“Major Taylor … should be recognized as one of the pioneers in punching a hole through the walls of segregation that had stood ever since the Civil War. And he did it in the field of sports, a crucial venue for Middle America.”

~ Albert B. Southwick, retired chief editorial writer, Telegram & Gazette

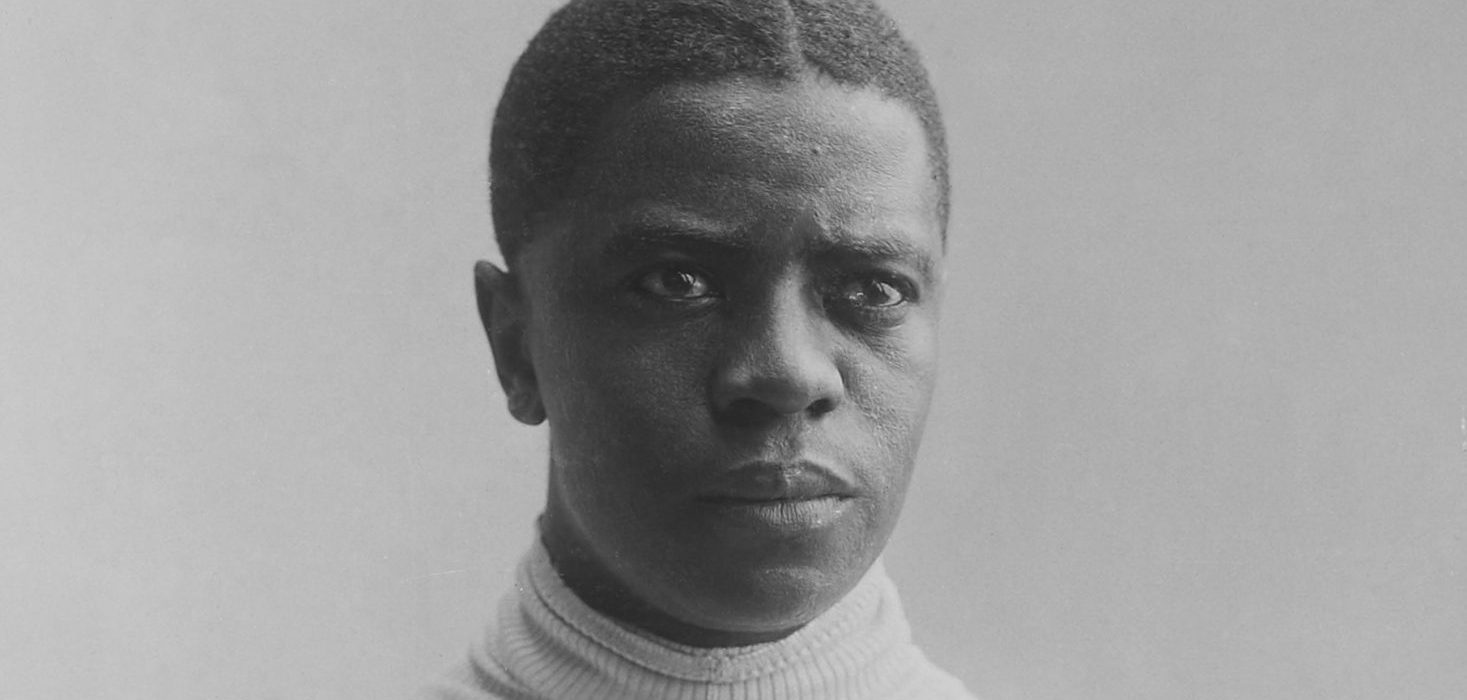

On November 28, 1878, in Indianapolis, Indiana, Marshall Walter Taylor was born to Gilbert and Saphronia ( née Kelter) Taylor; he would be one of three sons among the family’s eight children. Upon migrating from Louisville, Kentucky, Gilbert, a veteran of the Civil War, and his wife settled in a small Indiana community, Bucktown, a rural area west of Indianapolis.

By the time, Marshall was eight years old, his father began to work as a coachman for the Southard family, who were White and wealthy. Typical of many African-American men and their sons, Gilbert would, on occasion, have Marshall accompany him so the young boy could gain experience and knowledge. After a short while, Marshall became close with Daniel Southard, as they were the same age. When offered the possibility of Marshall living with the Southard family, the Taylors agreed because it offered advantages that, due to racial discrimination, were beyond those that the Taylor parents could provide. Those advantages were educational, economic and social and Marshall lived with the Southards for four years. When the Southards moved to Chicago, Illinois, Marshall resumed living with his family in Indianapolis.

One of the advantages the Southard family offered Marshall was a bicycle. By the time Taylor was fourteen years old, he had mastered performing tricks on his bicycle and Tom Hay, owner of the Hay and Willits Bicycle Shop, hired him to perform stunts in front of his store. In addition to performing stunts, Taylor cleaned inside the shop, earning six dollars per week and a new, expensive bicycle. It is believed that because he wore a soldier’s uniform when he performed his stunts that he earned the moniker of “Major”.

Taylor worked at the Hay and Willits Bicycle Shop for approximately one year, when he left in 1896 to work as a bicycle instructor in the downtown Indianapolis cycle shop of Harry T. Hearsey. After two years working at Hearsey’s shop, he met Louis D. “Birdie” Munger, who would have a significant impact on Taylor’s life. A former high-wheel bicycle racer, Munger owned the Munger Cycle Manufacturing Company, also in Indianapolis. Because of their passion for bicycles, Munger not only hired Taylor to train cyclists and promote his line of racing bicycles, but he became Taylor’s racing coach, mentor and lifelong friend.

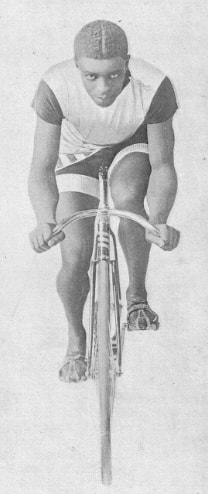

While Munger was training him to become a professional racer, Taylor, as an amateur, competed in track and road races. Excelling in track races, significantly the 1-mile (1.6 km) sprint, Taylor won his first cycling race in 1892. Given a fifty-minute handicap due to his young age (fourteen years old), he earned “First Place” in the 10-mile (16km) amateur event held in his hometown.

Major Taylor, the only rider to complete an intense 75-mile (121 km) road race near his hometown of Indianapolis, won his first significant cycling competition on June 30, 1895. As Taylor became more victorious and well-known, the greater racial discrimination, including threats and physical violence, he experienced. Munger and Taylor would often refrain from letting White racing officials and competitors know of Taylor’s entry in an event until the beginning of a race. Additionally, local track owners banned Taylor from competing, either because of their own racial prejudices, fear that other cyclists would not compete if Taylor was entered, or both.

Several days after winning, on July 4, 1895, he won a ten-mile (16 km) road race in Indianapolis. This win rendered him eligible to compete in Chicago at the national championships for Black cyclists. In that national championship, Taylor won the ten-mile championship race by ten lengths, setting a new record of 27:32.

In 1895, Taylor and Munger moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, which at the time, was the epicenter of the bicycle industry in the United States. Worcester, which contained half a dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops, was considered to be more accepting of others, regardless of race. The move east also, Taylor and Munger hoped, would lead to greater visibility, financial sponsorship and the ability to compete on a global scale. Munger and his business partner, Charles Boyd, established the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company with factories in Worcester, and Middletown, Connecticut. Taylor, who worked with Munger as a bicycle mechanic and messenger, joined the Albion Cycling Club, which was all-Black, and trained at the local branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Being a member of an all-Black cycling club was not new to Taylor, who had been a member of the See-Saw Cycling Club, which was formed by Black cyclists of Indianapolis.

The following year, Major Taylor won many races in his new home state as well as in Connecticut and New Jersey. One of those races that Taylor competed in was the “Derby of the East”, the 25-mile (40 km) Irvington–Millburn race in New Jersey. However, with less than half a mile (0.8 km) to cover in order to cross the finish line, Taylor was assaulted by someone throwing ice water into his face, causing him to finish the race in 23rd place. The first major East Coast race Taylor competed in was a one-mile (1.6 km) race sponsored by League of American Wheelman (LAW). Held in New Haven, Connecticut, Taylor began the race in the last place but won “First Place”. In August 1896, Taylor set a new unofficial new track record of 2:11 1⁄5 for a distance of one mile at the Capital City Velodrome; the official track record of 2:19 2⁄5 held by Walter Sanger, who was White. Some felt that Taylor was again discriminated against because he was Black; his being banned to race at the Capital City track did not deter speculations of prejudice shown towards Taylor. However, the official response to Taylor’s accomplishment not being accepted was that he could not officially compete against Sanger because Sanger was a professional and Taylor still held the rank of amateur.

In 1896, at just eighteen years old, Major Marshall Taylor turned professional. His first race was a .5-mile handicap that occurred on an indoor track at Madison Square Garden in New York City, December 5, 1896. The race, an opening day event, premiered in front of thousands of fans in attendance for a six-day racing event, held December 6–12. Taylor, who began the race with a 35-yard (32 m) advantage over the scratch racers, won the race. Riding a “Birdie Special” bicycle, made for him by Munger, Taylor resoundingly defeated his White competitors, including Tom Cooper of Michigan and E.C. Bald of New York.

The six-day cycling contest drew not only cyclists from across the United States but also from abroad. Cyclists, analysts and supporters from countries such as Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Scotland and Switzerland ascended on The City That Never Sleeps. Obviously, the massive international interest led to increased incentives for the cyclists, including a $5,000 prize for first place. This increase came as a detriment to the cyclists. Over the six days, many of cyclists, including Taylor, were exhausted, sleep-deprived and even suffered delusions and hallucinations. This event was the longest, most-grueling race in which Taylor had ever participated and on the final day of the long-distance race, he refused to continue to compete. Taylor completed a total of 1,732 miles (2,787 km) in 142 hours of racing, the estimated distance between New York City and Houston, Texas. He earned eighth place but would never compete in any other six-day race.

After Munger’s Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company went into receivership, Taylor began, in 1897, to compete on other racing teams. Consistently racing, Taylor experienced numerous wins, including, again, against Bald in a one-mile race in Reading, Pennsylvania. He finished in fourth place in the prestigious LAW convention held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

As a professional racer, Taylor constantly was the victor. He garnered the admiration of many, Black and White, including President Theodore Roosevelt, and was given thrilling names, such as “The Colored Cyclone” and “The Ebony Flyer”. However, he, as a Black cyclist, continued to suffer racism in the White-dominated sport. When the sport expanded to include areas in the American South, which was racially-segregated, local promoters barred Taylor from competing. Taylor returned to Massachusetts for the remainder of the 1897 season and Bald became the American sprint champion in 1897. Despite the pervasive obstacles of racism, Taylor was determined to compete.

By 1899, Major Taylor should have been named the national champion, as in his 1898–99 seasons, he established seven world records: the quarter-mile (.4 km), the one-third-mile (0.5 km), the half-mile (.8 km), the two-thirds-mile (1.1 km), the three-quarters-mile (1.2 km), the one-mile (1.6 km), and the two-mile (3.2 km) distances. His one-mile world record of 1:41 from a standing start stood for 28 years!

Unfortunately, the reasons for his not being awarded the 1898 championship title is said to be due to variations in scoring and “questionable” membership in the LAW. That year, Taylor and other cyclists left the LAW to join the American Racing Cyclists’ Union (ARCU) and its professional racing club, the National Cycling Association (NCA). Because the ARCU sprint championship finals were held on a Sunday, Taylor, who was a devout Christian, would not compete on the grounds of religious reasons. Taylor often read from his Bible and would pray before each race. The ARCU suspended his membership, to which he petitioned the LAW for reinstatement. The LAW accepted Taylor but the organization declared Tom Butler, who remained in LAW, as the league’s champion.

In 1899, Montreal, Canada, Taylor won the one-mile sprint, making him the first African-American to win a world championship in cycling. Taylor was the second Black athlete, after Canadian bantamweight boxer, George Dixon of Boston, to win a world championship in any sport. Taylor also placed second in the two-mile championship sprint and won the half-mile championship race. Again, the finals were held on Sundays and Taylor refused to compete for religious reasons. Taylor would not compete in another world championship contest until a decade later, in Copenhagen, Denmark. Because the LAW and the NCA organizations were rivals in 1899, Tom Cooper would be crowned champion for the NCA and Taylor would be crowned the champion for LAW.

The wins, literally, kept being attained by Taylor. Aside from being a world champion, he finished “First-Place” twenty-two times in major championship races throughout the United States. He regained the title of “The Fastest Man in the World” when he set a new world record of 1:19 at a speed of 45.56 mph (73.32 km/hr) for a one-mile (1.6 km) distance. This was possible because of intensive practice and the innovative design adaptations, including a lighter weight, longer gears, a chainless gear mechanism and a steam-powered pacing tandem, to Taylor’s bicycle.

By 1900, Taylor had to seek membership within ARCU & NCA, to whom he had to pay a five-hundred dollar fine, as LAW ceased governing professional cycle races. That year, he was to face one of his most bitter rivals, Tom Cooper. They would compete against each other in three heats at Madison Square Garden.

In his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds: An Autobiography, Taylor recalled the bigoted treatment of Cooper. He even recounted the language of Tom Eck, the manager of Cooper, during his exchange with Bob Ellingham. Eck’s derisively commented to Ellingham, Taylor’s manager, that “…Tom will now proceed to hand your little darkey the most artistic trimming of his young life … In this first heat, Tom is going to give the Major his first real lesson in the fine points of the French style of match racing. Tom has a fine assortment of brand-new tactics, fresh from Paris … However, Bob, I have cautioned Tom, in the best interest of the sport and for the good of all concerned, not to beat the little darkey too badly.”

The response of Ellingham was also included in the book. Ellingham asserted, “It is true … that Major Taylor has never raced in Paris and will, therefore, be obliged to ride this race on what he has been able to pick up on this side of the pond. What he may lack in track strategy, he will have to make up in gameness and speed. He is always willing to learn and never lets an opportunity slip by to teach the other fellow a point or two.”

In 1900, Major Taylor won the ARCU American sprint championship and soundly defeated Tom Cooper, the 1899 NCA champion, in a one-mile race held at Madison Square Garden. In front of 50,000 to 60,000 spectators, Taylor bested Taylor in two heats so overwhelmingly that there was no need to race a third. Taylor stated in his autobiography, “If ever a race was run for blood, this one was. Worldwide prestige went hand in hand with the victory. Neither Cooper nor Eck offered to shake hands with me at the close of the race, nor did they utter a word of congratulation. I have never seen a more humiliated pair of Toms than were Cooper and Eck as they marched silently to their dressing room.”

Taylor continued to set world records in the half-mile and two-thirds-mile sprints and even entertained with Charles “Mile-a-Minute” Murphy, as a vaudeville act, when he raced on rollers indoors in competitions with other riders. Around this time, he bought a stately home in Worcester.

From 1901-1904, Taylor traveled back and forth from the America to Europe and Australia. Just as in the United States and Canada, he worked hard and continued to be victorious. An example of his European success occurred in 1901, where he won forty-two of the fifty-seven races he entered. The following year, he won forty of the fifty-seven races he entered. With his global wins, came monetary gains, as his prize money in 1903 alone would equal approximately one million dollars in contemporary times.

(No copyright infringement intended).

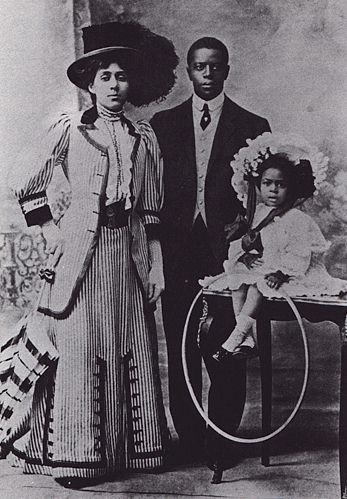

During this period, Major Taylor married Daisy Victoria Morris in Ansonia, Connecticut, on March 21, 1902. Morris was born on January 28, 1876, in Hudson, New York. The daughter of a single Black woman and an unidentified White man, Daisy was working as a servant and living with her aunt and uncle in Worcester when Taylor met her. In late spring 1904, in Australia, the Taylors welcomed their only child, a daughter that they named “Rita Sydney”. Her middle name was in honor of the city of Sydney, where she was born. When the Taylor family was not traveling, they lived in the home Taylor had previously purchased in Worcester.

Due to the extreme health and mental constraints that competing caused, Taylor refrained from racing for two and one-half years. When he returned to cycling, he set two world records for 1907 in Paris: the quarter-mile standing start at 0:25 2⁄5 and for the half-mile standing start at 0:42 1⁄5. Taylor returned to Europe to race in the 1908 and 1909 seasons, the latter in which he won his last professional race. On October 10, 1909, in Roanne, France, Taylor defeated French world champion, Charles Dupré.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1910, Major Taylor, after seventeen years of racing, retired; he was only thirty-two years old. Seven years later, he won his final competition, a race among former professional cyclists. He sought to attain higher education but without a diploma, he was denied entry into any institution of higher learning in which he was interested. Although he earned what is estimated in today’s currency as three – four million dollars (USD), Taylor was unsuccessful in several business ventures. Adding to his financial issues was his unwise investments and the stock market crash, which led to The Great Depression. To reconcile his debts, Taylor sold personal affects and property, including his home in Worcester.

In 1928, Taylor wrote and published, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds: An Autobiography. In it, Taylor expressed gratitude for his accomplishments and also acknowledged the inequity and destruction caused by racism, significantly from his personal experiences.

As Albert B. Southwick wrote in his article, “Much More than a Bicyclist”, the autobiography of Major Taylor, “… is a compendium of many of his victories. It is also a dismal chronicle of races lost because of dirty tricks White riders used against Taylor. They would crowd him off the track, hem him in ‘pockets’, rough him up off the field, curse and threaten him. There is no telling how often he heard the ‘N’ word, and other vicious epithets. After one close race (in Boston, no less!), a burly cyclist got him in a chokehold that made him black out before the police dragged the assailant off. In Atlanta, where he had planned to race, he was warned to get out of town in 48 hours or else. He finally gave up riding on the Southern circuit. He was refused hotel lodgings in St. Louis, San Francisco and other places. When the two big cycling organizations, the League of American Wheelmen and the American Cycle Racing Association got into a jurisdictional dispute, the ACRA tried to get him banished for life.”

Taylor personally sold his book and though he was a hero for many, significantly to Blacks, his sales never allowed him to earn above a meager amount on which he and his family could live. In 1930, Daisy took their daughter and moved to New York City. He would move to the predominately-Black community of Bronzeville in Chicago, never to see again the two.

In March 1932, Taylor suffered a heart attack and, after an unsuccessful operation, passed away on June 2; he was fifty-three years old. His wife and daughter, who survived him, were unaware of his death and no one claimed his remains. Initially, he was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in Greenwood Cemetery in Thornton Township near Chicago. In 1948, a group of former professional bicycle racers sought a memorial more befitting for someone one who accomplished so much, despite the tremendous adds against him. Utilizing funds gifted by Frank W. Schwinn, who owned the Schwinn Bicycle Company, the group organized and had Taylor reburied in a site worthy of the champion. The words engraved on the tomb’s plaque is truly worthy, author Paul Della Valle in his book, Massachusetts Troublemakers: Rebels, Reformers, and Radicals from the Bay State, recorded them: “World’s champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and God-fearing, clean-living gentlemanly athlete. A credit to his race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten.”

In more recent times, many tributes have been created in honoring the work and legacy of Major Marshall Taylor. These tributes include the Major Taylor Velodrome that was constructed in Indianapolis for their hosting of the 1982 U.S. Olympic Festival; the Major Taylor Cycloplex, also in Indianapolis; and the Major Taylor Cross Cup cyclo-cross. He has been, posthumously, inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame; awarded the USA Cycling Korbel Lifetime Achievement Award, the Massachusetts Hall of Black Achievement and the Hall of Fame of the Union Cycliste Internationale. In 2009, an Indiana state historical marker in honor of Taylor was installed in Indianapolis, where the Capital City track, where he had set an unofficial track record in 1896, once existed.

There are permanent monuments in Worcester, Taylor’s adopted hometown for 35 years and these include a boulevard named in his honor and a memorial. The 2008 opening ceremony for the memorial, included the premiere of an Antonio Tobias Mendez-designed bronze sculpture of Taylor surrounded by granite. An educational curriculum as well as a community mural led by Chicago artist Bernard Williams and a cycling trail in Chicago have been created on the life of Major Taylor. Perhaps the most enduring tribute to him would be the numerous cycling clubs named in honor of Major Taylor, the first organized in 1979 in Columbus, Ohio.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Major Taylor is also honored in popular culture, from being the topic in song, television and most notably, documentary. In 2018, the Hennessey brand of the luxury house, LVMH, released a commercial short, narrated by rapper, Nas, in their “Wild Rabbit” campaign, whose slogan is, “Never stop. Never settle.” It features Taylor racing in an indoor velodrome. In 2019, Hennessey sponsored the television documentary short, The Six Day Race: The Story of Marshall “Major” Taylor. Directed by Colin Barnicle, it features interviews with contemporary African-American cyclists and athletes, Ayesha McGowan and Nigel Sylvester.

“I pray they will carry on in spite of that dreadful monster, prejudice … and with patience, courage, fortitude and perseverance achieve success for themselves.”

~ Major Taylor