“Known as ‘the Grande Dame of Southern Cooking’, Edna Lewis … convinced her fellow Americans to take a second look at Southern cooking while also serving as one of the first voices to reemphasize the importance of fresh, seasonal ingredients.”

~ Mark V. Reynolds, public relations, Chicago, United States Postal Service

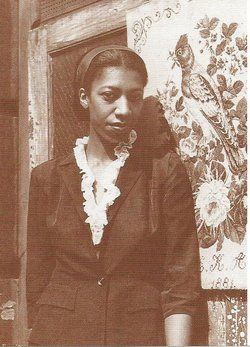

Edna Regina Lewis was born on April 16, 1913 in Freetown, a small farming community in Orange County, Virginia. Freetown was founded by three men, one of who was her grandfather, and its name was homage to their newly-attained emancipation. Her grandfather also founded the community’s first school; its classes were held in the living room of his home.

The family of Edna lived on a farm gifted to them by her grandfather. As one of eight children, Edna Lewis worked alongside her parents and siblings in farming the land. The Lewis family was involved in all aspects of farming food, from growing, foraging and harvesting to preserving, cooking and selling. Because they lacked modern amenities with which to store, cook and bake, the Lewis family, like many families who farm, had to be creative and resourceful.

Edna Lewis did not formally attend a professional school of culinary arts but learned a great deal of her skills from an aunt named Jenny. According to the biography of Lewis published by the Edna Lewis Foundation, “They used a wood-fired stove for all their cooking and didn’t have measure spoons or scales, so instead, they used coins, piling baking powder on pennies, salt on dimes, and baking soda on nickels. Lewis is said to have been able to tell when a cake was done just by listening.”

On her family’s farm, Edna Lewis fell in love with freshness and seasonality. In “Famed Cook Trying to Revive Southern Food”, written by Prue Salasky for Daily Press, Lewis lamented the vibrancy and deliciousness of Southern fare. Salasky wrote of Lewis’ concern, stating “that taste has diminished in Southern foods, thanks to out-of-season foods being shipped from all over the world and modern farming methods. ‘Raising catfish in tanks, they just don’t have that good, muddy taste …’”

When Edna turned sixteen years old, she, inspired by The Great Migration, left Freetown and moved to Washington, D.C. For the remainder of her life, Lewis held great love for the lifestyle and customs in which she was reared and actively sought to share this love with others. In her book, The Taste of Country Cooking, Edna Lewis praised, “The spirit of pride in community and of cooperation in the work of farming is what made Freetown a very wonderful place to grow up in.”

While in the nation’s capital, Lewis worked as a graphic type operator and, in 1936, supported the second presidential campaign of Franklin D. Roosevelt. When Lewis was in her early thirties, she moved to New York City. During the span of her living in Washington, D.C. and moving, Edna Lewis married Steven Kingston. Both Lewis and Kingston, a cook retired from the United States Merchant Marine, were supporters of communism.

The first position of employment Edna Lewis attained was in a laundry in Brooklyn; it involved her assignment to an ironing board. Having never ironed before, she was fired after working only three hours. Fortunately, Lewis had experience in sewing and quickly secured work as a seamstress. Creating dresses for famous and popular clients, including Dorcas Avedon, wife of celebrated photographer, Richard Avedon, and actress, Marilyn Monroe, Edna Lewis also became well-known for her own African-inspired designs.

In New York, Edna Lewis continued to be politically active, even writing for a communist newspaper, The Daily Worker, and worked a variety of jobs. She also threw dinner parties for her guests and friends, which included John Nicholson, an antiques dealer. In 1948, Nicholson opened his own restaurant, Café Nicholson, originally located at 147 East 57th St., and later at 323 East 58th Street, both on the East Side of the Manhattan borough. He persuaded Lewis to be his partner and chef. It should be noted that at that time, there were few Blacks and few women who worked as chefs in a restaurant; there were even fewer chefs who were Black women.

Nicholson, a bohemian with an affinity for luxury, was known for his connections with the socially elite. However, the autodidactic Edna Lewis prepared and served fare that Nicholson referred to as a “very simple menu and very simply presented”, as per the United States Postal Service website that featured Lewis’ biography. There was no menu but, as stated on the postal website, “An enthusiastic 1951 New York Herald Tribune article informed readers that Café Nicholson …served the same delicious meals every day, such as roast chicken with herbs.” Chocolate soufflé, for which she had become well-known, was offered as dessert.

Café Nicholson was a great success and drew many famous personalities and talents, such as Avedon; artist Salvador Dali; designer, Gloria Vanderbilt; actors Marlon Brando and Dean Martin; comedian Jerry Lewis; actresses Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich; and even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who savored her dishes. Her delicious cooking especially appealed to Southerners, including Nobel Prize Laureate and writer, William Faulkner of Oxford, Mississippi; critically-acclaimed playwright Tennessee Williams of Columbus, Mississippi; and award-winning author, Truman Capote of New Orleans, Louisiana.

Her husband was not a fan of her cooking for the elite and felt she, as a fellow supporter of communism, should be cooking for common people. In a 2004 interview with The New York Times, Nicholson reported that Lewis and Kingston would argue over the bourgeoise character of Cafe Nicholson. In the article, he reported that Kingston, “… used to always say, “This restaurant should be for ordinary people on the street. You’re catering to capitalists.’”

In 1954, Edna Lewis left the Cafe Nicholson. For the next two decades, she engaged in various activities for employment, including raising pheasants with her husband on their farm in New Jersey and acting as a docent in the Hall of African Peoples in the American Museum of Natural History on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. However, her stature as a stellar chef never diminished and in 1972, The Edna Lewis Cookbook was released by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. publishing house. Sadly, during this time of her creating her first cookbook, her husband, Steven, passed away. This book, co-authored by Evangeline Peterson, was written when Lewis was recovering from a broken leg injury. She had been encouraged to author it by Judith Jones, the cookbook editor at Knopf. The Edna Lewis Cookbook was successful and praised by iconic culinary greats, such as James Beard and M.K.F. Fisher.

Jones, however, felt the book could have been greater improved and personally involved herself with the composition of Lewis’ second book, The Taste of Country Cooking. Published in 1976, The Taste of Country Cooking featured recipes; history of African American and Southern food; and personal anecdotes. It instantly became the book Jones envisioned and was rendered a classic, by both cooks and critics. In 1979, food editor and restaurant critic, Craig Claiborne, of The New York Times exclaimed that The Taste of Country Cooking “may well be the most entertaining regional cookbook in America”.

After the release of her second book, Edna Lewis returned to cooking professionally. From the 1980s to the mid-1990s, Edna Lewis worked as a chef, including at The Fearrington House Restaurant in Pittsboro, North Carolina; Middleton Place in Charleston, South Carolina; and the historic Gage and Tollner in the borough of Brooklyn in New York City.

During this time, she founded the Society for the Revival and Preservation of Southern Food, which was the forerunner for the Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA). In 1986, Lewis adopted a young adult, Afeworki Paulos of Eritrea; he had come to the United States to further his education. In 1988, her cookbook, In Pursuit of Flavor, was released and became another best-selling book. In 1990, she also became close friends with Scott Peacock, who she met when he worked as a cook in the Governor’s Mansion in Virginia.

(No copyright infringement intended).

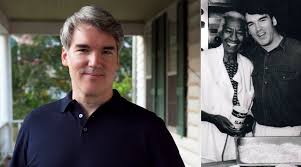

Edna Lewis retired in 1995. While she continued to advocate for traditions, significantly of freshness and seasonality, of Southern cooking, Lewis formed a close kinship with Peacock. The two would collaborate in authoring, The Gift of Southern Cooking. Released in 2003, the book was celebrated for its recipes and the authors sincere respect for and friendship with each other. Best-selling, The Gift of Southern Cooking was nominated for a James Beard Award and an International Association of Culinary Professionals Award.

It may seem that Lewis, a Black, elderly, widowed doyenne of culinary arts, and Peacock, a White, young, gay chef, have little in common. However, both worked diligently, even teaching cooking classes, to preserve the culinary traditions of Southern fare.

As Lewis aged, Peacock, following her wishes, became her caretaker; Peacock, lived with Lewis for more than six years, taking care of her as she grew frail. In a 2004 interview with The New York Times, food writer and recipient of the 1993 Grand Dame award from Les Dames d’Escoffier, Marion Cunningham, affirmed the connection between chefs, Edna Lewis and Scott Peacock. Cunningham stated, “One of the biggest goals they had was that they didn’t want to lose the classic Southern dishes, and this was the binding factor … They preached about it, and they wanted to let the country know what the South stood for.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

On February 13, 2006, Edna Lewis passed away from natural causes; she was eighty-nine years old. She died in her sleep in her home in Decatur, Georgia.

In her lifetime, Edna Lewis was the recipient of several prestigious honors, including being named in “Who’s Who in American Cooking,” by Cook’s Magazine in 1986 and given the “Lifetime Achievement Award” by the International Association of Culinary Professionals in 1990. She was the inaugural recipient of the “James Beard Living Legend Award” in 1995. The following year, she was awarded an honorary doctorate in Culinary Arts from Johnson & Wales University (Norfolk), College of Culinary Arts. In 1999, Edna Lewis was also the inaugural recipient of the “Lifetime Achievement Award” from Southern Foodways Alliance as well as was named “Grande Dame” by Les Dames d’Escoffier, an international organization of female culinary professionals.

Her recognition by the SFA was referenced in the obituary article, “Edna Lewis, 89, Dies; Wrote Cookbooks that Revived, Refines Southern Cuisine”, authored by Eric Asimov and Kim Severson of The New York Times. In it, John T. Edge, the author and director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, stated Edna Lewis’ extensive “devotion to educating a nation about the nuances of Southern cooking” prompted the SFA’s decision to grant its first “Lifetime Achievement Award” to Lewis. In the article, Edge “pointed to her recipe for shrimp and grits, a Southern classic. ‘It’s just butter and shrimp, but it requires great butter and great shrimp, and a puddle of that over stone-ground grits … This pays homage to the frugal South, but it’s also worthy of damask dinner cloth.’”

She was inducted into the KitchenAid Cookbook Hall of Fame in 2003. In 2006, the documentary, Fried Chicken and Sweet Potato Pie, was released; it celebrated her influence on American cuisine.

Posthumously, Edna Lewis was honored as an African American Trailblazer by the Library of Virginia in 2009. In 2012, the Edna Lewis Foundation, based in Atlanta, Georgia, was created. Its mission, according to its website, is rooted in “honoring, preserving, and nurturing African Americans’ culinary heritage and culture and to elevating the appreciation of our culinary excellence.” In order to meet its mission, the Foundation has developed several aspects of professional and community outreach, including providing leadership and educational initiatives and hosting an annual conference.

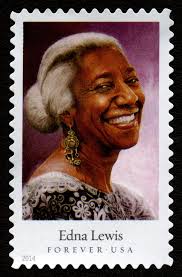

In 2014, the United States Postal Service celebrated the immense contributions of Edna Lewis to society by their creation of a “Forever” postal stamp in her honor. She is one of only five celebrity chefs immortalized on the limited edition, “Forever”, stamps; the others were James Beard, Julia Child, Joyce Chen and Edward (Felipe) Rojas-Lombard. Of those honored in the collection, Lewis was the only Black person.

In 2017, The Taste of Country Cooking experienced a dramatic increase in sales in the United States. According to Amazon, it ranked “#5 Overall” and “#3” in the “Cookbook” category on the website’s bestseller list. The reason for this intense renewed interest was due to it being highlighted in an episode of Top Chef, a cooking competition show.

As a child in Virginia, I thought all food tasted delicious. After growing up, I didn’t think food tasted the same, so it has been my lifelong effort to try and recapture those good flavors of the past.

~ Edna Lewis