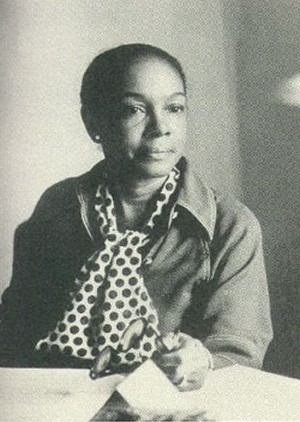

“Her career focused attention on the particular problems faced by minority youth, and her work ushered in new approaches to treatment and remains a landmark in the history of psychology.”

~ Encyclopedia of Arkansas

In Hot Springs, Arkansas, Harold H. and Kate Florence Phipps welcomed their daughter, Mamie, into the world on October 18, 1917. Harold, who emigrated to the United States from the British West Indies, worked as a physician and Kate aided him in managing his practice. The importance of family, self-sufficiency and education was paramount in the Phipps family, which included her brother, Harold.

Bright and accomplished, she excelled in learning, including at Langston High School from where she graduated in 1934. Mamie attended segregated schools but she enjoyed privileges, such as being involved in recreational activities and going away on holiday, that many other Blacks were unable to enjoy. She was mindful that her parents’ education, industry, perseverance and commitment were the source of her happiness. Mamie knew that not many Black men managed places of the elite, such as her father did at a private resort, and that not many Black women had the opportunity to be a housewife and not work, such as her mother. Her respect for her parents’ sacrifices was greater enhanced by this understanding and further propelled her in her personal drive to be excel.

Upon graduation, 16-year old Mamie Phipps elected to attend Howard University, a historically Black institution of higher learning in Washington, D.C. Although she had offers elsewhere, she selected Howard University because of its stellar reputation and exceptional faculty. Choosing to study mathematics and physics, she soon discovered that her interests were not supported. Phipps believed this was due to sexism against women entering a field dominated by men.

She shared her frustrations with Kenneth B. Clark, her professor and a graduate student, who encouraged her to change her major to psychology. His suggestion was rooted in support of Mamie’s interests in children’s learning. In 1937, Clark, prompted by his mentor Francis Cecil Sumner, entered the doctoral program at Columbia University in the City of New York. This was sound advice, as Sumner, the “Father of Black Psychology”, was the first African-American to earn a doctorate in psychology (Lincoln University in 1920).

While Clark studied in his former home city, he and Mamie remained in touch and their friendship blossomed into romance. Despite the objections of her parents who felt her formal education would be compromised for several reasons, Kenneth and Mamie eloped in 1937. In 1938, Mamie Phipps Clark graduated magna cum laude from Howard University.

Following, Mamie earned a fellowship to enter Howard University’s graduate program in psychology. During this time of pursuing her master’s degree, two experiences significantly impacted her life.

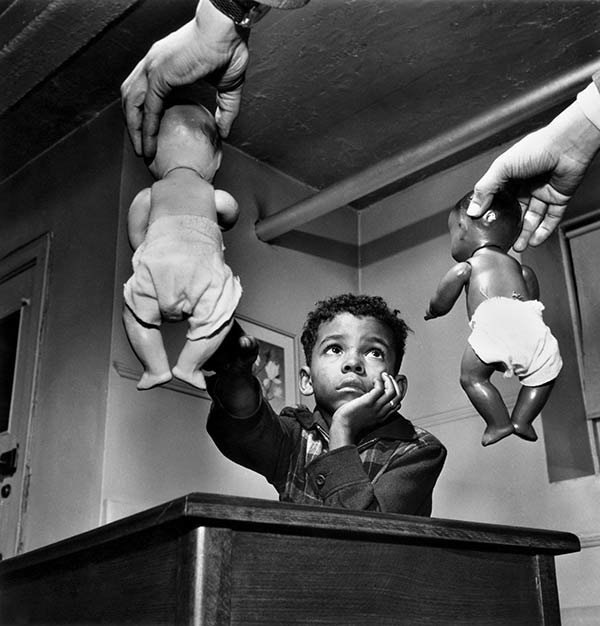

The first experience was her working in the law offices of Charles Hamilton Houston, who famously fought racial discrimination. Known as “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow”, Houston led the Law School at Howard University and trained many attorneys, including future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, in the area of civil rights. At this time under Hamilton, she also worked in a nursery for African-American children. Developing on the self-identity work of Gene and Ruth Horowitz, Mamie Phipps Clark undertook research to apply to Black children’s sense of identity and esteem. This research would be the focus of her Master of Arts thesis, “The Development of Consciousness of Self in Negro Pre-School Children” at Howard University. In her work, the second experience, she assessed the nursery children’s development of racial identity, incorporating items such as a coloring test and notably, “White” and “Black” dolls.

Mamie Phipps Clark’s findings concerning the dolls, according to her biography stub at the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, “entailed an experiment which demonstrated that young Black children, when presented with identical dolls — one Black and one White — preferred the White doll over the Black doll. The major findings were that Black children “became aware of their racial identity at about age three, and — simultaneously with their awareness of racial identity — acquired a negative self-image.” In Women in Psychology: A Bio-Bibliographic Sourcebook, her groundbreaking study “into the importance of self in Black children, completed fifteen years before the Brown decision, paved the way for an increase in psychological research into the areas of self-esteem and self-concept.”

Supporting each’s research, Kenneth and Mamie soon collaborated professionally, including publishing their findings on race recognition and self-worth in academic journals and presenting at conferences. In 1939, a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for Mamie was awarded, providing an additional three years of support for their research and her studies at Columbia University in the City of New York, where she too had entered to pursue her doctorate in psychology. She was the only Black student in the department.

In 1940, Kenneth B. Clark graduated with his Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology, becoming the first African-American to earn a doctorate in psychology from Columbia University. Three years later, Mamie Phipps Clark earned her Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology, making her the first woman and second African-American to earn a doctorate in psychology from Columbia University. The title of her dissertation was “Changes in Primary Mental Abilities with Age.” During this time, the Clark couple were blessed with two children: Kate Miriam, born in 1940, and Hilton Bancroft, born in 1943.

(No copyright infringement intended).

After graduating from Columbia, Mamie Phipps Clark felt extremely frustrated at the lack of opportunities for Black women psychologists. From 1944 to 1946, she worked for the American Public Health Association, analyzing data about nurses, and at the Unites States Armed Forces Institute, undergoing psychological research. All too often, she found herself being employed in positions for which she was overqualified and underutilized, considering her expertise and experience.

In 1946, the Clarks founded the Northside Child Development Center in Harlem. An inspiration for the development of this center was based upon her previous work, performing psychological testing on homeless Black girls at the Riverdale Home for Children. Mamie found this work highly rewarding but was severely troubled by the dearth of psychological services for Black and Brown children.

With donations from Mamie’s parents and volunteerism from their colleagues in psychology and social work, the Center, according to Encyclopedia.com, was “the first full-time child guidance center in Harlem to offer psychiatric, psychological and casework services to children and families.” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas detailed, “The center was the first full-time institution in the Harlem area that offered psychological and casework services to local families. The work carried out there helped to establish that the problems of minority children are psycho-social in nature and that ‘orthodox psychoanalytically-oriented psychiatric treatment is not necessarily the most effective way of helping families whose massive problems are associated with living in a ghetto.’”

A critical instrument of their work and outreach was intelligence testing. The Clarks used this to refute public schools’ ideology and disavow their intentional placement of minority children in programs for those with developmental delays. Mamie acted as the Director of the Northside Child Development Center until she retired in 1979.

By the 1950s, the Clark research was used in battling segregation inside the courts of America. In an ironic instance, Mamie Phipps Clark used her and her husband’s research to rebut the testimony of Dr. Henry Garrett in a de-segregation case. He was vehemently against the integration of public schools. Garrett, who was racist, had been her dissertation advisor when she studied at Columbia University.

The Clarks’ paper, “The Effects of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development” presented at the Mid-Century White House Conference on Children and Youth was highly influential in building with individuals and organizations. The organization with whom the Clark couple became most famous for collaborating with against segregation was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Having studied more than two-hundred Black children, the Clarks’ work detailed their findings of race’s influence on self-identity and esteem in “The Effects of Segregation and the Consequences of De-Segregation: a Social Science Statement”.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The psychologist couple concluded that segregation was psychologically destructive. This result was integral in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that outlawed segregation in public education. Thurgood Marshall, an attorney of the NAACP who argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, used the Clarks research to illustrate the devastation Black children suffered due to legal segregation that all too often was not “separate but equal”, as per the judgement of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In giving their decision on Brown v. Board of Education, the federal court emphasized the importance of the Clarks’ work. The Court affirmed that segregation, according to Encyclopedia.com, “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect the children’s hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” This groundbreaking decision greatly impacted Blacks and their opportunities for personal, familial and community advancement.

Even though progress was being made with the ending of segregation in public schools, the Clark couple knew that measures of economic and political empowerment had to be undertaken in order to address and heal the ills Blacks experienced brought about by poverty. Accordingly, in 1962, Kenneth B. Clark co-founded Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU). The purpose of this organization was to develop educational and employment opportunities for those in need. In order to devise programs, the Clark couple undertook extensive research of factors impacting Harlemites. These factors included education levels, housing, income and incarceration. Experts in various career fields were sought to re-structure community institutions in Harlem. The HARYOU program inspired the War on Poverty program initiated by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Mamie Phipps Clark was active outside the fields of social and psychological research, sitting on the boards of trustees for institutions and advisory boards of non-profit agencies whose missions she held dear. These included Teachers’ College, Columbia University in the City of New York; the American Broadcasting Company (ABC); the New York Public Library; the Museum of Modern Art; and the New York Mission Society.

On August 11, 1983, Mamie Phipps Clark passed away at their home in New York. Losing her battle against cancer, she was sixty-six years old.

Her rich legacy, like her husband’s, is immeasurable. History has not treated her as prominently as her husband, primarily due to its societal regard for and practices of patriarchy. However, the research and findings of Mamie Phipps Clark was critical in expanding the strict paradigms of developmental psychology. Prior to her research, this field excluded diverse interpretations of issues, primarily societally-induced, that Blacks experienced and the appropriate treatments therein.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The recipient of numerous awards and accolades, the Clarks’ research prompted the 1951 creation of Saralee, the first-mass produced African-American baby doll. In 1983, Mamie Phipps Clark was the recipient of the Candace Award for “Humanitarianism” by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women. She also was gifted an honorary degree from Earlham College. This institution’s degree to both Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark was awarded in 2004 in honor of the 50th anniversary of their legendary work in Black psychology and civil rights. In 2017, the Department of Psychology at Columbia University in the City of New York, the Clarks’ alma mater, created the Mamie Phipps Clark and Kenneth B. Clark Distinguished Lecture Award in recognition of a senior scholar’s outstanding contributions to race and justice.

The Northside Childhood Development Center, which first opened in a basement apartment in the Dunbar Houses on 158th Street, ultimately moved to Arthur A. Schomburg Plaza on 5th Street. In Children, Race, and Power: Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s Northside Center by David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, Dora Johnson raved about Mamie Phipps Clark. A member of the center’s staff, she exclaimed that the esteemed psychologist and director “… embodied the center. In a very real way, it was her views, philosophy, and her soul that held the center together … when an unusual and unique person pursues a dream and realizes that dream and directs that dream, people are drawn not only to the idea of the dream, but to the uniqueness of the person themselves.” The center continues to successfully meet the contemporary challenges of Harlemites in need.

“The discrepancy between identifying one’s own color and indicating one;s color preference is too great to be ignored. The negation of the color, brown, exists in the same complexity of attitudes in which there also exists knowledge of the fact that the child himself must be identified with that which he rejects.”

~ Mamie Phipps Clark