“You know they call Jesus, “The Rabbi”, which is teacher. That’s how I feel about Lloyd. That he wasn’t just a director, he was a teacher. It was a big deal for him to feel that you were a part of a company, an ensemble, and he felt that that was a journey … that didn’t just come overnight”

~ Viola Davis, Triple Crown of Acting award-winning actress

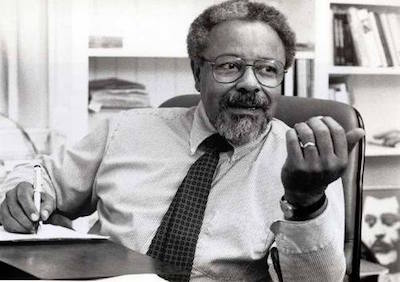

Lloyd George Richards was born in Toronto, Canada on June 29, 1919. When he was four years old, his family moved to Detroit, Michigan in order to attain a better life. His father, who hailed from Jamaica, was a follower of Black nationalist, entrepreneur and orator, Marcus Garvey, founder and President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL). Richards, who was a master carpenter, sought to gain employment in an automobile plant of Ford Motor Company, founded by Henry Ford.

When Lloyd was nine years old, tragedy struck the Richards family; his father died, having suffered from diphtheria. His mother, who did domestic work, tried very hard to keep their family intact and take care of their five children in the midst of The Great Depression. Life for the Richards was fraught with trials and poverty. When Lloyd was thirteen years old, his mother lost her eyesight. In order to support the Richards family, Lloyd and his older brother, Allan, worked odd jobs, including sweeping floors in local barber shops and shining shoes. Obituary writer Matt Schudel of The Washington Post reported Richards’ high regard for the significance of the barber shop in the Black community when Richards championed, “You’re listening in the barbershop, and you hear poetry, philosophy, sports … You’re hearing history; you’re hearing the elders speak.”

While in high school, Lloyd Richards became greatly interested in theatre arts, especially after reading the works of William Shakespeare. The Richards family believed in the value of education and, encouraged by his mother, heentered Wayne State University located in Detroit. Initially enrolled in pre-law, he followed his passion and became involved with acting and radio programming. Majoring in theatre, Richards graduated from Wayne State University in 1944.

Upon his graduation, he enlisted to serve in the U.S. Army Air Corps. There was still segregation during World War II and this corps was not exempt. Richards served in the division of African-American fighter pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen, the first division of Black pilots in the United States.

He returned to Detroit after completing his service in the military and began to work as a radio announcer and disc jockey. Whether on air in radio dramas or off air in local theatres, Lloyd Richards was becoming more skilled at his craft. He also joined an acting troupe and soon after, founded his own theatre group, to hone his talents.

Because the epicenter of theatre arts is New York City, in 1947, Lloyd Richards moved. While working to attain acting roles, he undertook jobs of menial labor, such as waiting tables and cooking. He performed in plays, including Freight and The Egghead on Broadway, in productions Off-Broadway, in roles on soap operas and in television spots. By the 1950s, he secured a stable position as an acting teacher and coach. This stability was needed, as, in 1957, Lloyd married Barbara Davenport, a dancer on Broadway. The couple would have two sons, Scott and Thomas.

It was in a drama workshop that Richards met Bahamian Sidney Poitier, another struggling actor and fellow West Indian. Poitier introduced Richards to African-American playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Poitier’s referencing of Richards as one of the best drama coaches of his era would extend beyond an introduction. The initial meeting would lead to a year-long collaboration of Richards, Hansberry and Poitier, refining the script of what would be A Raisin in the Sun. It was Richards’ first time directing.

Opening at the Ethel Barrymore Theater on March 11, 1959, A Raisin in the Sun was groundbreaking for American theater and African-American drama. The play presents the experiences of a Black family, the Youngers, living in poverty on the South Side of Chicago. After receiving an insurance payment for the death of the patriarch, each family member has a different opinion on how they wish to economically improve their lives.

The play was nominated for four Tony Awards: “Best Play” – written by Lorraine Hansberry, produced by Philip Rose, David J. Cogan; “Best Actor in Play” – Sidney Poitier; “Best Actress in a Play” – Claudia McNeil; and “Best Direction of a Play” – Lloyd Richards. The New York Drama Critics’ Circle named it the “Best Play” of 1959. A Raisin in the Sun was pioneering in that it was the first Black drama on Broadway; it is the first play on Broadway written by a Black playwright; and the first play on Broadway directed by a Black director!

After such a milestone, Richards directed and adapted of African-American works, The Long Dream, a novel written by Richard Wright, and The Amen Corner, authored by James Baldwin. He also worked on productions, including musicals, I Had a Ball and The Yearling, that were not rooted in Black culture. However, he was finding it difficult to obtain professional work directing in theatre arts and resumed to teaching acting.

In 1966, Lloyd Richards worked as a drama instructor at Hunter College and at New York University, where he headed the acting program in the School of Arts; he held this latter position until 1972. In 1968, he accepted the prestigious position as director of the National Playwrights Conference at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center. Held in Waterford, Connecticut, this annual summer workshop hosted well-known and up-and-coming persons involved in theatre arts. They ranged from playwrights, including Athol Fugard OIS of South Africa, Wendy Wasserstein, David Henry Hwang and August Wilson; and actors, such as James Earl Jones. At this workshop, guests could bring a draft of their work and have it fine-tuned to become a finished piece. This was made possible due to the guidance of industry professionals, including critics, who served as resident experts. During the thirty-one years that Richards led as the workshop’s director, numerous plays, such as Agnes of God and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, that came to the O’Neill Theater Center became classics on Broadway.

From 1979 until 1991, Lloyd Richards served as dean of the esteemed Yale School of Drama and artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theater at Yale University, an Ivy League institution of higher learning. As with his previous positions, Richards utilized these positions to cultivate the talents of future playwrights, directors and actors, including husband-and-wife Courtney B. Vance and Angela Bassett, and Charles S. Dutton.

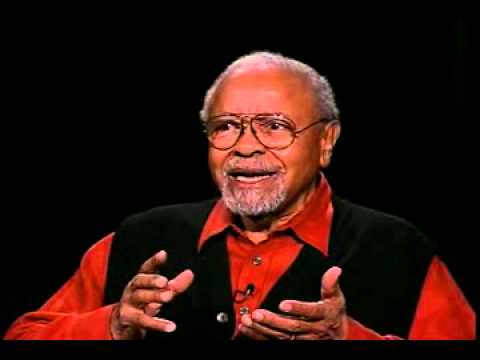

Praises of his contributions are immense and include that of Rocky Carroll, who, in the American Masters documentary, “August Wilson: The Ground on Which I Stand”, regaled, “Lloyd was a powerful man … because his ability to nurture talent, not feel the pressure, not feel the need to play the role of director … but to really understand and get a sense of what makes an actor tick, what their strengths and weaknesses were …” In the biography on Lloyd Richards of the National Visionary Leadership Project, actor, writer and director Bill Duke assured, “I can say to you quite honestly that without Lloyd Richards, I would not be in this business.” In that biography, actress Mary Alice, who won a Tony Award – “Best Featured Actress in a Play” and a Drama Desk Award – “Outstanding Featured Actress in a Play” for her performance as Rose Maxson in Fences, echoed Duke’s sentiment about Richards. Alice raved, “He is the one, the most important person, outside of myself, in my career.”

At Yale, Lloyd Richards directed classic and contemporary works and created Winterfest, an annual festival in which four new plays were performed. Richards encouraged playwrights to become involved with the rehearsal process but Richards’ signature on any work he directed was that he kept his own influence from permeating it.

Richards became known for his wise and reserved approach, as Dutton shared with Campbell Robertson in The New York Times, “He’d say one word or one sentence, and it would just open the door to a whole world in approaching the character.” In the American Masters documentary, actors commented on the quiet brilliance of Lloyd Richards. Actor Stephen McKinley Henderson declared, “He’s like Socrates, man … he’s like one of the great, the great teachers … and he would question, so he had this Socratic way that he would question, so that you would arrive at the answer, rather than telling you something.” Actress Ella Joyce recounted, “He didn’t talk a lot … but when he did say something, it was like E.F. Hutton, you gotta listen … y’know, whatever’s coming from him was like gold.”

Aside from leading the summer workshops at the O’Neill Theater Center as well as the drama school and theater director at Yale University, Richards was a member of both the Playwrights Selection Committee of the Rockefeller Foundation and of the New American Plays program of the Ford Foundation. He also served as the president of the Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers. These positions provided numerous opportunities in which Richards could discover and develop new content and talent. Perhaps the most notable influence he had on a playwright was upon August Wilson. Their collaboration, according to the National Visionary Leadership Project biography, is “one of the most significant director-playwright relationships in modern American theater.”

Lloyd Richards met August Wilson at the summer workshop. Richards edited and polished the draft Wilson submitted; it would become the script for Wilson’s first major play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Directed by Lloyd Richards, Wilson’s play had its first staged reading in 1982 at the O’Neill Theater Center. Working together on its development for two years, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom opened at the Yale Repertory Theater in April 1984 and premiered at the Cort Theater on Broadway in October 1984. Having a run of 276 performances, in 1985, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was nominated for three Tony Awards: “Best Play”; “Best Featured Actor in a Play” – Charles S. Dutton and “Best Featured Actress in a Play” – Theresa Merritt.

After this success, Lloyd Richards and August Wilson would continue to collaborate for more than a decade. Wilson undertook and accomplished an incredible feat, creating what is known as The Pittsburgh Cycle or The Century Cycle. This cycle is a series of ten plays that document each decade of Black life, primarily in the Black community of The Hill District in Pittsburgh, during the twentieth century. After Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Richards directed Fences, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, The Piano Lesson, Two Trains Running and Seven Guitars.

August Wilson won both the 1987 Pulitzer Prize for “Drama” and the 1987 Tony Award – “Best Play” for Fences; Lloyd Richards won the 1987 Tony Award – “Best Direction of a Play”. The play was first developed at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center’s 1983 National Playwrights Conference and premiered at the Yale Repertory Theater in 1985. August Wilson won the 1990 Pulitzer Prize for “Drama” for The Piano Lesson, which also opened at the Yale Repertory Theater. Both Fences and The Piano Lesson won, respectively, the Drama Desk Award for “Outstanding New Play” in 1987 and 1990.

During his time in directing plays, he also worked in directing television, including a segment of Roots: The Next Generation, Bill Moyers’ Journal and a film about African-American singer, actor and activist Paul Robeson, who inspired Richards. He also directed Paul Robeson, a theatre production about the life and legacy of Robeson.

In 1991, Lloyd Richards retired from his positions at Yale University and later from his role at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in 1999. Richards became a professor emeritus at the Yale School of Drama and served on several boards of theatre arts, including the National Endowment for the Arts.

On June 29th, 2006, Lloyd Richards, suffering from cardiovascular disease, died from heart failure at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. He passed away on his 87th birthday.

The recipient of numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts Lifetime Achievement Award by the U.S. Congress in 1993 and The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize gifted by their trust in 2002, Lloyd Richards was also inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame. His impact on African-American culture and American theatre arts is immeasurable.

“If you, at any point, say, ‘Oh! I see the director in that’, then it’s wrong. Because it isn’t about being a director; it’s about the material itself and making it live … and making it seem so simple and so easy, that you don’t think a director has been there at all. That’s my job.

~ Lloyd Richards

For greater enlightenment...

-

Lloyd Richards 1991 - American Academy of Achievement

-

The Director (Career Guides) of American Theatre Wings

-

August Wilson’s Conversation: The Lloyd Richards Effect

-

Classic Clips: August Wilson & Lloyd Richards on “Fences” (1987)

-

A Raisin in the Sun (1961) ORIGINAL TRAILER [HD 1080p]

-

Fences Trailer (2016) - Paramount Pictures