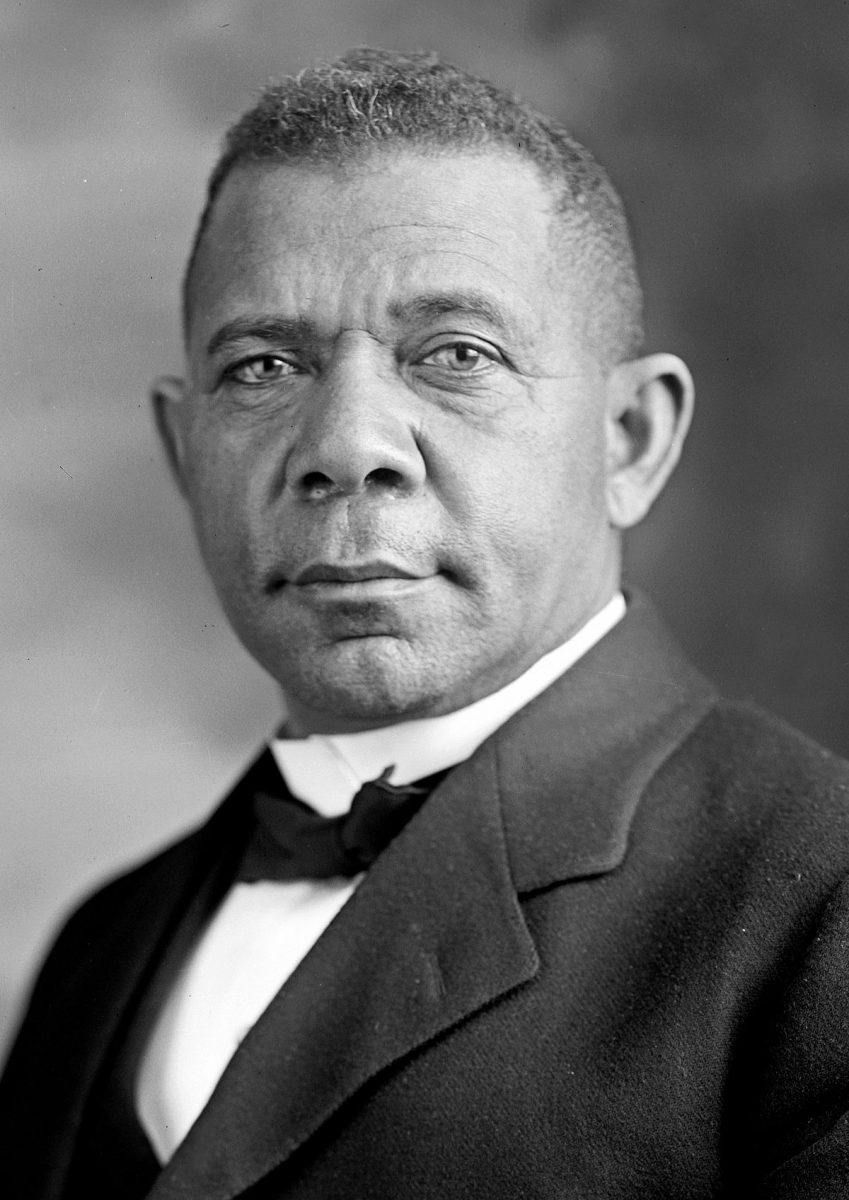

The first president of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute was its founder, twenty-three year old Booker T. Washington, and the second was Robert Russa Moton. Patterson served as the president of Tuskegee University for almost twenty years, from 1935 until 1953. The same year that he was appointed president, Frederick also married; his new wife was the former Catherine Elizabeth Moton, the daughter of his predecessor.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

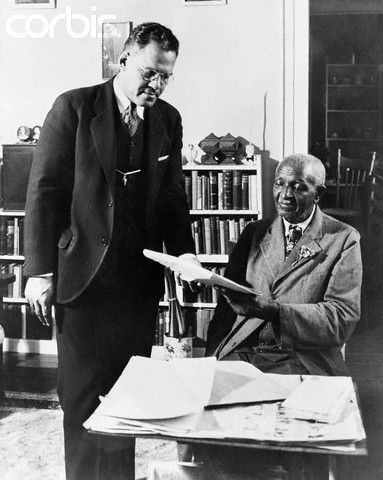

As head, Frederick D. Patterson enacted changes and launched initiatives that further increased the programs and outreach of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. In the UNCF biography, it is written that “Dr. Patterson transformed the baccalaureate institution into a prestigious university with cutting-edge graduate programs, all of which are flourishing today. He founded the commercial dietetics program, which infused professional cooking with business and service savvy and placed African American students in unprecedented high-level internships across the country. The veterinarian understandably took personal interest in the school’s veterinary medicine program, which afforded Southern African-Americans the only opportunity to become veterinarians in that region of the country. Tuskegee has graduated 75 percent of the nation’s African-American veterinarians. His foresight into emerging fields also prompted him to spearhead the engineering program, which from its inception enabled African-Americans to gain high level technical jobs across the country. He became so engaged in the commercial aviation program he initiated that he learned to fly.”

Patterson readily respected and promoted the value of inter-relatedness between educational advancement and a nutritious diet. Instituted in courses taught at Tuskegee, his approach was nationally recognized by many, including President Lyndon B. Johnson. The president appointed Patterson, according to his biography on BLACKPast, to “oversee the development of the federally funded school-lunch program, which gave underprivileged children the opportunity to gain a strong nutritional base.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

The School of Veterinary Medicine opened at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in 1944. Patterson considered its creation, which was the first school of veterinary medicine at a Black institution of higher learning, as one of the most critical accomplishments of his life.

His support of aviation programming for African-Americans was also groundbreaking. With the outbreak of World War II, he lobbied for this cause to train young African-Americans to fly. Patterson ultimately won both a federal contract to establish a training site as well as government support for development of a full air base at Tuskegee. These achievements led to the development of the Tuskegee Airmen, who became icons in history.

It should be noted that “Tuskegee Airmen” actually references all, including bombardiers, control tower operators and dispatchers, instructors, maintenance workers, mechanics, medical personnel, meteorologists, navigators, parachute riggers, radio operators, supply personnel and technicians, who were involved in the “Tuskegee Experience” program.

These African-Americans fought extreme racial discrimination and became one of the most highly-respected military groups in American history. During the course of the war, 66 out of the 450 Tuskegee Airmen died in battle. The airmen engaged and defeated Messerschmitt Me 262s, the first operational jet fighters, and were awarded a total of eight-hundred and fifty medals!

Tuskegee Institute was selected by the U.S. Army Air Corps to train this new squadron for several reasons. The Institute had exceptional engineering and technical instructors, newly-constructed facilities that greatly supported aeronautical training and the essential climate that allowed for flying, regardless of the season. The students of the inaugural Civilian Pilot Training Program completed their program in May 1940. Because of its success, the Tuskegee program was greater developed and it became the training ground for African-American aviation during World War II.

The field was constructed in 1941 and named in tribute to Robert Russa Moton. Patterson’s father-in-law had passed the previous year.

Also actively involved in the Tuskegee community, Frederick D. Patterson devised a plan to better improve the quality of living, such as housing, for residents. Acknowledging the futility of homes made from wood, according to the biography on the United Negro College Fund website, “Realizing the capacity of his largely vocational college, he pooled available talent and resources and created an intricate program that trained and assisted the low-income citizens in building new, sound homes made of a unique concrete construction. Methods associated with the ‘Tuskegee concrete block’ were recognized by the federal government as a pragmatic approach to low-income housing and were adapted as models for rural homes, both domestically and internationally.”

Adding to these incredible aforementioned contributions, Patterson founded the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) in 1944, the same year that the veterinary school at Tuskegee opened. Seeking to make private, historically Black institutions of higher learning more financially stable, the Fund was the first cooperative fundraising venture in higher education in the United States. An essential resource for its member universities, it, according to the UNCF website, has the following statistics:

- 500, 000+ Students with college degrees, thanks to the UNCF

- $5 Billion+ Amount contributed to UNCF to date

- $11 Million Total awarded in scholarships to students in our top five cities: New York City, Atlanta, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C.

- 70% Graduating rate for UNCF scholarship recipients is nine percentage points higher than the national average for all students at four-year colleges

- 400 UNCF programs award 10, 000+ scholarships every year

Patterson concurrently served as both the president and chief executive office of the United Negro College Fund from 1964 to 1966.

(No copyright infringement intended).

His work in advancing opportunities for those engaged in higher education include serving on the President’s Commission on Higher Education (he was invited by President Harry S. Truman); acting as the director of the Phelps-Stokes Fund; and founding the Robert R. Moton Memorial Institute. His work on the commission was critical, as it led to a more diverse university education beyond the Eurocentric agenda, the creation of a community colleges collective and development of Title III of the Higher Education Act of 1965. The latter program was designed to federally aid Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), institutions of higher education that serve large concentrations of minority students who, historically, have been underrepresented in higher education.

Frederick D. Patterson led the Phelps Stokes Fund as director from 1953 to 1958 and as president, from 1958 to 1969. This foundation sponsored educational programs for youths, significantly African-Americans, Africans, and Indigenous Americans, with promise despite disadvantages in life. The non-profit he founded in tribute to his late father-in-law improved the administrative, including management and recruitment, processes of historically Black colleges and universities.

(No copyright infringement intended).

By the 1970s, he started the College Endowment Funding Plan. This program supported academic institutions with matching contributions from private businesses and the federal government.

Frederick D. Patterson remained active in education throughout the rest of his life. On April 26, 1988, he passed away at his home in New Rochelle, New York; he was eighty-six years old. His ashes are buried on the grounds of Tuskegee University.

A member of Sigma Pi Phi and Alpha Phi Alpha fraternities, Frederick D. Patterson was a champion of education. To him, education was essential to upward mobility and enhancing life. He served on the boards for several historically Black colleges and universities such as Hampton University, Bennett College and of course, Tuskegee University. For his lifetime work, he has received numerous accolades. These include a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1986 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the most prestigious award a civilian may be awarded by the president of the United States, in 1987. He also was the recipient of twenty honorary degrees from nineteen institutions of higher learning.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Because of his immense influence in higher education, significantly for African-Americans, the Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute was established by the United Negro College Fund in 1986. It is located within the UNCF headquarters in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C. and is near Howard University, a historically Black university. This institute is considered to be, according to the UNCF website, “the nation’s foremost research institution regarding educational issues facing African Americans from preschool to adulthood … it was established to design, conduct, and disseminate research to guide policy makers toward improving the educational opportunities for African Americans and other people of color.”

Frederick D. Patterson truly embodied the sentiment of the inscription on his Presidential Medal of Freedom. Engraved is, “By his inspiring example of personal excellence and unselfish dedication, he has taught the nation that, in this land of freedom, no mind should go to waste …”

“The more conservative element of Negroes differ from those who hold the most radical views in opposition to segregation only in terms of time and technique of its elimination. All Negroes must condemn any form of segregation based on race, creed or color.”

~ Frederick D. Patterson