“He broke the color barrier twice, as the first African American comic strip cartoonist whose work was widely syndicated in mainstream newspapers and as the creator of the first syndicated strip with a racially and ethnically mixed cast of characters.”

~ Paul Vitello, journalist, The New York Times

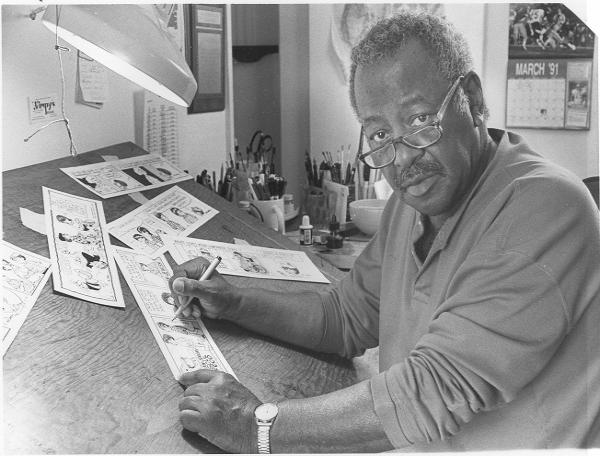

Morris Nolten Turner was born on December 11, 1923 in Oakland, California; he was the youngest of four children. His parents, James and Nora Spears Turner, were devout Christians. Highly active in rearing their children, a principle that Morris would hold dear throughout his long life was “Keeping the Faith”. His mother was a homemaker and worked as a nurse; his father worked as a Pullman porter who often was away.

From an early age, Morrie, as he was called, was connected with newspapers. His father, as a Pullman porter, was a member of a group of Black men who, for years, operated as a covert delivery network of Black newspaper. These papers included the Chicago Defender, the New York Amsterdam News, and the Pittsburgh Courier. Additionally, his brothers also sold Black newspapers.

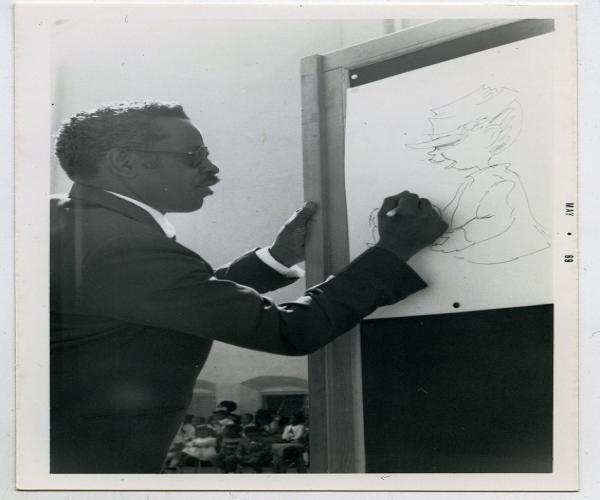

A talented young child, Morrie began sketching caricatures when he was in the fifth grade at Cole Elementary. According to journalist Paul Vitello in his 2010 memorial tribute to Turner in The New York Times, it was his mother who was incredibly encouraging of “… his artistic talent and instilling in him a reverence for a pantheon of Black historical figures.”

His art, including creating cartoons, made him highly popular with others. Turner enjoyed cartoons, such as Bootsie, featured in newspapers. He especially admired the work of Oliver “Ollie” Harrington, an African-American who was featured in the New York Amsterdam News. Turner was incredibly impressed by Harrington and by the time he was a teen, he began collecting his work and copying Harington’s style.

In “Morrie Turner: To Say the Name is Both Eulogy and Tribute”, written by R.C. Harvey for The Comic Journal, the journalist reported an account of when Turner wrote Milton Caniff. Caniff, a White, grandmaster cartoonist who is best known for Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates, sent to Turner a typed, six-page response. In his letter, Caniff included tips and concepts regarding illustration and storytelling. Harvey shared the impact of Caniff on Turner, relaying, “It changed my whole life … The fact that he took the time to share all with a kid, a stranger. Didn’t impress me all that much at the time, but it impresses the hell out of me now.” The generosity of Caniff surely influenced the magnanimity of Morrie Turner, who often shared his wisdom and expertise with aspiring cartoonists, especially African-American artists.

When he entered McClymonds High School, his personality and art assisted in his being elected to serve on student council and work on the school newspaper. However, the racism of others stunted his opportunities and accomplishments. According to Mary Kentra Ericsson in the biography, Morrie Turner: Creator of Wee Pals, Turner was often denied the rights and privileges afforded a student council member. One instance of this racial discrimination occurred when he was forbidden to speak on the agenda at a school assembly and even replaced by a White girl who had been his runner-up. He also was omitted for receiving bylines and masthead credit.

By the time Morrie Turner was fourteen years old, he was determined to be a professional cartoonist. His parents disagreed on his career selection and James often took down Morrie’s art that Nora displayed. Adding to the tension, he also became disenchanted with his school environment and began to hang out with a “rough crowd”. His parents thwarted this unwanted development when the Turner family moved from Oakland to Berkeley, where he graduated from Berkeley High School in 1942.

In 1943, during World War II, Turner joined the U.S. Army Air Corps. He would be stationed at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was here that the all-Black 332nd Fighter Group, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen, and the all-Black 477th Bombardment Group were trained. As a member of the 477th, Turner, according to several sources, worked in various capacities as a guard, mechanic and staff clerk. He, as a reporter and illustrator, also contributed to the base’s newspaper.

His work gained notice and he created a comic strip, Rail Head, for the military newspaper, Stars and Stripes. Turner’s series was about the misadventures of a young cadet and was sourced from the cartoonist’ own experiences in the armed services.

Upon being honorably discharged from the U.S. Army, Morrie Turner returned home to California. On April 6, 1946, he married his childhood sweetheart, Letha Harvey. They were blessed with one child, a son who became known as Morrie, Jr. Turner continued to pursue his passion of illustration while working in different employment positions, including as a radio program host and comedian. In 1954, he was hired to be a clerk with the Oakland Police Department, where he worked for ten years.

In his spare time, he created art for charities and founded his own greeting card company. However, he worked to develop his career as a cartoonist and earned $5.00 for the first sale of one of his cartoons; it was bought by Baker’s Helper, a baking industry publication. His big break was when he was paid $75 from Better Homes and Garden for another one of his cartoons.

His free-lancing of illustrations and cartoons led to the national publication of his work in industrial, trade and domestic journals and magazines, including the Saturday Evening Post. His work was prominently featured in Black publications such as the Chicago Defender, Ebony and the Negro Digest. The Defender was founded by African-American publishing pioneer Robert S. Abbott. The latter two were creations of African-American publishing great, John H. Johnson.

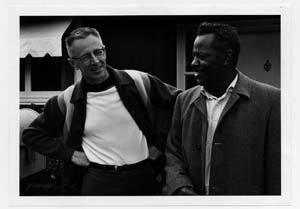

In 1963, Morrie Turner became a member of the Association of California Cartoonists and Gag Artists; he was the only Black member. Shortly thereafter, Morrie Turner became friends with White cartoonists Charles Schulz and Bil Keane, creators, respectively, of Peanuts and Family Circus.

(No copyright infringement intended).

During the early 1960s, much was culminating regarding race-relations in the United States. Turner wanted to be active in the Civil Rights Movement but his physical location, work and family status hindered him from being actively involved in ways that he desired. However, conversations with activists, notably Dick Gregory, and encouragement to develop work that was more representative of his Black life experiences motivated him to begin his own strip. In a discussion with Schulz, Turner questioned why there were no Black characters in Peanuts. Schulz encouraged Turner in Turner’s decision to create his own strip that starred Black characters.

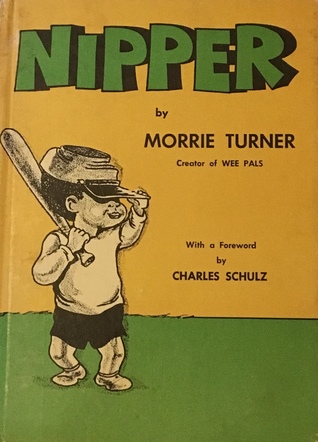

Turner began creating Dinky Fellas, whose featured cast were all-Black. He likened the strip to a Black version of Peanuts. In the Harvey article, Turner envisioned the possibility of his forthcoming character as a Black “Charlie Brown”. Turner, according to Harvey, also speculated the possibility of his starring character wearing a Civil War cap, “… And what if the cap were a Confederate cap? Now that, wrote Tom Carter in the Cartoon Club Newsletter, was ‘indeed a laugh – a child so naïve he could sweep away generations of ill will with one innocent, ironic gesture.’ That set everything in motion, Morrie said.”

features a foreward by Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts

(No copyright infringement intended).

The main character of Dinky Fellas was a wise and soulful, African-American boy, Nipper. He was named after African-American comedian Nipsey Russell, but Morrie was the true inspiration behind this character. Premiering on July 25, 1964, only the newspaper of his home city, the Berkeley Post, and the national Chicago Defender carried Turner’s strip; both of these publications were Black-owned. Due to the efforts and promotion of Lew Little, a salesman with a newspaper syndicate, Dinky Fellas was carried in three nationally-syndicated newspapers, including the Los Angeles Times, by February 1965.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Turner also was a member of the National Cartoonist Society. The society selected Turner as one of only six cartoonists, which included Keane, to cover the Vietnam War. He spent almost a month situated on the front lines and also visited hospitals. During his time in Vietnam, he drew more than 3,000 caricatures of Americans in military service.

By the mid-1960s, the United States, in facing powerful demands for greater political, social, and economic equality, was undergoing numerous challenges. The Civil Rights, Free Speech, Anti-War and Black Power movements were in full effect. Inspired by these movements and envisioning a more equitable society, Turner expanded Dinky Fellas, which at that point was carried in five nationally-syndicated newspapers.

Turner ultimately expanded the content and characters of his strip and its name, Dinky Fellas, was retired in December of 1965. Renamed Wee Pals, the strip transcended race, ethnicity, religion and gender (also later, ability). That year, Wee Pals became the first American syndicated comic strip that was culturally diverse. While many still considered it to be subversive, Turner saw his work as honoring differences and celebrating their uniqueness.

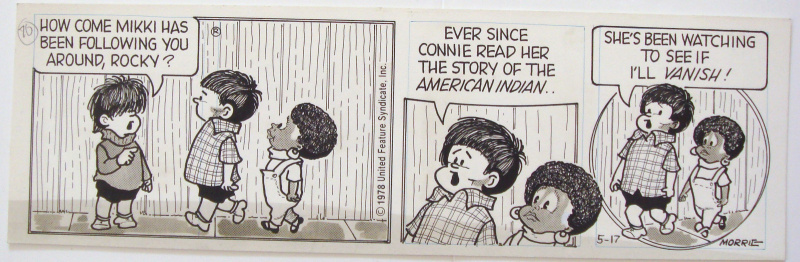

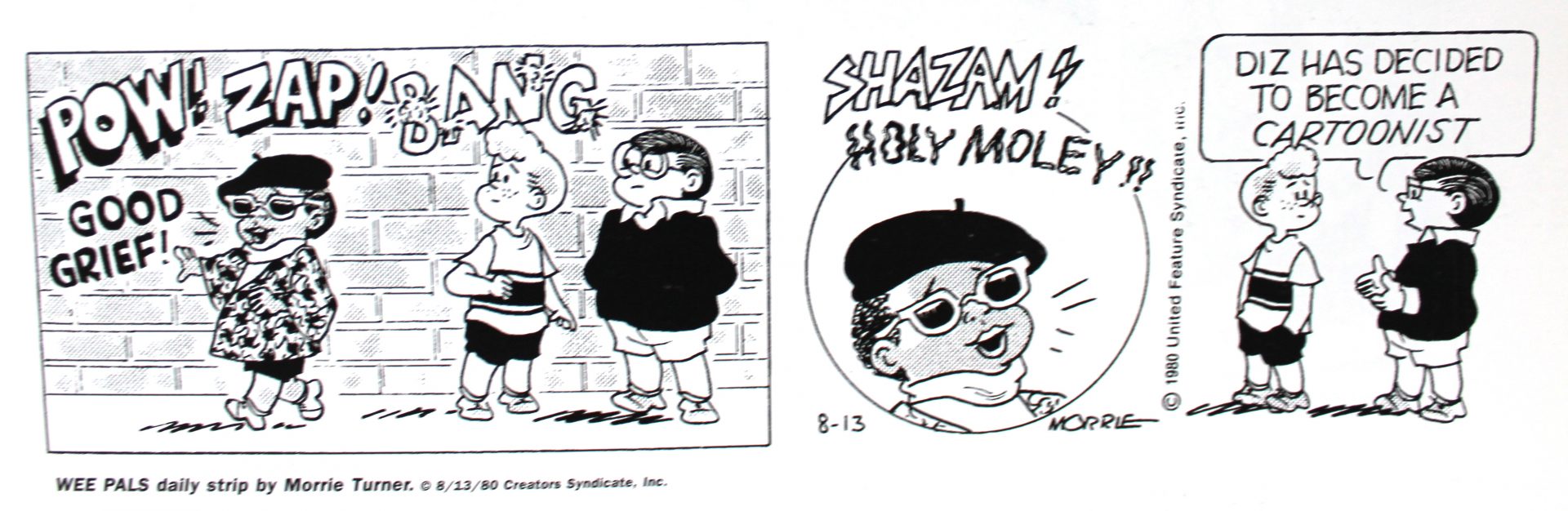

Promoting “Rainbow Power” of all five of the races, Black, Brown, Red, Yellow and White, Morrie Turner called for collective unity. In the article featured in The Comic Journal, Harvey detailed the characters, writing, “The diminutive buddies started with Nipper, whose Confederate Army cap always masks the top half of his face, and Nipper’s dog named General Lee; a soul brother named Randy; the chubby white bespectacled intellectual Oliver; Peter, a Mexican American; Rocky, a Native American; a Latino named Pablo; Diz, a beret-wearing, hip African-American proudly wearing a dashiki and sunglasses; George, an Asian American; Connie, a spirited feminist; the freckle-faced Jewish Jerry; and Sibyl Wrights, a black girl who was modeled on Morrie’s wife and Shirley Chisholm, the late New York congresswoman and civil rights leader.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

On April 4, 1968, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. A tragic by-product of this murder led to the increase of interest in Wee Pals. In “Pioneering Cartoonist Morrie Turner Dies”, a tribute article Cory Golden wrote for Davis Enterprise, Turner lamented, “Then a terrible thing happened – Martin Luther King was killed … in 30 days, 30 more papers began running my strip. In 30 more days, it was up to 60. You can imagine how I felt. I felt like I was benefitting from the death of one of my heroes.”

The mass support of Turner and his vision of a more egalitarian and harmonious society led to Wee Pals being featured in more than 100 newspapers throughout the world. The “Rainbow Power” strip was carried by these global newspapers less than three months after the killing of King.

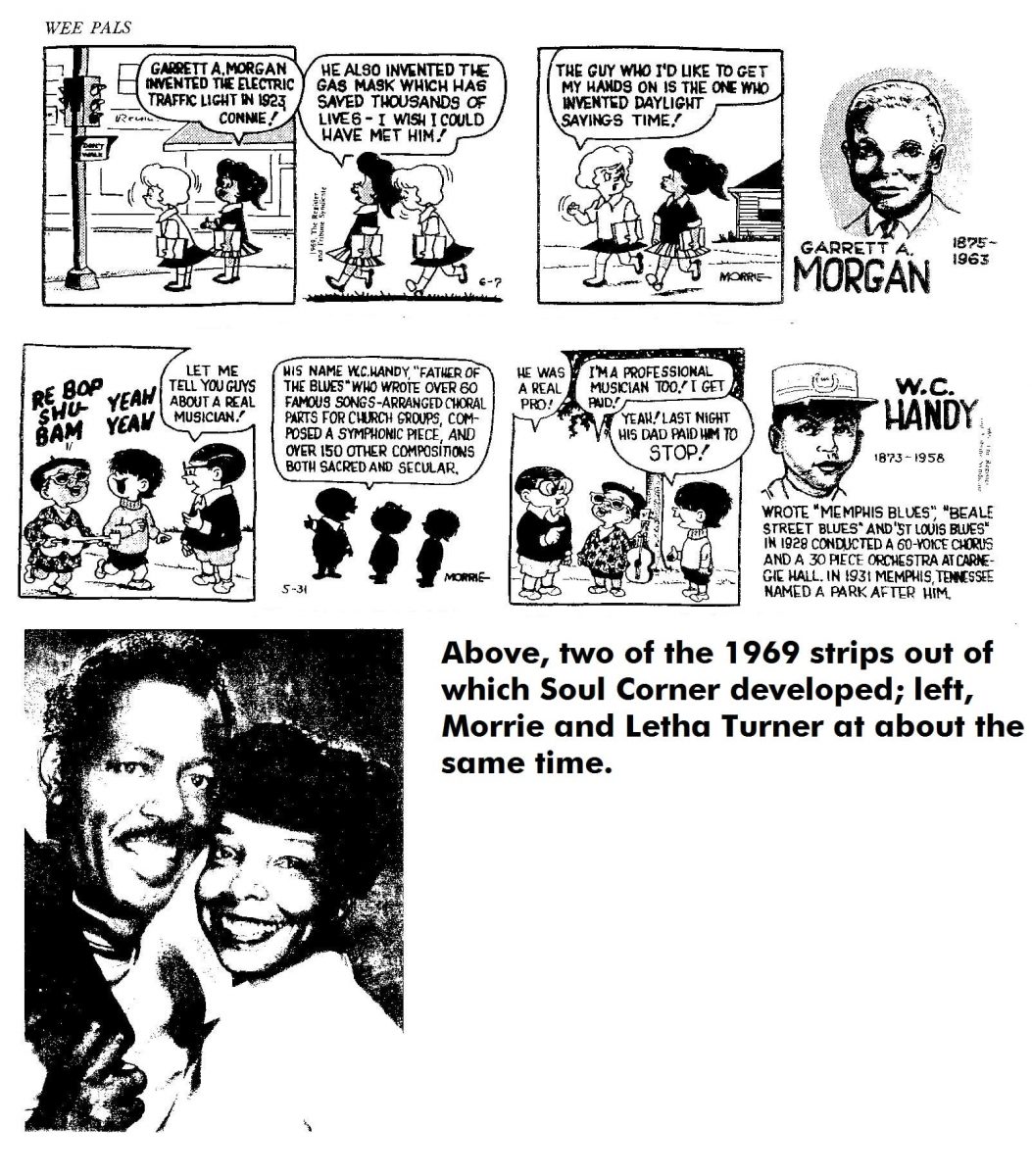

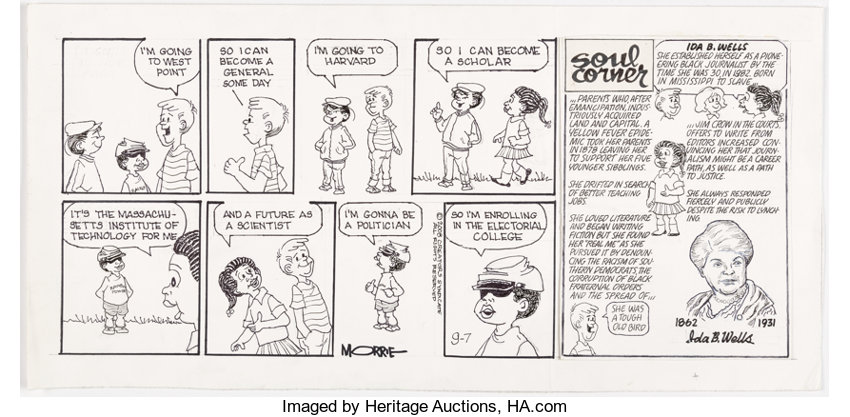

In February 1969, during Negro History Month, Turner added a new segment, Soul Corner, to accompany his Sunday comic strip of Wee Pals. Letha, Morrie’s wife, researched the details that supported this panel segment, which highlighted accomplishments of Black people, including Dr. Charles Drew, Jean Baptiste DuSable, Matthew Henson and George Washington Carver. On the Oakland Public Library Blogs, author Marco Frazier posted about this Black history segment in “Celebrating the Life of Morrie Turner on the Anniversary of Wee Pals” in February 2019. Frazier provided insight on the selection of the achievers highlighted, writing, “Soul Corner always featured deceased individuals as his strips were produced 13 weeks in advance. By the time the strip made it to print a lot could have happened in a person’s profile.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Harvey echoed the sentiment of Frazier but provided greater details of the Turners’ process in creating Soul Corner. Harvey inserted the cartoonist’s intent, “One year ago, prior to what has come to be known as ‘Negro History Week,’ I decided to herald the accomplishments and contributions of Black Americans to U.S. history via the strip.” However, the Turners quickly discovered that they knew very little, overall, about Black history but “… we slowly became educated and learned a new pride.”

In “Morrie Turner: To Say the Name is Both Eulogy and Tribute”, Harvey gave the rationale supporting the creation of Soul Corner, beyond the obvious need to educate and celebrate African-Americans about their own culture. The journalist reports that the Turners wanted to share their knowledge with all, “not exclusively with the Black child for the pride and dignity it could give him, but mainly with the deprived suburban, White child, who, we felt, needed to be made aware of the contributions of his Black brothers. We felt it necessary that in the process of learning, the child should be entertained or he would not digest the lesson; therefore, we decided that the Wee Pals characters were perfect for the task.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

By the early 1970s, Wee Pals expanded beyond the world of print and reached a new viewing audience. Wee Pals was converted into Kid Power, an ABC Saturday morning cartoon that featured the comic strip’s characters. From 1972-73, KGO-TV, a station in San Francisco, created a weekly program where Turner’s characters visited various venues. On this live program, child actors portrayed the primary characters from Wee Pals.

Turner’s vision of cultural diversity, significantly of African-Americans, motivated his White cartoonist friends to include Black characters in their own strips and cartoons. These friends included mentor, Schulz, who created “Franklin” for Peanuts; Mort Walker, who included Lt. Flap in Beetle Bailey; and Keane, who developed “Morrie” in Family Circus. The choice of the name of Bil Keane’s character was in tribute to his strong and enduring friendship with Turner. It was with Keane that Turner, via telephone, celebrated his fear, pride and joy in the election of Barack H. Obama as the first Black President of the United States. Frightened that Obama may be assassinated, he was also moved beyond words to describe the historical accomplishment. Turner soon tearfully shared with Keane, as Golden covered in Davis Enterprise, “… that he felt like an American. Keane replied that, in its own way, Wee Pals helped make the moment possible.”

For the next several decades, Turner continued to create Wee Pals. In a January 2010 KCRA news story, it was declared that “… at 86 years old, Morrie Turner still turned in one comic strip daily to Creators Syndicate … and Wee Pals has 25 million readers and is published in more than 100 newspapers.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Turner still produced politically-sharp comic panels for readers of Black publications, including Ebony. He wrote and illustrated numerous books, including Wee Pals, Nipper, Wee Pals: Book of Knowledge, Wee Pals: Staying Cool and Happy Birthday America, and his topics ranged from African-American history, inclusion and health to peer pressure, drug usage and gangs.

Throughout his life, he received numerous honors such as the Image Award from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Humanitarian Award from both the B’Nai Brith and the Anti-Defamation League organizations. From the Cartoon Art Museum and Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Library, he was gifted the Sparky Award in 2000. The name of the award was the nickname of cartoon pioneer Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts and Turner’s mentor. He was awarded by the National Cartoon Society with its Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003. It had to be extremely humbling and rewarding for Turner to have received such a prestigious award. This is especially true, considering that it was Caniff, a childhood hero, who had written him such detailed advice for cartooning when Turner was a youth. His great friend, Bil Keane, creator of Family Circus, was the presenter of the award.

Morrie Turner also was honored several times by Comic-Con including receiving the Inkpot Award in 1981 and the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award in 2012. Turner’s favorite accolade, according to the tribute article “Morrie Turner: Creator of Wee Pals Comic Strip”, written by Kate Kelly on the America Comes Alive! blog, was “… when he was asked to serve on the White House Conference on Children along with many well-respected educators.”

Honored by Children’s Fairyland, his work has been exhibited in several galleries, libraries, museums and universities throughout the United States. He continued to teach children in cartooning programs held in his local California community. Turner also mentored aspiring artists, including Black cartoonists Robb Armstrong, creator of Jumpstart; Brumsic Brandon Jr. creator of Luther; Steve Bentley, creator of Herb and Jamaal, and Aaron McGruder, creator of The Boondocks.

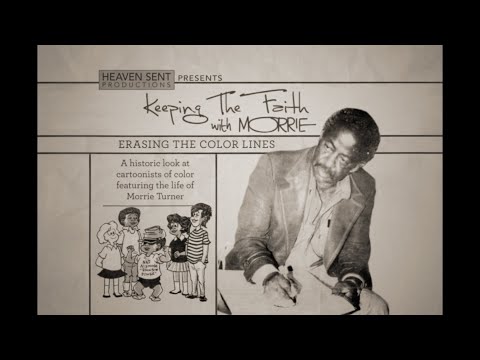

Morrie Turner was memorialized in the film, Keeping the Faith with Morrie, which documented his life. The documentary won the award for “Best Direction” in the 2001 Christian Film Festival and for “Best Documentary” in the 2002 Hollywood Black Film Festival.

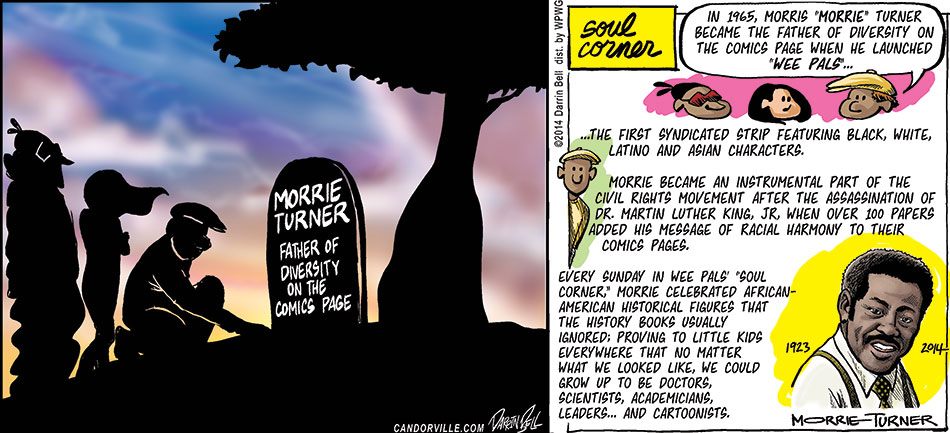

On January 25, 2014, Morrie Turner, at 90 years old, quietly passed away from chronic kidney disease at a hospital in Sacramento. Preceded in death by Letha, who died in 1994, he was surrounded by his loved ones.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

In honor of him being both the first Black person to create a nationally-syndicated cartoon strip that featured an all-Black cast of characters (Dinky Fellas) and being the first cartoonist to develop a nationally-syndicated comic strip that contained a culturally diverse cast of characters (Wee Pals), the city of Oakland, California declared November 19th as “Morrie Turner Day”.

“All the kids were different. White, Filipino, Japanese, Chinese, Black. It was a rainbow. I didn’t know that wasn’t the way it was other places. Oakland was that way before the war. We were all equal …”

~ Morrie Turner