“Any lasting contribution that Kelly made … is dominated by the singular significance of his ethnicity. Kelly was African American and that fact played prominently in his designs, in the way he presented them to the public and in the way he engaged his audience. No other well-known fashion designer has been so inextricably linked to both his race and his culture. And no other designer was so purposeful in exploiting both.”

~ Robin Givhan, fashion editor, Washington Post

Patrick Kelly was born to Danie and Letha Kelly on September 24, 1954 in Vicksburg, Mississippi. His father worked in several different capacities, including as a cab driver and insurance agent, and his mother, who held an advanced degree, was employed as an educator of home economics. When his father left their family, Patrick’s grandmother, Ethel Rainey, often stepped in his stead to co-parent Patrick. Patrick’s mother, grandmother and his aunt, Bertha, who taught Patrick how to sew, had profound effects on him, his life and his vision.

It was his grandmother who indirectly inspired him to become a fashion designer. She worked as a domestic in the home of a White family and on one particular occasion, his grandmother brought home a fashion magazine. When Patrick, who was about six years old, inquired about the lack of African-American women featured, she explained that designers did not have time, i.e. interest, for Black women. This omission would motivate Patrick to correct this by creating his own designs for women who looked like the women in his life.

Kelly, having taught himself to sew, and by the time he was in junior high, he had begun to create dresses for girls in his neighborhood. He expanded his repertoire to dress windows of department stores and sketch for advertisements carried in newspapers by the time he graduated high school, where he won superlatives “Friendliest Boy” and “Best Boy Dancer”. Upon graduating in 1972, he moved to the nearby city of Jackson in order to attend Jackson State University. At Jackson State, Kelly, on scholarship, studied African American history and art history. However, after matriculating two years, he decided to move to Atlanta for better opportunities that would allow him to become involved in fashion design and live in an environment that was much more favorable to African-Americans and their advancement.

While in Atlanta, Patrick Kelly performed various tasks, including sorting clothing at a thrift store of AMVETS, an organization that supported American veterans; and decorating the windows of Rive Gauche, a boutique of Yves Saint Laurent, in order to sustain himself. Kelly felt a sense of service in both of these capacities, as the former assisted those, like African-Americans, who often had been forgotten and excluded by society; the latter was performed as volunteerism. This work also spurred his creativity. From AMVETS, he had access to an ever-expanding inventory that often contained designer clothing and was constantly changing. When he secured clothing that appealed to him, he would re-invent them, adding his unique flourishes, and sell them with his own items. He was soon offered a full-time position to work at Rive Gauche, which provided exposure to those established in the fashion industry. During this time, Kelly also opened his own store which sold vintage clothing and items and worked as an instructor at Barbizon Modeling School.

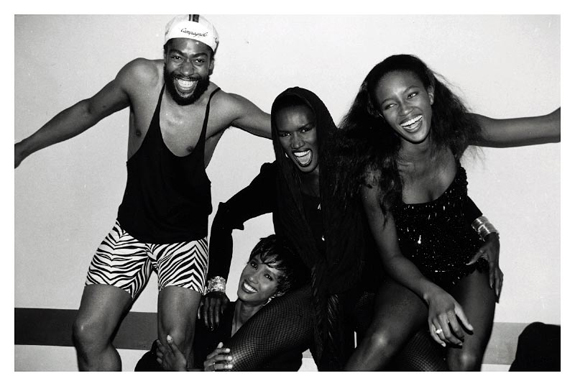

At Barbizon, he befriended several models, including future Black icons of modeling, Iman and Pat Cleveland. In 1976, in Atlanta, Iman walked her first American runway sporting a Patrick Kelly design. He actually met Cleveland in 1979 when she modeled in an Ebony Fashion Fair fashion show held in Jackson, Mississippi. Cleveland, who adored his designs, encouraged him to move to New York City, the fashion capital of the United States, in order to become truly involved in the world of style.

Kelly moved to New York and enrolled in Parson’s School of Design. However, he struggled greatly to earn a living. As he had done in Mississippi and Georgia, he continued to design and sell his own creations. Later that year, Kelly ran into Cleveland again. Understanding the difficulty in trying to attain success in the fashion industry, she provided him with another suggestion: he should emulate his idol, Josephine Baker, and move to Paris, France, the fashion capital of the world.

Obviously, Kelly could not afford to move to Paris, as he had not even become economically stable in New York City. He dismissed the possibility of living in Paris and agreed to meet Cleveland later that afternoon at a hair salon. Cleveland never appeared, but waiting for him was a one-way ticket to Paris. Anonymously gifted, Kelly took immediate advantage of his new-found opportunity and moved to Paris. Although the sender’s identity was unknown, Cleveland believed that he knew she was the benefactor.

In Paris, Patrick Kelly enjoyed greater success, including attaining a position as a costume designer for Le Palace, a popular nightclub. Even though he barely spoke French and lacked official papers to legally work, he accepted a freelance position to work with designer Paco Rabanne. Rabanne also leased an apartment for him on the Rue des Sts. -Pere.

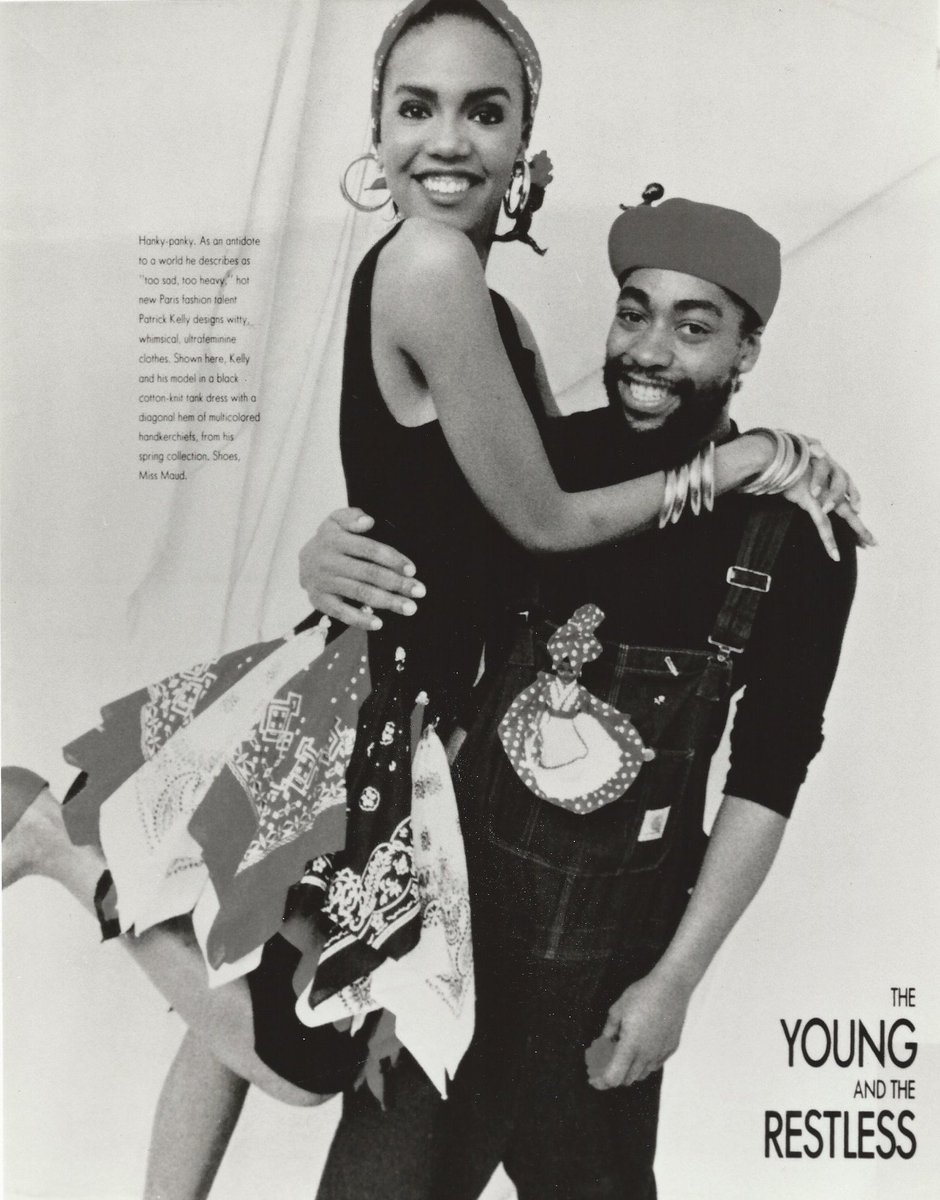

Sharing an apartment with a model friend/assistant, Liz Goodrum, he continued to work towards his vision of becoming an established fashion designer. Using a Singer sewing machine, Kelly constructed and completed his designs, which were becoming increasingly recognizable. His designs included, most notably, form-fitting dresses of jersey that were vibrant with color and accessories of brightly colored bows, grosgrain ribbons, bandannas and multicolored buttons. The button would be one of Kelly’s signatures; it was incorporated in honor of his grandmother, who often utilized buttons in mending his clothes when he was a young boy.

In 1983, Kelly met Bjorn Amelan, a successful agent for photographers such as William Klein. The two became great friends and would ultimately become partners in business and life. Having fallen ill from Crohn’s disease, Kelly lost his position with Rabanne. To earn a living, he catered Southern cuisine and put on guerilla runway shows, featuring Black models in his designs, in the streets of Paris. Drawing a devoted base of admirers, in 1984, Kelly and Amelan met Françoise Chassagnac, a former model who introduced the couple to the owners of Victoire, an exclusive boutique in Paris. In the boutique, the owners produced Kelly’s line and he managed his own workshop and showroom. In 1985, Kelly and Amelan, would collaborate to create the label, Patrick Kelly Paris. Under this label, they designed for international brands, such as Benetton, and the Right Bank, a boutique that caters to consumers of the upper echelon.

That same year, Kelly was profiled for an unprecedented six pages in the French edition of Elle. This occurred because the owners of Victoire were friends with several people who worked at the French magazine. Editor-in-chief Nicole Crassat, who had been fired, was serving her days at the fashion and lifestyle periodical. Her swan song was this February 1985 issue, which featured a lay-out on Kelly and his collection.

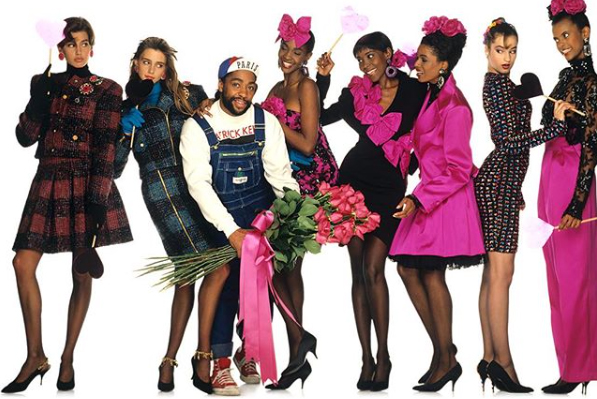

This international magazine coverage led to his increased growing popularity. Kelly began to design couture clothing for celebrities including Jessye Norman, Cicely Tyson, Grace Jones, Paloma Picasso, Bette Davis, Isabella Rossellini and Madonna. He also collaborated with David Spada, a jewelry designer. Their collaboration involved what would be one of Kelly’s most well-known pieces: a banana skirt ensemble that was inspired by African-American expatriate, acclaimed entertainer and Croix de Guerre recipient, Josephine Baker.

Referenced as “Le mignon petit noir Americain” (the cute, little Black American) and “The King of Cling”, Patrick Kelly outgrew the Victoire boutique and entered into a new business agreement with Ghinea, an Italian manufacturer. Being more affluent, he hired a small staff, which was supported by volunteer assistants.

In 1987, Patrick Kelly, who had been interviewed by Gloria Steinem on NBC’s Today Show, was introduced to Linda Wachner by Steinem. Wachner was the chief executive officer of Warnaco, an apparel manufacturer. Although the designer and CEO were in continuous talks regarding a possible partnership, it was the support of acting legend, Bette Davis, that confirmed Wachner’s decision to work with Kelly. Davis, who appeared on The David Letterman Show wearing a fitted dress in which the bodice contained a heart comprised of multiple vivid buttons, solicited viewers for financial support of Kelly. Kelly and Davis met in December 1986 when Katherine Schumer, an American assistant of Kelly, brought her former employer, Bette Davis, to his Christmas dinner.

Linda Wachner and Patrick Kelly entered into a business deal in which he signed a $5 million contract to create a clothing line for Warnaco. The manufacturing of his designs by Warnaco placed Kelly’s clothing in stores, such as Henri Bendel, Bergdorf Goodman, I. Magnin and Bloomingdale’s, throughout the world. Adding to Kelly’s ascension in the fashion industry were two licensing deals with Vogue Patterns and Streamline Industries for his large buttons. Between these deals, the business revenue of Kelly grew to be greater than $7 million annually.

As his sales grew, so did his creativity. On his designs, Patrick Kelly inserted images of hearts and embroidered lips. He also gave even greater homage to his African-American, Southern heritage, of which he was extremely proud. He incorporated flowers, such as gardenias and magnolias, but also reclaimed iconography that has been historically used to denigrate Blacks. His designs included red, polka-dotted bandannas seen on Mammy figures and watermelon brooches. His designs even paid tribute to African-American entertainers such as jazz singing legend, Billie Holiday.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

Kelly created lapel pins that featured the face of a Black baby doll, derisively referred to in history as a “golliwog”. He would disseminate his pins to all he met and it’s estimated that he gifted 800-1,000 pins monthly. Kelly, who had a collection of more than 6,000 Black dolls originating from numerous eras of American history, wanted to found his own museum of Black memorabilia. By embracing the negative stereotypes, he sought to restore the original truths, dignity and beauty of Blacks. Being able to present these alternative interpretations was of vital importance because Kelly wanted to remind all of how African-Americans survived and thrived beyond the most horrific times in contemporary global culture. He endeavored to use these historical props of racist propaganda to empower.

In “Patrick Kelly’s Radical Cheek: In New York, a Designer’s Guise and Dolls” published in the Washington Post, fashion editor and Pulitzer Prize winning author, Robin Givhan made the following observation, “The pieces on display from Kelly’s vast collection of black memorabilia are as important as his garments. Kelly accumulated more than 8,000 examples of advertising, dolls, knickknacks and household products that employed racial stereotypes, caricatures and slurs. His collection includes Mammies, pickaninnies, Topsys and golliwogs. Kelly enthusiastically embraced all of the clichés, both good and bad. He was as enraptured of black icons as he was of racist propaganda. The show features Diana Ross and Michael Jackson dolls, and Josephine Baker posters juxtaposed with old boxes of ‘darkie toothpaste’.”

In “The Secret History of Patrick Kelly” published by Dazed, journalist Stuart Brumfitt wrote of the Kelly exhibition presented by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2014. In the article, he reported of the exhibition’s curator, Dilys Blum, that Kelly “…wanted to make wearable clothes that would make people happy, but ‘at the same time, he subverted not only fashion, but also stereotypes, particularly in regard to race. He played to such assumptions while undermining them. He kept people guessing.’ He handed out racist pickaninny dolls for White society ladies to pin to their lapels, designed a watermelon hat to be worn by a Black model (the watermelon is an old symbol of racist iconography in the US – Kelly was reclaiming it) and the logo he splashed across his boutique bags was the cartoonish face of a golliwog, an image he was beginning to make his own.”

With titles of pieces such as “Pearls and Popcorn”, “Lycra Dresses and Spare-Ribs” and “Families, Especially Grandmothers and Mothers”, it is evident what Patrick Kelly felt was important and valuable. In the article of Givhan, that included discussion of the 2004 exhibition dedicated to Kelly that was curated by the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Amelan’s reflection was recalled, “While he loved Madame Gres and Yves Saint Laurent, he’d say that in one pew at Sunday church in Vicksburg, there’s more fashion to be seen than on a Paris runway.” He celebrated women of all sizes and shapes and even included a model who was eight months pregnant in one of his runway shows.

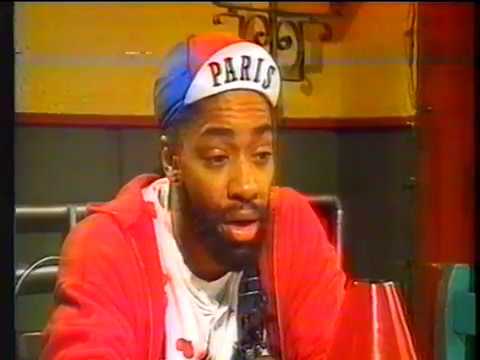

His love for his cultural and regional roots was always shown in his own personal wardrobe. He famously wore denim coveralls, colorful shirts and an upturned cyclist cap, which was often emblazoned with “PARIS” on it. Extremely outgoing, he, in his fashion “uniform”, started his design shows by spray painting a large red heart on his runway’s backdrop. He was known for his engaging personality and often refrained from sharing his age as he hoped to remain “the new kid on the block”. Though he had a youthful spirit, he was an astute entrepreneur and immensely talented designer.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1988, with the advocacy of designer Sonia Rykiel, Patrick Kelly was inducted into the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode; he would be the first Black person and first American admitted into the exclusive French organization of designers who created ready-to-wear. His brand, Patrick Kelly Paris, would be placed alongside established brands such as Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel, Lacroix and Christian Dior. Because he was a member of this elite trade association, he was able to present his fashion shows at The Louvre. According to his biography in Encyclopedia of World Biography, his first show “True to Kelly’s fun style … was a spoof on the Mona Lisa, featuring models carrying oversized gold frames in front of their faces.”

Despite these successes, Kelly would never experience the long-term impact of his accomplishments. In late August 1989, he was admitted into the Hotel Dieu hospital. He and Amelan kept the reason, complications from AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), for his hospitalization quiet. Because of the negative stigma that was associated with his condition and the desire to protect their business interests, Kelly and Amelan did not disclose that Kelly was suffering from AIDS. However, in October 1989, Wachner visited Kelly when he was unable to present the Spring 1990 show. Easily discerning his conditions and forthcoming inability to uphold his part of the arrangement with Warnaco, the deal between Kelly and Amelan with the fashion conglomerate was legally severed.

On January 1, 1990, Patrick Kelly passed away; he was only thirty-five years old. In “Delta Force” of The New York Time Magazine, Horacio Silva reported of Steinem’s eulogy for her friend, writing “‘He was an outsider who brought the outside with him,’ Steinem read in a shaky voice, ‘and then eliminated the outside-inside division for everyone. Instead of dividing us with gold and jewels, he unified us with buttons and bows.’”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Survived by his mother and Amelan, Kelly is buried in the 50th division of Paris’ Pere-Lachaise cemetary; his tomb features engraved images of a golliwog and a red, heart-shaped button.

Following his passing, many aspects of potential future business, including for a perfume; a bespoke menswear line; a collection of furs; and accessories such as sunshades and jewelry, would be abandoned. The production of an autobiographical film on Kelly never occurred. The museum he wanted to develop to house his Black memorabilia collection has yet to be realized.

However, the creative impact of Patrick Kelly is profound and his love for African-American culture was unending. He would influence future African American designers, including Patrick Robinson, and Black artists such as Kara Walker. The designs of Patrick Kelly were displayed on both the East and West Coast, at, respectively, the Black Fashion Museum in Washington, D.C. and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In 2004, The Brooklyn Museum of Art presented Patrick Kelly: A Retrospective. This exhibit, containing materials from the Kelly estate, featured sixty ensembles, items of his Black memorabilia collection and photographs from his life as a fashion designer. Ten years later, the Philadelphia Museum of Art displayed Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love, in which eighty ensembles were gifted to the museum by the Kelly estate. In 2016, Jackson State University, where Kelly attended college, presented Patrick Kelly: From Mississippi to New York to Paris and Back. In 2017, this exhibit, which contained twenty-four of his designs, premiered in Vicksburg, Kelly’s hometown.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The two repositories of Kelly’s garments are the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Jackson State University, whose collection involves approximately two-hundred and fifty items. Additionally, there are materials, including his sketchbooks as well as videos of his runway shows, interviews and memorial service, of Patrick Kelly that are held in The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the Harlem community of New York City.

“One very intelligent woman said she didn’t like the Aunt Jemimas because they reminded her of maids. I said, ‘My grandmother was a maid, honey.’ My memorabilia means a lot to me.”

~ Patrick Kelly