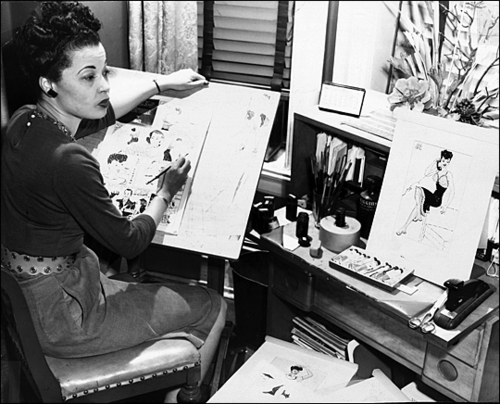

“Ormes’ comic strips were syndicated in Black newspapers in the 1930s and ‘40s, making her the only nationally syndicated, Black woman cartoonist until the 1990s … Her characters were fashionable and intelligent, setting a new precedent for Black depictions of that day (1937-56).”

~ Kate Kelly, founder, America Comes Alive! blog

Named Zelda Maven, a baby girl was born to William and Mary (née Brown) Jackson on August 1, 1911 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. When she was only six years old, her father died in an automobile accident. As a result, Zelda and her older sister, Dolores, briefly lived with their aunt and uncle. With the re-marriage of Mary, the family moved to Monongahela, a quiet suburb outside Pittsburgh.

Her passion for illustrating began when she was a young girl. At an early age, Zelda loved to draw and write, perhaps moreso, because it strengthened a connection with her late father. The owner of a printing company and movie theater, William had also been an artist and writer.

When Zelda Jackson was a student at Monongahela High School, she became the arts editor of the school’s yearbook committee. She was chosen, according to Bio.com, to manage art duties for her high school yearbook during her junior and senior years, where she displayed what would be her future trademark, “her on-the-page wit”. Featured in the 1929-30 yearbook are caricatures of students and faculty that Zelda created. It was also during her youth that she began to be called “Jackie,” a nickname of her surname.

Upon her graduation from Monongahela High School in 1930, she married Earl Clark Ormes in 1931. Initially, the Ormes lived in Ohio so that he could be near his family. They had a daughter, Jacqueline, who, sadly, passed away at three years old due to a tumor in her brain.

Jackie began a professional relationship with the Pittsburgh Courier, an African-American owned newspaper whose target audience was the Black community. The affiliation began when Jackie wrote of her interests to the Courier’s editor, Robert Vann. She must have impressed those at the Pennsylvania newspaper because Ormes first comic strip, Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem, premiered in the Pittsburgh Courier on May 1, 1937. The strip ran until April 30, 1938.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Read across the country, Ormes’ strip featured “Torchy Brown”, an attractive, African-American young woman who left Mississippi to live in the Harlem community in New York City. Her dream was to perform at The Cotton Club. Combining action and adventure with hijinx and humor, the strip illustrated the trials and triumphs of African-Americans, especially those who undertook The Great Migration. The publication of Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem made her the first African-American woman to work as a professional newspaper cartoonist.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Vann also provided her with her first writing assignment. This opportunity, as a sports writer, was to cover the 1939 heavyweight boxing match between Joe Louis and John Henry Lewis. Her involvement in reporting on the boxing matches prompted her to become an avid and lifelong fan of the sport. At the Pittsburgh Courier, Jackie also worked as a proofreader, editor and freelance writer whose topics ranged from human interest to crime. Though these positions provided interesting work, Ormes’ true career passion was to be an artist.

In 1942, the Ormes moved to Chicago, where they became an active part of the affluent African-American community. Jackie performed freelance work, composing articles and, for a short period, penning a column for the society page in the Chicago Defender, one of the most prominent, Black-owned newspapers in the United States. Earl worked as an accountant and also as a manager of the Sutherland Hotel, a highly-regarded hotel for African-Americans.

The Ormes were happily married for forty-five years until his passing in 1976. His position was pivotal in being able to provide a service when Blacks were barred, due to segregation, from many public accommodations. Her work was powerful in detailing the lives of Blacks beyond the negative stereotypes that were proliferated via the media. According to Kate Kelly in “Jackie Ormes (1911-1986), First African-American Female Cartoonist” on the America Comes Alive! blog, their life together allowed the Ormes to become a “… part of Chicago’s Black elite, and they socialized with the leading political figures and entertainers of the day.”

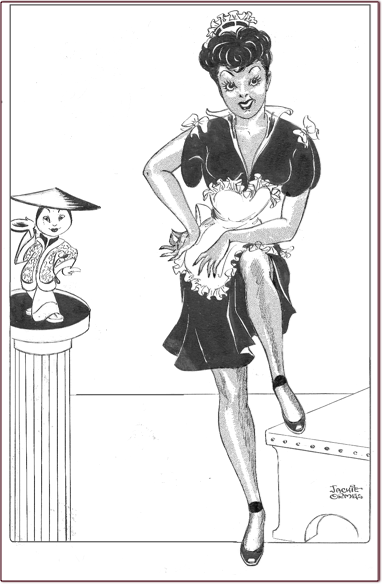

Ormes continued drawing and on March 24, 1945, the Chicago Defender ran her new comic strip, Candy. A single-panel illustration, the character, “Candy”, was a pretty and clever woman who was employed as a maid. This strip, which was a highlight on the editorial page, ran in the Illinois publication until July 21, 1945.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On September 1, 1945, Ormes’ third comic strip, Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, was featured in the Pittsburgh Courier, the Black newspaper who provided her with her first opportunity in journalism and cartooning. This single-panel comic centered upon the wise, if not precocious, insight of six-year old Patty-Jo and her interactions with Ginger, her older sister, and society. Ginger, always stylishly dressed, is referenced by author Tim Jackson in his Pioneering Cartoonists of Color as only speaking once in the eleven years that the comic ran. Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger remained in production until September 22, 1956.

(No copyright infringement intended).

With this third comic, Jackie Ormes presented scenes from African-American life in which its Black characters were bright and cultured. Ormes was groundbreaking in this presentation, as Jackson praised, “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger showcased the lifestyles of educated, middle-class African Americans at a time when popular mainstream comic strips clung tenaciously to negative, insulting images of Black people. Particularly, the images of Black women generally consisted of crudely drawn, obese, domineering, husband-beating, Blackface mammies. If not this, she was the dowdy, unappealing maid, or on the opposite end of the spectrum, the hypersexual, amoral party girl. In the latter case, she might be still further degraded by being portrayed as a gratuitously crude and essentially naked Blackface stereotype, as with Robert Crumb’s ‘Angelfood McSpade’.”

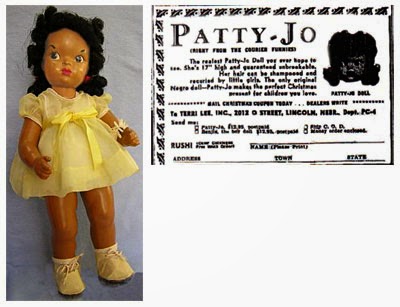

In 1947, Jackie Ormes introduced the Patty-Jo Doll. This doll was manufactured by Terri Lee, a doll company founded the previous year in Lincoln, Nebraska by Violet Lee Gradwohl. The Patty-Jo Doll was preceded by the Bonnie Lou Doll, another Black doll. Both were 16” tall, comprised of Celanese plastic and wore hair that was sourced from high quality wigs.

However, there were two distinct differences between the Patty-Jo Doll and the Bonnie Lou Doll: the Patty-Jo Doll was not a baby doll and it was the first African-American doll that was based upon a comic strip character. Additionally, the features on the original Patty-Jo Doll were painted on by Ormes. Many believed the Patty-Jo Doll character was based upon her late daughter, Jacqueline, so the appearance of the doll was that of a little girl.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In Jackie Ormes: The First African-American Woman Cartoonist, a biography written by Nancy Goldstein, the author wrote, “In mid-20th century America, most Black folks represented stereotypes, like mammies, dolls advertised as ‘picaninnies’, and raggedy little boys and girls. Jackie Ormes said, ‘No […] more … Sambos … Just KIDS!’ and she transformed her attractive, spunky Patty-Jo cartoon character into the first, upscale, American Black doll. At long last, here was an African-American doll with all the play features children desired: playable hair, and the finest and most extensive wardrobe on the market, with all manner of dresses, formals, shoes, hats, nightgowns, robes, skating and cowgirl costumes, and spring and winter coat sets, to name a few.”

The Patty-Jo Doll was released in time for the Christmas holiday and was a huge success with children, Black and White. Because of the popularity, Ormes soon included a new character, Benjie, in her Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger comic strip. Benjie originally was the male companion doll to Bonnie Lou. He, too, was 16” tall, made of Celanese plastic and had his own wardrobe. Because the Patty-Jo Doll only remained in production until 1949, it is a collector item.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

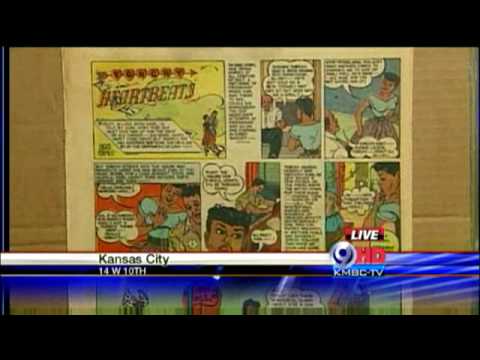

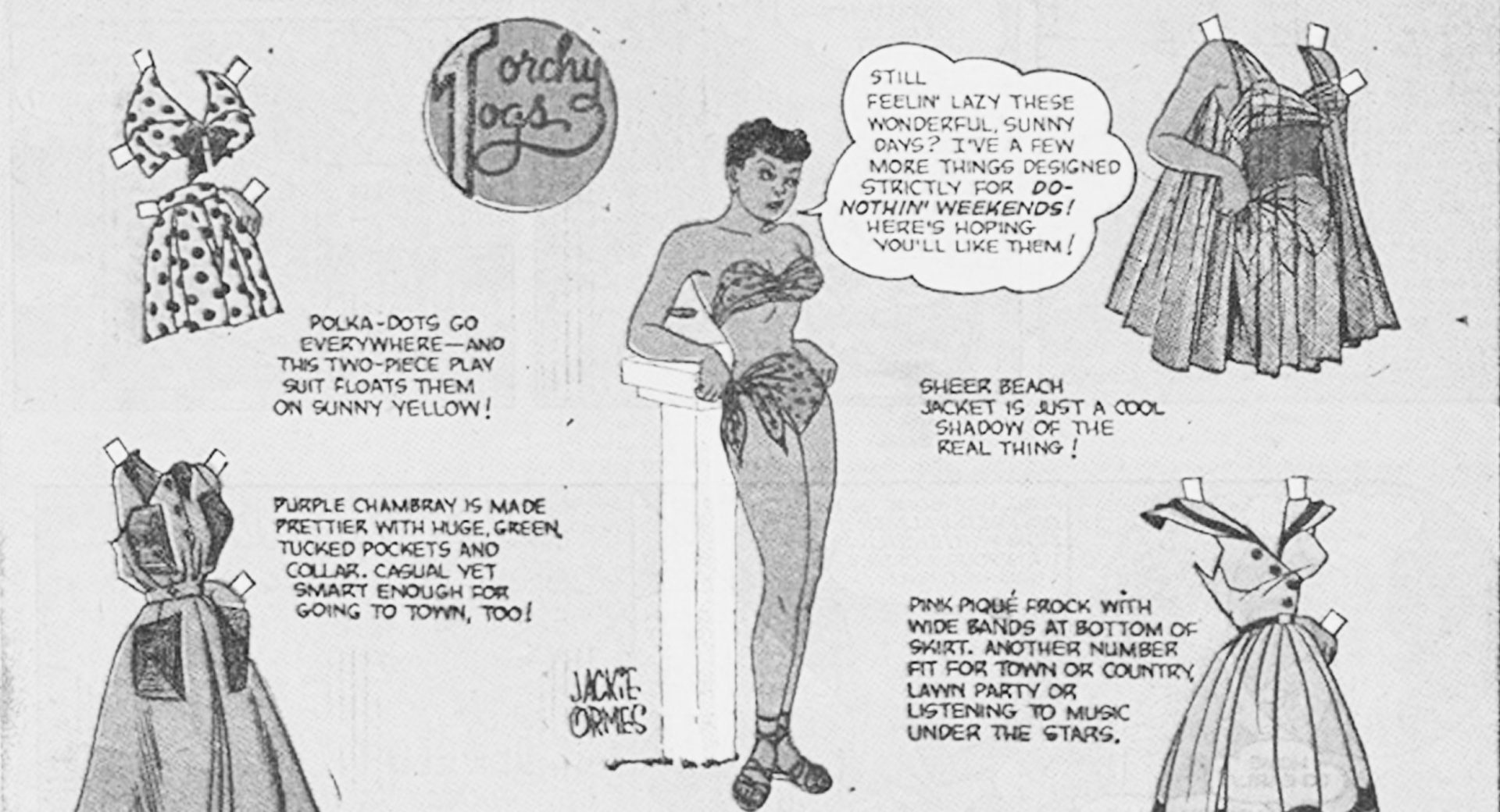

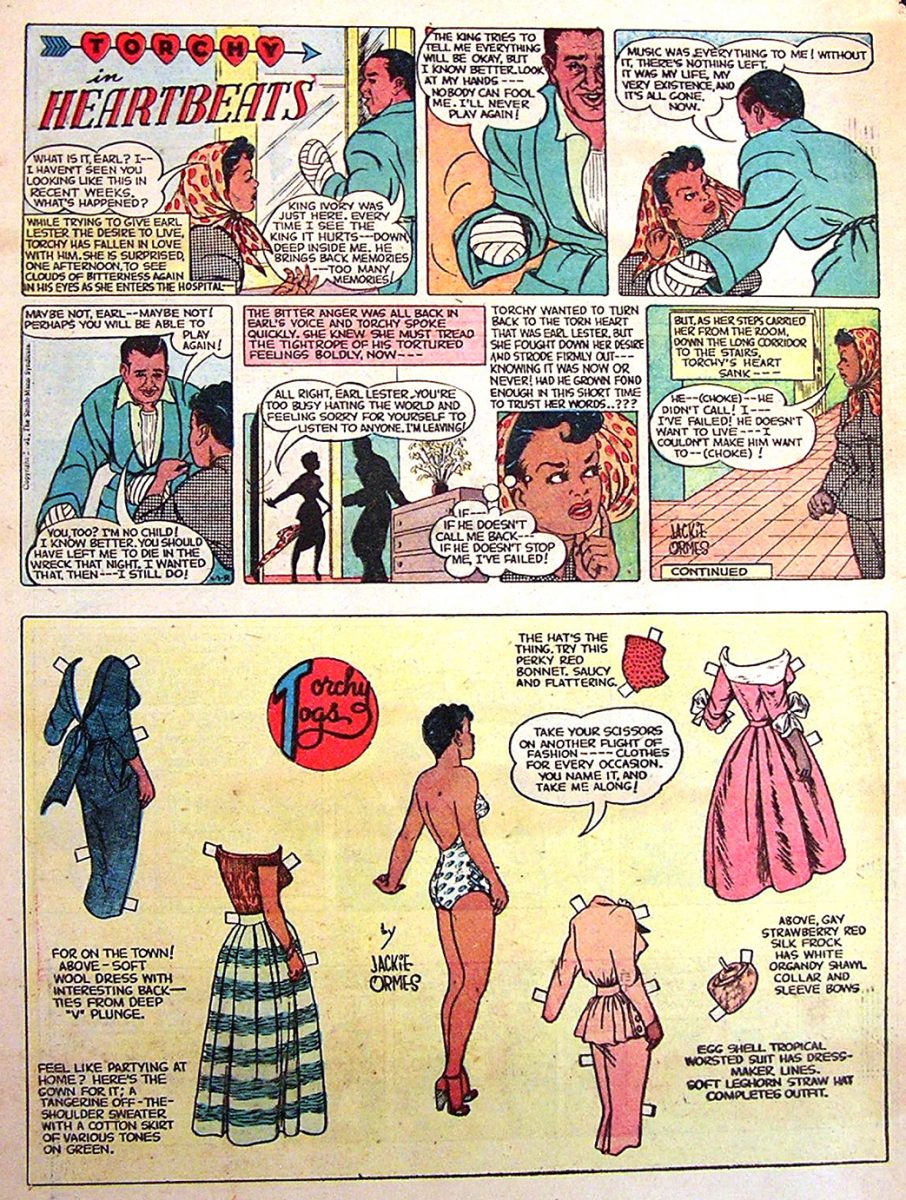

The following year, Jackie Ormes revamped her character, “Torchy Brown” and on August 19, 1950, the Pittsburgh Courier featured her new comic strip, Torchy in Heartbeats. Inked in color, this strip showcased the adventures of Torchy. Unique to this strip was that it contained a “topper”, which was an additional single panel that served as a secondary strip. Titled Torchy Togs, Ormes included a “paper doll” of Torchy and stylish fashions to “dress” her.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Uchenna Edeh elaborated on the return of this beautiful and independent character in “Jackie Ormes: The First Professional African American Cartoonist” for Kentake Page blog. In the article, Edeh cheered, “Torchy was as brave and confident as ever. Although the strip was ostensibly about Torchy’s search for romance, she still provided a vehicle through which Jackie could express her political views. Ormes used her character as a great looking role model who also took on issues like sexism, racism, and the polluting of the environment.” The final installment, published on September 18, 1954, is probably for what Torchy in Heartbeats is best remembered.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In this story arc, Torchy, who recently completed her training as a nurse, and her boyfriend, Dr. Paul Hammond, have relocated to Southville. In this impoverished, rural, primarily African-American populated community, he has set up his new medical practice. However, the couple soon discovers the dangers that the Southville residents have been facing.

In Ecomedia: Key Issues, edited by Stephen Rust, Salma Monani and Sean Cubitt, the editors present how pioneering Ormes and Torchy Brown in Heartbeats was, from an ecocritical perspective. In the text, it was reported that, “Torchy applies her talents to fighting the environmental racism of Colonel Fuller, owner of the ‘huge Fuller Chemical Plant’, which ‘is slowly poisoning the entire community’ of the predominately Black town of Southville (4 July 1953). Ormes used the form of serial publication to activate a retroactive riskscape, signaling the ethical imperative of responding to the comprehensive environmental community.”

In 1956, Jackie Ormes retired from cartooning. Although she suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, she remained active in creating art, including portraits and murals, until her condition would not allow it. Ormes, an active member of doll clubs, was an avid collector of antique and contemporary figures.

Her activism in the Chicago arts community continued, despite her having been targeted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation during the late 1940s. Although some believed it was because of her liberal stance in politics, a more recent version of this investigation relays that it was enacted due to her being in a bookstore that had been frequented by supposed Communists. Ormes also produced fashion shows and presented entertainment showcases in support of her South Side community. Additionally, she was a founding member on the Board of Directors of the DuSable Museum of African American History, which houses her papers.

On December 26, 1985, Jackie Ormes passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage; she was 74 years old.

A trailblazer, entrepreneur, socialite and activist, Jackie Ormes laid the foundation for a new, dignified and diverse way for African-Americans, especially females, to be represented. Author Nancy Goldstein in her Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist detailed Ormes pioneering work. The author championed, “People who knew her say that she modeled some cartoon characters after herself as beautifully dressed and coiffed females, appearing and speaking out in ways that defied stereotyped images of Blacks in the mainstream press … Her topics include fashion, modern life, and human foibles, as well as racial injustice, foreign and domestic policy, educational equality, the atom bomb and environmental pollution, among other pressing issues of those times, and indeed, of ours today.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 2014, Ormes was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame. In 2018, she, as a Judges’ Choice, was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Industry Eisner Award Hall of Fame.

“I have never liked dreamy, little women who can’t hold their own …”

~ Jackie Ormes