Located at 1411 W Street, SE in the Anacostia neighborhood in southeast Washington, D.C., the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site contains the home and estate of Frederick Douglass. Douglass, who lived from February 14, 1818 (self-given) and passed on February 20, 1895, is considered to be one of the most eminent African-Americans of the 19th century. The impact of Douglass, who was an abolitionist, statesman, human rights activist and social reformer, was massive. According to the biography of Douglass in Encyclopedia Britannica, “… his oratorical and literary brilliance thrust him into the forefront of the U.S. abolition movement, and he became the first Black citizen to hold high rank in the U.S. government.”

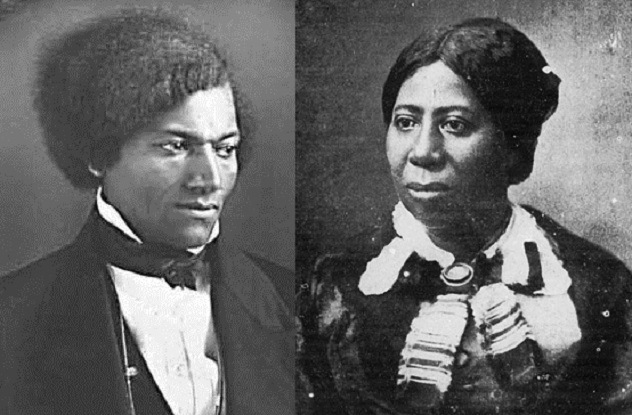

In 1872, Frederick Douglass moved from Rochester, New York to live in Washington, D.C. In 1877, Douglass paid $6,700 to the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Bank for a house and 9 and ¾ acres of land. The following year, Douglass purchased an additional 5 and ¾ acres of land from Ella R. Talburtt. In autumn 1878, he and his wife, Anna Murray Douglass, would move into their home located in a neighborhood that is presently called Anacostia. Anna Murray Douglass was an African-American abolitionist and member of the Underground Railroad. She and Frederick were married from 1838 until her passing in 1882; they had been married for 44 years.

This image is sourced from Choptank River Heritage (No copyright infringement intended.).

Because the house sat high on a hill, surrounded by cedar trees, Frederick and Anna named their home, “Cedar Hill”. The couple expanded the house from 14 rooms; Frederick would, ultimately, develop the structure to house 21 rooms. Situated east of the Anacostia River, the view from the hilltop home spans the skyline of our nation’s capital, including of the Capitol Building.

Cedar Hill was the final home of Frederick Douglass, who was preceded in death by his wife, Anna. Approximately seventeen months after the passing of Anna, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a Caucasian suffragist and abolitionist who was twenty years younger than he. Their marriage caused controversy because of the differences in their races and ages. Frederick Douglass would live at Cedar Hill, whose décor detailed much of his work, interests and travels, for seventeen years. As it states on a webpage of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, “His home provided the backdrop to his active political and warm family life. The spacious estate and well-furnished rooms are a testament to Douglass’ lifelong struggle to overcome entrenched prejudice.”

Visitors to this site, which is maintained by the National Park Service, will experience the home as it was when the Douglass family lived there. Items, such as his violin, his Panama hat, the china closet, his library of greater than 1,000 volumes and the checker set, illustrate their lives and acculturation. Inside Cedar Hill are Roman statues; busts and paintings of Douglass; art depicting events and themes in African-American history; portraits of family and friends, including John Brown; and gifts from those, such as antislavery author Harriet Beecher Stowe and President Abraham Lincoln, close to the Douglass family. There are numerous images of him throughout Cedar Hill, as Frederick Douglass was one of the most photographed persons in American history .

The house was originally built between 1855 and 1859 for John Welsh Van Hook, an architect from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. During the time that Van Hook resided there, it was expanded and grew from 6 rooms to 14 rooms. In 1854, Van Hook partnered with John Fox and John Dobler and formed the Union Land Association; the home housed offices for the three partners. During their partnership, 100 acres of farmland was bought in order to develop a new subdivision, “Uniontown”; this subdivision is presently known as Anacostia.

With the Douglass family moving in, their plans for expansion were set in motion. A new kitchen, which included a coal-burning stove, was added to the south wing and the former kitchen became a dining room. On the west side of the home, partitions were removed in order to create three smaller bedrooms. The attic was finished to provide five additional rooms. After their move-in, renovations and additions, including of a new library and another bedroom, continued. In all, Cedar Hill contains on the first floor: the Entrance Hall, the East Parlor, the West Parlor, the Library, the Dining Room, the Kitchen, the Pantry and the Laundry Room. On the estate’s second floor are the bedrooms, with the men’s room being located on the east side of the upstairs hallway and the women’s rooms being on the west side of the upstairs hallway: Frederick Douglass Bedroom; Men’s Guest Bedroom; and Helen Pitts Douglass Bedroom; Anna Douglass Bedroom; and Lady’s Guest Bedroom. On the west side is a bedroom for Haley George Douglass, a grandson of Frederick and Anna.

In 1886, Frederick Douglass left much of his investments and real estate to the four adult children that he and Anna shared; Cedar Hill and most of his personal property was left to Helen. After Frederick’s passing in 1895, the following year, Helen worked with the National League of Colored Women in order to garner support to establish Cedar Hill as a historic site. In 1900, the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association (FDMHA) was chartered by Congress. This non-profit association was formed by Helen Douglass in order to, as per the site’s website, “… preserve to posterity the memory of the life and character of the late Frederick Douglass …” and “… collect, collate, and preserve an historical record … of the anti-slavery movement” at Cedar Hill.

When Helen Douglass passed in 1903, Cedar Hill was bequeathed to FDMHA. The home had a $5,500 mortgage. The president of FDMHA, Archibald Grimke, and leaders, including Booker T. Washington, sought donations and government assistance to preserve Cedar Hill. In 1916, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), led by its president, Mary B. Talbert, agreed at the organization’s biennial meeting to pay the remaining debt of $4,000 in time for the centennial of Frederick Douglass’ birth. In 1918,

the NACW honored their agreement and at their biennial meeting held in Denver, Colorado, donor Madam C.J. Walker burned the mortgage paperwork in front of a huge audience of supporters. For the next four years, the NACW raised and spent, according the national site’s webpage, “… an estimated $11,000 ‘to restore, rehabilitate and beautify the home’, in the words of Hallie Q. Brown.” Brown served as the president of the NACW from 1920 to 1924. An African-American educator, writer, activist and elocutionist, Brown, as a guest of the Douglass family, stayed at Cedar Hill whenever she visited D.C.

In 1922, the association formed a partnership with the NACW to undergo the first restoration of the home. At the ceremony celebrating its reopening, Robert Moton, president of the historically Black college, Tuskegee Institute, was the keynote speaker. Joseph Douglass, a grandson of Frederick and Anna, provided a music performance on his violin. Six years later, a cottage for FDMHA employees was constructed in back of the mansion. In 1938, the National Youth Administration, led by Mary McLeod Bethune, restored the grounds and pathways and the Works Progress Administration began to catalog personal items of the Douglass family to create a museum collection.

The federal government became involved in the preservation of Cedar Hill when, in 1962, President John F. Kennedy signed Public Law 87-633, rendering the estate to become a unit of the National Park Service. Two years later, the FDMHA deeded Cedar Hill, the papers of Frederick Douglass and the museum collection as a “gift to the United States of America”. A second restoration, which took almost ten years, was completed in 1972 and was re-opened to the public. In 1982, a newly-built Visitor Center was opened to the public. In 1988, legislation was passed by Congress to designate the Frederick Douglass Home as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. In 2004, the third restoration was undertaken; the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site was opened again to the public in 2007.

At the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, the only way to gain entry is to be on a guided tour. The interpretive tour is led by rangers of the National Park Service and occur at scheduled times. The tour, which lasts approximately thirty minutes, are of the home’s first and second floors. The tour may be standard, in which the maximum is ten people, or group, which is a maximum of sixty people. Reservations are not required for a standard tour but are highly encouraged, as the tours quickly sell out. Reservations are required for a group tour. Tickets may be reserved by telephone or online; there is a $1.00 fee for each reserved ticket and reservations must be made at least one day prior to the anticipated tour date. School groups are simply charged a $10.00 fee. Tickets must be collected at the Visitor Center before the tour begins.

Because it a historic site, there are rules to which visitors must be adhere. As stated on the website of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site:

- “Visitors cannot join a tour after it has entered the historic house

- Strollers, tote bags, backpacks, and other large bags are not allowed in the historic house

- Eating, drinking, chewing gum, and smoking are not allowed in the historic house

- Photography is permitted, but the flash must be off to protect light-sensitive objects”

The Frederick Douglass National Historic Site also provides virtual tours of its site in “Museum Management Program” on their website and also on Google Cultural Institute. The site provides professional development, educational initiatives and educational programming, including lesson plans, suggested reading lists and an annual oratorical contest.

There is a bookstore located in the Visitor Center that carries the works of Fredrick Douglass. Additionally, it has available for purchase books and products centered upon Douglass and topics such as African-American culture, slavery, the Underground Railroad and emancipation.

This is surely a site that will add greater depth in understanding one of the greatest African-American leaders in history!