“… (he) opened up my eyes to the fact that I came from an old people, older than slavery, older than the people who oppressed us … Arthur Schomburg, more than any other single human being, set me in motion in the pursuit of a career as a teacher of history.”

~ John Henrik Clarke, historian, Pan-African & Africana studies pioneer

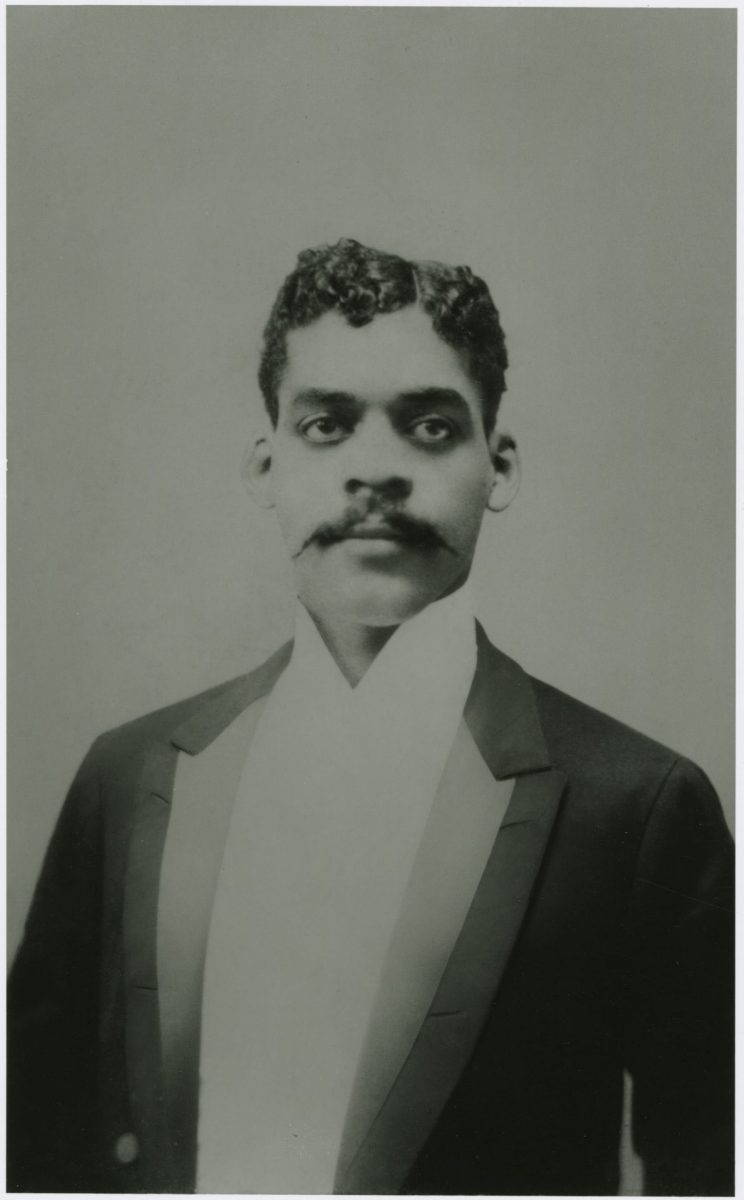

On January 24, 1874, a baby boy was born to Carlos Federico and Maria Josefa Schomburg in Santurce, Puerto Rico; four days later, he would be christened Arturo Alfonso. His father was a Puerto Rican merchant of German ancestry and his mother was a freeborn Black midwife from St. Croix, Danish West Indies. As a young boy, he spent time with tabaqueros, or cigar workers in a local factory. At the factory, a man would read aloud the news, novels, politics, speeches and other writings and from there, his love for learning grew.

When Arturo was in the fifth grade, his teacher told him that Blacks had no history, heroes or accomplishments. Because he believed otherwise, Schomburg was determined to know the truth. He would spend the rest of his life discovering, documenting, curating and collecting materials, including print, art and music, on the great and immense contributions made by persons of the Africa Diaspora.

After studying commercial printing at Instituto Popular and Africana literature at St. Thomas College, he immigrated to New York City in 1891. Only seventeen years old, Schomburg settled in the Harlem community of the Manhattan borough. He brought with him letters of reference from various cigar makers and from Jose Gonzalez Font, for whom Arturo worked as a typographer. As he did in Santurce, he spent time with local cigar makers, sharing their activism for Puerto Rico and Cuba to be free from Spanish rule. He joined cultural and political organizations that demanded independence from Spain’s imperialism, including the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico and sent letters to the editor of the newspaper, Patria.

The following year, Arturo Schomburg co-founded Las Dos Antillas, another Caribbean cultural and political organization that supported the two island countries’ independence from European colonialism. He was also the secretary of Las Dos Antillas. In 1892, he, having become a Mason, joined El Sol de Cuba Lodge no. 38; it would later be renamed “Prince Hall Lodge no. 38”, to honor the founder of Black Freemasonry in the United States.

However, with the failed revolution in Cuba and the cession of Puerto Rico to the United States, Schomburg became disillusioned. Adding to this, was the racial discrimination he experienced within America. Although he would Anglicize his first name to “Arthur” in 1895, he proudly referenced himself as “Afroborinqueño”, which means “Afro-Puerto Rican.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Also, in 1895, Arturo Schomburg married for the first time; in his lifetime, he would wed three times and each wife’s first name was Elizabeth. His first wife was Elizabeth Hatcher and she, as a participant of The Great Migration, had arrived in New York City from Virginia. Together, they had three sons: Maximo Gomez, Kingsley Guarionex (the middle name being an alias he used when he wrote letters to Patria); and Arturo Alfonso, Jr., who passed away when he was an infant. In 1900, Elizabeth died at an early age, leaving behind Arturo to rear their two sons.

In 1902, Arturo married Elizabeth Morrow Taylor, with whom they had two sons: Reginald Stanfield and Nathaniel José. After she passed, he, in 1914, married for a third time; his wife was Elizabeth Green. Together they had three children: Fernando, Dolores Marie and Placido Carlos. Even though he was proud of his heritage, he did not allow his children to speak Spanish, as he wanted them to view themselves as Americans.

Desiring to become further acculturated as well as take advantage of opportunities in his new adopted community, Schomburg took classes at night to learn English and during the day, he gave lessons in Spanish. Although he had been formally educated, he could provide no sufficient evidence; as such, he accepted a position as a messenger and clerk at Pryor, Mellis and Harris law firm. In 1906, he began working for the Bankers Trust Company, which soon promoted him to supervisor of the Caribbean and Latin American Mail Section. He continued to lead in this capacity until he retired from Bankers Trust Company in 1930.

As he supported himself and his family, he continued his quest in studying Africa Diaspora culture, specifically African-American and Caribbean history. In 1904, his article, “Is Hayti Decadent”, was published in The Unique Advertiser. Other writings, such as Placido, a Cuban Martyr, that discussed the life of Cuban revolutionary fighter Gabriel de la Concepcion Valdes, followed.

Schomburg studied historical persons of the Africa Diaspora, including Toussaint L’Overture, military leader of the Haitian Revolution; Frederick Douglass, orator, abolitionist, activist and diplomat; Chevalier de Saint-Georges, fencer, violinist virtuoso and composer; and Alexander Pushkin, the father of Russian contemporary literature who is considered to be the greatest poet in Russian history. He also learned of David Walker, a free man who authored and published the radical “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World” pamphlet; Phillis Wheatley, the first African American woman to have a book of poems published; Alexandre Dumas, pere, the author of such classics as The Three Musketeers, The Corsican Brothers, The Count of Monte Cristo; and Alexandre Dumas fils, the author whose work includes the romance novel, La Dame aux Camelias (The Lady of the Camellias), which Guiseppe Verdi adapted for his opera, La Traviate.

Schomburg discovered that the African heritage of many, including of Pushkin, the Dumas father and son; John James Audubon, the great naturalist, ornithologist and painter; and Ludwig van Beethoven, composer extraordinaire, had literally been whitewashed. Additionally, African Americans who held immense influence, like Paul Cuffee, were erased from history. Cuffee, a highly successful shipbuilder and maritime trader, was one of the wealthiest Black men, post-American Revolution. An advocate for the resettlement of freed African-Americans to Freetown in Africa, Cuffee was the predecessor of Marcus Garvey. Both men espoused Black pride, self-reliance and emigration to The Motherland. Schomburg would be inspired by Garvey, providing support to him; his publications, including Negro World, and his Black Star steamship line.

Arturo Schomburg often shared, discussed and even debated what he learned with many scholars, writers, artists and other Black professionals; quite a number of these individuals would be pivotal figures in The Harlem Renaissance. These individuals included W.E.B. DuBois, scholar, activist and the first African-American to earn his doctorate from Harvard University; Alain Locke, the first African-American Rhodes scholar and considered to be the Father of the Harlem Renaissance; and Aaron Douglas, an artist best known for his Migration series and the first African-American to exhibit in a New York gallery. Arturo Schomburg would leave an indelible impression on this explosion of African American cultural creativity, intellectual advancement and social immersion.

(No copyright infringement intended).

These exchanges inspired him to collaborate with his friend, John Edward Bruce, to establish, in 1911, the Negro Society for Historical Research. It supported African, African-American and West Indian scholars and their pursuits in learning. The society, according to Carole Boston Weatherford, who wrote in her children’s book, Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library, “…sponsored lectures and galas and, in its first year, amassed more than three hundred books and manuscripts. Arturo stored that collection at his home, alongside his own.”

In 1912, Arturo Schomburg and Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, an author who worked as an assistant librarian at the Library of Congress, coedited The Encyclopedia of the Colored Race. Two years later, Schomburg joined the American Negro Academy; he would also serve, as its fifth and final president, from 1920 until 1928. The American Negro Academy was founded in Washington, D.C. in 1897. It was the first African American society of activists, editors, educators and scholars that focused on classical studies, the arts, science and higher education in order to attain racial equality. In 1916, he published A Bibliographical Checklist of American Negro Poetry, the first bibliography of African-American poetry. Schomburg continued being active in various community organizations and, in 1918, was elected in his lodge to act as the grand secretary of the Prince Hall Grand Masonic Lodge of New York. He also acted as the treasurer for the Loyal Sons of Africa and was granted an honorary membership in the Men’s Business Club.

In 1925, Arturo Schomburg’s article, “The Negro Digs Up His Past”, was published in a special edition of Survey Graphic; this issue was in tribute to Harlem and its intellectual life. The dissemination and influence of this issue, especially Schomburg’s article, was massive; it prompted Locke to include it in his anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation. Historian and scholar, John Henrik Clarke, often relayed how Schomburg’s article greatly inspired him in, not only to connect with Schomburg but to guide him in learning Pan-African and Africana history.

John Henrik Clarke reflected on his first meeting with Arturo Schomburg in an interview with Civil Rights Journal, exclaiming that, “He was holding down the desk. I was a teenager then. So, I wanted to know the whole history of my people all over the world, henceforth, in the hour of his lunch hour! ‘Sit down, son,’ he said. ‘What you’re calling African history, Negro history, are the missing pages of World history. Read the history of the people who took you out of history, and you will find out why they were so insecure they had to take you out of history, why they could not stand for your history to compete with theirs.’ Once I began to have some background in European history, I could bring African history into proper focus.”

Arturo Schomburg was incredibly busy, between working; collecting materials; lecturing; writing; and building with various members of the organizations in which he was a member and those of the community. His private collection was gargantuan, long having outgrown the space in his family’s home.

Having created exhibits and lent personal materials to the New York Public Library, he was willing to sell his collection to the metropolitan library system. However, it lacked the funds to purchase the collection. The Carnegie Corporation purchased the entire lot for $10,000 ($145,000 in 2019) and, in 1926, gifted it to New York Public Library.

Schomburg’s collection was housed on the third floor of the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library system; it became the foundation of the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints. Located at 103 135th Street, in the heart of Harlem, that library was quickly grew into a hub of Black cultural and intellectual growth and activity. His collection, as Boston Weatherford detailed, “included more than five thousand books, several thousand pamphlets, plus priceless prints and papers – among them, an autographed first edition of poems by Phillis Wheatley, the brilliant slave girl. There were handwritten poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar, letters of heroic general Toussaint L’Overture, speeches of slave-turned-stateman Frederick Douglass, Benjamin Banneker’s early American Almanak, and a 1573 book of poems by Spaniard Juan Latino, perhaps the first printed book by a Black person.”

He would use part of the proceeds to travel throughout Europe, visiting England, France, Germany and Spain, undergoing further research about Africa Diaspora connections and influence. In 1927, the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints was opened to the public. In 1931, he was asked by administration at Fisk University, a historically Black university in Nashville, Tennessee, to found the Negro Collection at the academic institution’s library. He would acquire four thousand volumes, including The Lincoln Bible, which was given to President Abraham Lincoln by free Blacks from Baltimore during the Civil War.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Arturo Schomburg left Nashville and returned to Harlem in 1932. He traveled to the Caribbean that same year, taking the time to visit Cuba. Viewing himself as a connection between those in Harlem with those in Havana, he met with writers, scholars and artists who were proud of their rich cultural heritage. He later included the Cubans’ materials that he admired for the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints back in the States.

Having worked with the New York Public Library and the 135th Street branch librarian, Ernestine Rose, he accepted the offer to be the curator of the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints. He acted as the curator of his collection at this branch from 1932-1938. He also continued to speak publicly and write a weekly column, “Our Pioneers”, for the Amsterdam News, a Black-owned newspaper focused on the Black community in New York.

Arturo Schomburg guided researchers and acquired materials that supported his mission to learn and educate others about the vast accomplishments of persons of African descent. Two of his most valuable gifts were two classic bronze sculptures, African Venus and Said Abdallah, by sculptor Charles Henri Joseph Cordier. He collected works of Black artists and pieces that featured Black subjects, regardless of the artist’s race. His acquisition of art was diverse and the artists ranged from Harlem Renaissance painter Lois Mailou Jones to Spanish Baroque artist Juan de Pareja. Schomburg believed that art was of vital importance, as it could impact someone who may not read often or well.

On June 10, 1938, Arturo Schomburg passed away in Madison Park Hospital in the Brooklyn borough of New York City; he had fallen ill, post-dental surgery.

In 1940, the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints would be renamed the “Schomburg Collection for Negro History, Literature and Prints” by the New York Public Library. In 1972, the library system designated the collection as a research library; still located at 103 135th Street, it became known as the “Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture”. In 1980, a new Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture building opened at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue), between 135th and 136th Streets, in Harlem. It is around the corner from the original Schomburg Center.

While there are scholarships at Hampshire College and a fellowship at the University of Buffalo named in his honor, the legacy of Arturo Schomburg is immeasurable. Identified by Afrocentrist scholar, Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, as one of “100 Greatest African Americans”, Schomburg has been an inspiration for many of the Africa Diaspora, especially African Americans, Puerto Ricans and Latinx. In celebration of his dedication, Boston Weatherford concluded, “On his lifelong quest, he was not just collecting rarities; he was correcting history for generations to come. He wanted the facts to reach the community and boys and girls in classrooms to teach them that Black heritage knows no national boundaries. And today, the Harlem library bearing Schomburg’s name boasts more than ten million items, a beacon for scholars all over the world, bringing to light past glories that Arturo always knew existed.”

“…We need the historian and philosopher to give us with trenchant pen, the story of our forefathers, and let our soul and body, with phosphorescent light, brighten the chasm that separates us. We should cling to them just as blood is thicker than water.”

~ Arturo Schomburg